This story was updated May 8.

RALEIGH — If the federal government allows flexibility in use of the $300 million for the North Carolina Department of Transportation included in the General Assembly’s $1.6 billion pandemic relief bill approved Saturday, the cash-strapped agency will be able to respond to hurricane impacts.

Supporter Spotlight

Without access to the funds for anything that’s not virus-related, all bets are off.

“You’ll see barricades, and our crews go home,” state Transportation Secretary Eric Boyette said at the April 24 meeting of the NC First Commission, which was held remotely and streamed online.

The start of hurricane season June 1 puts new pressure on an agency already teetering on the financial edge.

Created in April 2019 to devise a long-term transportation investment strategy, