Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

First of three parts

Supporter Spotlight

Pamlico Sound is traversed each day by innumerable people aboard ferries, fishing boats and sailboats.

Most, however, probably don’t consider or are even aware of the intrepid explorers who first circumnavigated the vast estuary for the purposes of creating a map of the region and a visual record of the people who lived there.

It happened this month, 435 years ago, the second of Walter Raleigh’s three expeditions to establish an English colony on the North American continent.

At Ocracoke Inlet on Sunday, July 11, 1585, July 21 on our modern calendar, 60 men aboard four small boats “victualled for eight dayes” cast their lines from their mother ships and headed north to the mainland of today’s Hyde County. What lay ahead for the expedition was mostly unknown, terra incognita, both cartographically and historically. But upon their return from their portentous journey seven days later, cartography and history would be forever changed.

The general facts of the reconnaissance mission may be known to some readers while lesser known but consequential details within this article may come as a surprise to others. Among the more noteworthy achievements of the 1585 expedition is that it produced, according to the leading authority on the subject, “the most careful detailed piece of cartography for any part of North America to be made in the sixteenth century.”

Supporter Spotlight

Indeed, there was not another accurate map made of the shoreline of today’s Hyde County between the Pungo River and the Long Shoal River until the charts of the U.S. Coast Survey nearly 265 years later.

Of all the historians and writers who have told this story — mostly as a prelude to the alluring tale of The Lost Colony — none match the monumental academic achievements of the late David Beers Quinn, an Irish historian of “immense industry and erudition” who devoted his scholarly life to the subject of early English trans-Atlantic explorations. This writer had the good fortune to interview Quinn in 1984.

The praise of Quinn may be hardly sufficient. The comprehensive collection of contemporary records and historical analyses of those documents contained in his two volume colossal masterwork, “The Roanoke Voyages 1584-1590,” is extraordinary and unequaled. That is where we safely find the waypoints to retrace the 1585 circumnavigation of Pamlico Sound.

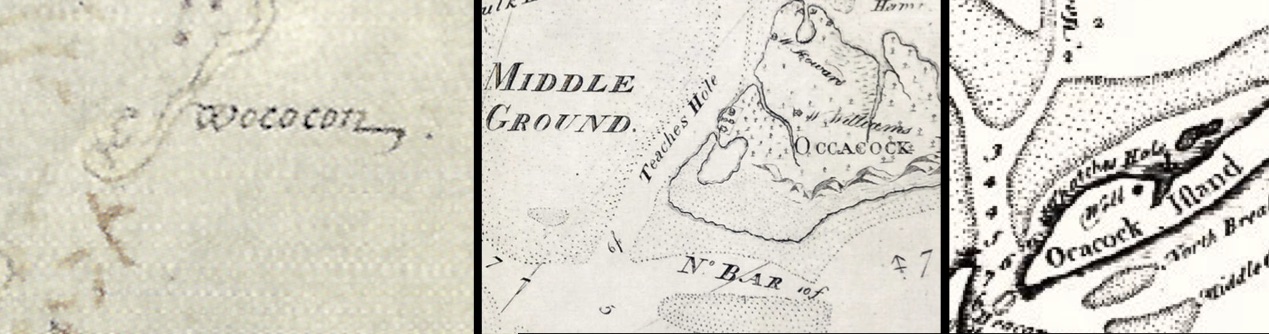

But Quinn, like all historians, was human, and although his mistakes were rare, one concerns his analysis of the location of the major Outer Banks passage through which the 1585 expedition entered Pamlico Sound and commenced their journey, then named Wococon Inlet.

Quinn and other notable historians following his trail have suggested that Wococon was a “now vanished inlet through Portsmouth Island.” However, two maps created in 1585, the “Virginea la Pars” and a more crudely drawn sketch map, depict Wococon Inlet with a conspicuous hook on the island’s southwestern extremity, which compares well with Jonathan Price’s rendering of Ocracoke Island and its inlet in 1795, 210 years later.

Furthermore, it may have been the freshwater well surviving to this day at Ocraocke’s Springer’s Point marked on Edward Moseley’s 1733 map, that attracted the Elizabethans to the inlet in the first place.

The 1585 expedition of seven ships was led by Raleigh’s cousin, 43-year-old Sir Richard Grenville, whose flagship Tiger grounded on the perplexing shallows of Ocracoke Inlet while making its way to a safe anchorage inside the bar.

Even though the accident was termed a “wreck” due to fears that the keel had been irreparably fractured, the badly leaking 160-ton galleon was re-floated, patched up and eventually was returned to England. While the ship’s carpenters turned to their arduous task of careening the ship and making repairs, and other sailors replenished the fleet’s water casks at the old well, Grenville and his officers decided to go on a tour of the adjacent sound.

The record of their itinerary strongly suggests that they knew where they were going. The excursion was provisioned for eight days, indicating that they had a reasonably good idea how far they had to travel.

According to the expedition’s journal, a week earlier Master John Arundell and the Croatoan Manteo had sailed to the mainland on an unspecified mission, likely to inform one or more of the towns of the larger group to follow, but that is only inferred.

Quinn also speculated that it was possible that Raleigh’s first expedition in 1584 led by captains Arthur Barlowe and Philip Amadas, with Manteo’s guidance, had reconnoitered some of the same shoreline of Pamlico Sound based on a remarkable story they were told of a shipwreck, likely Spanish, estimated to have occurred 26 or so years earlier on Wococon.

Native Americans related that “some of the dwellers of Sequotan” who were on Wococon perhaps gathering shells to make wampum, aided the shipwreck survivors. Had the estimated date of 1558 by the Secotans been slightly off, the shipwreck may have been one of the two Spanish “fragattas” lost in a storm off Core Banks during the 1561 expedition of Spanish Florida governor Ángel de Villafañe.

When the four boats departed Ocracoke Inlet, they contained a veritable who’s who of prominent Elizabethan captains, soldiers, scientists and surveyors. Aboard the lead vessel, a London tilt boat or ferry, was the red-haired Grenville beneath an awning to keep him out of the blistering July sun.

Ralph Lane, who would serve as governor of the colony on Roanoke Island in the coming year, rode in a ship’s pinnace of probably 30 feet in length that had been built at Puerto Rico to replace one that sank off Portugal on their way to the New World. Crowded among 20 or so others accompanying Lane was 25-year-old mathematician Thomas Harriot, the expedition scientist, ethnographer and Algonquian translator. Manteo likely sat near Harriot, excited to be triumphantly touring his land after a year in England.

Two smaller ship’s boats rounded out the flotilla, one carrying Capt. Philip Amadas, “admiral of Virginia,” the other including John White, the expedition surveyor and artist. Other scientific members of the party may have included a physician, a miner, and specialists in metallurgy, husbandry, apothecary and alchemy.

Harriot’s and White’s presence had the most lasting impact. Their collaboration produced a vivid visual and narrative record of the journey that rose to the quintessence of Elizabethan culture and science. Amadas’s contribution by the end of the circumnavigation, contrary to the expedition’s explicit instructions to treat the indigenous people of the Pamlico “with all humanitie, courtesie, and freedom so as to win them from paganism,” was no less than a haunting lesson of the capacity of English cruelty and the caprice of 16th-century Christian virtues.

The record does not reveal the weather conditions on that Sunday in July but from our own experience sailing on the Pamlico for many years we know the range of possibilities.

It may have been one of those sweltering “slick cam” days as they still say down on Core Sound, in which case the oarsmen suffered greatly; or the departure may have been delayed to wait for a strengthening afternoon sea breeze out of the southeast that would have sped them along on a starboard reach; or, more often than not in July, a blast furnace of wind out of the southwest may have filled their sails and tossed them across the sound’s notoriously short choppy waves. Summer thunderstorms and black squalls over the course of the week were surely encountered, delaying their progress.

While underway on a steamy day, the officers and the common sailors may not have been distinguishable by their clothing. Most were dressed in baggy, knee-length breeches or canvas Dutch-type slops and a loose-fitting woolen shirt with a wool monmouth cap atop their shaved heads despite the heat, to protect them from the sun.

The familiar accoutrements of a well-dressed Elizabethan nobleman— linen cartwheel ruffs with lace, elaborate doublets, leather jerkins, hose or legging s— were likely left behind, except for maybe Grenville, Lane and Amadas, who dressed in their finest prior to meeting their Algonquian hosts, including donning light corselets and swords.

In the event that the Elizabethans were not cordially welcomed, they also carried aboard the boats weapons, which included light muskets, swords, round or oval shields, long bows, half pikes and battleaxes.

Their first destination was the isolated town of Pomeiooc at the southeastern end of Lake Mattamuskeet, then called the great lake Paquippe. The course there took them about 20 miles across open water to the mainland and then 10 more miles along north shore of the sound, which looked much different than it does now.

Sandy hills and ridgelines later named Pungo Bluffs, probably remnants of an ancient oceanfront, were crowned by towering old growth forests shimmering on the horizon like a mirage from many miles out. Because the expedition journal indicates that they did not arrive at Pomeiooc until Monday, July 12, they must have spent their first night rafted together and anchored in a cove southwest of the village.

What must that have been like, 60 men crowded cheek by jowl in the small open boats on a relatively unknown shore at the mercy of the weather and fearsome creatures watching them in the dark? Surely they must have felt some apprehension, despite reassurances from Manteo that all would be well.

As they paralleled the mainland, it became Harriot’s and White’s task to triangulate the shoreline and adjacent islands as accurately as possible for a map, the map Quinn called “a landmark in the history of English cartography.”

Stowed aboard the four vessels were their tools of the trade: a cross staff, a sailing compass, an instrument for the variation of the compass, an instrument for the declination of the needle, watch-clocks “which dothe shewe & divide the howers by the minutes,” tables that calculated the trajectory of astronomical bodies, parchment for the production of “marckes” or sectional maps, and writing instruments of ink and lead.

As Quinn observed, when on shore the surveyors and their assistants were constantly attended by men carrying their writing materials, instruments, and plane tables on which Harriot and White drew bearings and distances on “paper royal” to compose their preliminary maps:

“The latitude of every ‘Notatious’ place was to be entered in the journal and on the map. A uniform scale was to be maintained at all costs. Distances of capes, headlands and hills, depth and breadth of inlets and rivers, elevations of land, with the variations in vegetation and land-use, location of springs, occurrence of shell-fish (especially those with pearls), and the various sorts of trees, were all to be entered both in the journal and on the map.”

In other words, the surveyors were thorough. We can closely scrutinize White’s watercolor map, “La Virginea Pars,” and find numerous geographic features that survive to this day, and by doing so we can go where they went 435 years ago.

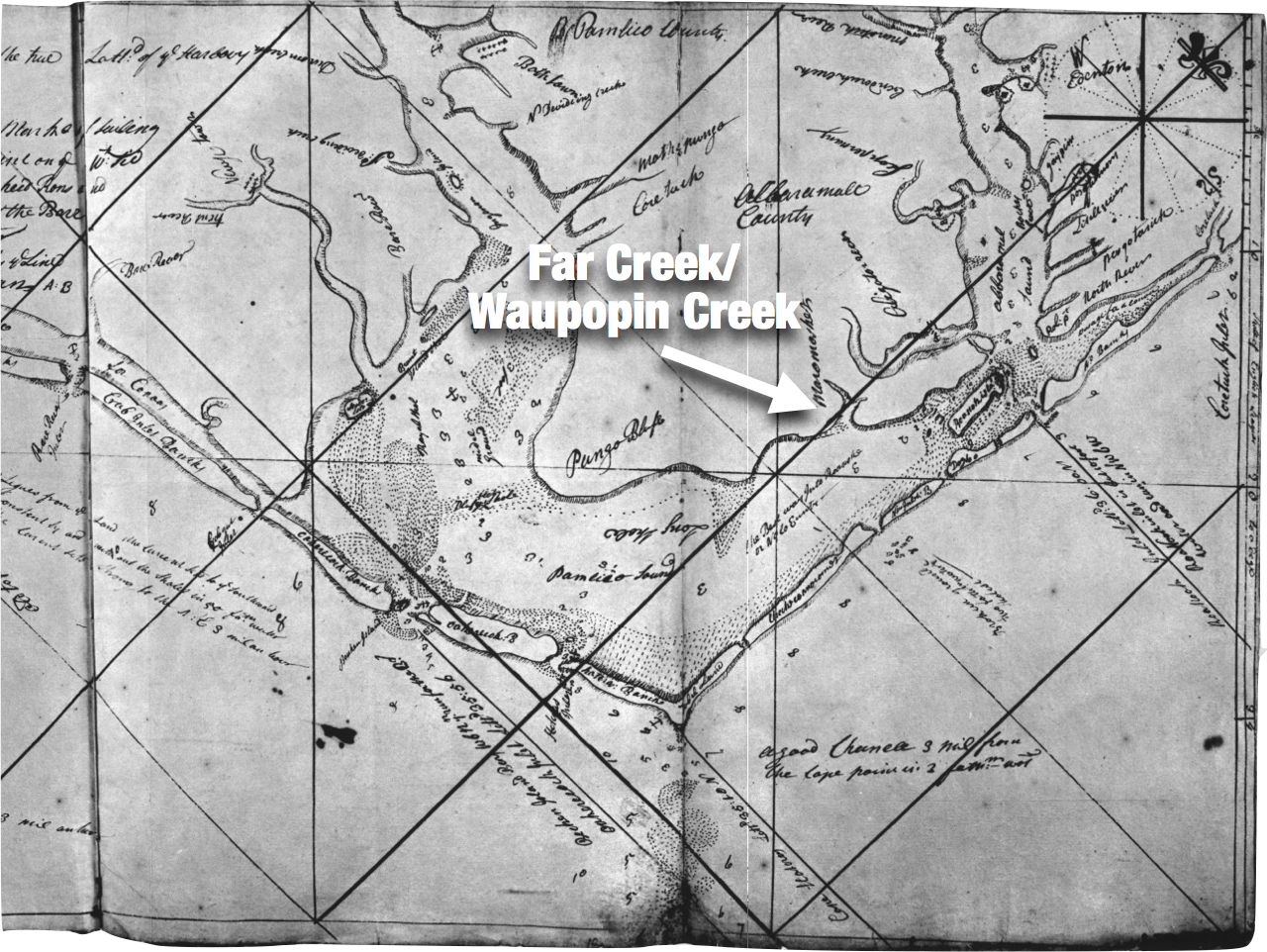

We begin retracing their route to the town of Pomeiooc, which was located close to the lake and west of a distinctive “Y” shaped bay. That bay is likely the similarly shaped branches of Far Creek and Waupopin Creek near Engelhard. This analysis disagrees with Quinn who thought it was Wysocking Bay where they landed to visit the village.

One hundred and fifty years after White drew them, albeit somewhat exaggerated in size, the same “Y’ shape of the two creeks appears on both James Wimble’s manuscript map of 1733 and his 1738 chart, although he mistakenly places the two creeks north of Long Shoal even though no similarly shaped creeks exist there today.

It was up today’s Far Creek where the Elizabethans rowed or sailed to find the remarkable palisaded town and its people.

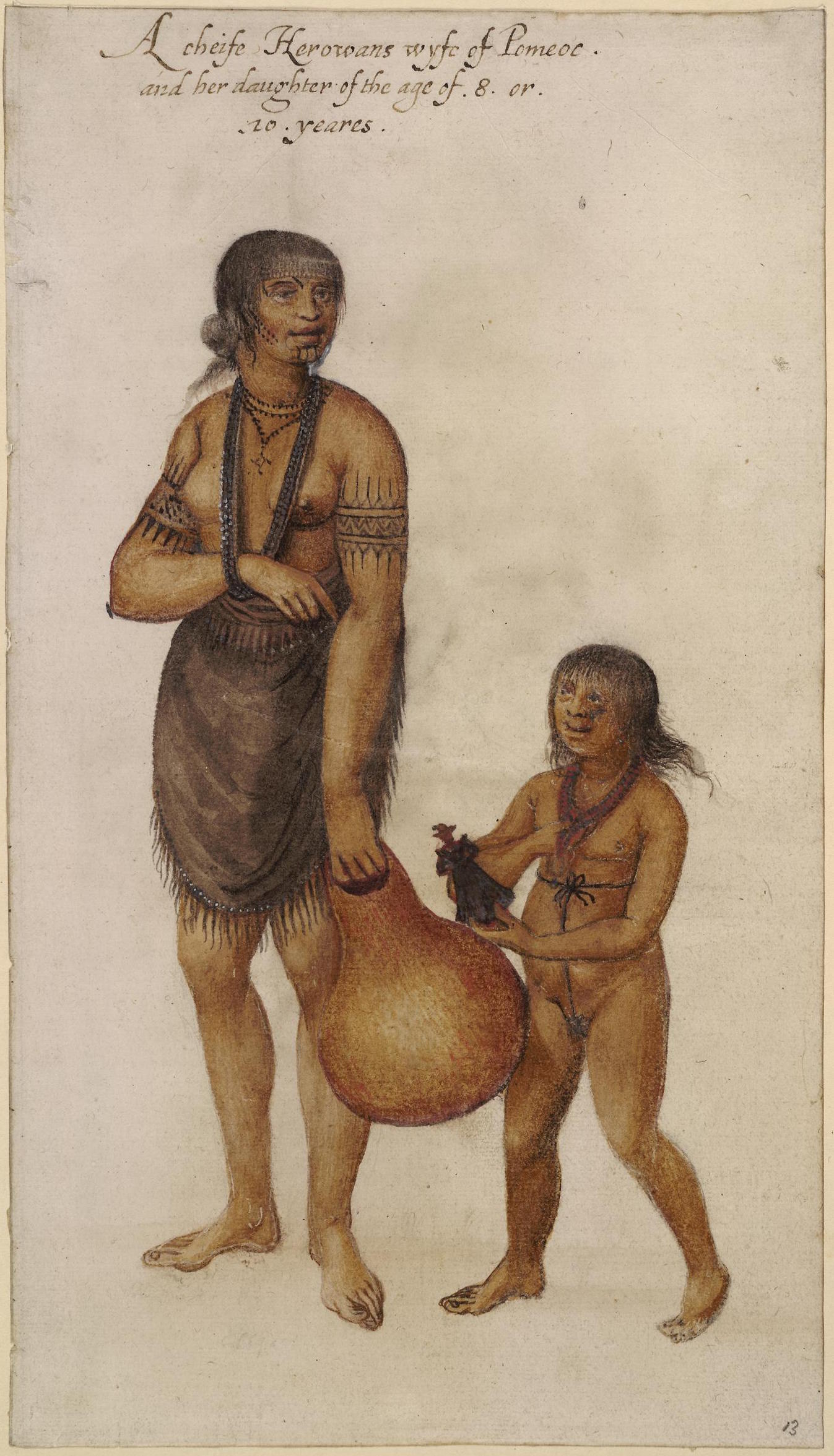

White wasted no time once they arrived, based on the product of his labors but unfortunately, we know nothing about the interaction and activities of Grenville, Lane, Amadas, Harriot and the other expedition officials, for the journal simply notes their arrival on July 12. Four illustrations were made by White in the span of a day including an extraordinary bird’s-eye view of 18 structures including individual homes, a temple and longhouses, one of which housed their “king” and his family.

The village was surrounded by a stockade fence, not to protect them from hostile enemies but to discourage the many large predators roaming the countryside including pumas, bears and wolves. Worth noting in the overhead view of the town was a man standing alongside a dog that was judged by Quinn as “the earliest appearance of this animal in an American drawing so far as is known.”

Manteo, no doubt, aided White in selecting and comforting his subjects about what the artist was doing. In addition to drawing a Pomeiooc woman carrying her child on her back, and a well-clothed village elder with hints of gray in his hair, White depicted the wife of the village chief with her 8- to 10-year old daughter, the “king’s” daughter, that reveals the only evidence of the presence or interaction between the English visitors and their host. The girl is holding a doll wearing Elizabethan clothing, perhaps representing Elizabeth I.

Without more information, we can only speculate how the tour of the village and surrounding land might have gone, partly based on similar instances of “foreigners” arriving for the first time at an indigenous village.

The children might have run from the strange-looking, wobbly-walking Elizabethans while the adults stood and stared. Manteo introduced the village “werowance” or chief to the sweaty, overdressed Grenville and his party, while Harriot and his assistants went off to view the great lake nearby. The guests were likely offered some food while both groups spoke pleasantries neither side could understand but nods and smiles were sufficient confirmation of friendship.

By the end of the day, Grenville and his party retired to their boats anchored on Far Creek, preferring to sleep on the water than experience the unknowns on shore. At the first blush of dawn the next morning, they headed west for the long journey to the towns of Aquascogoc and Secotan.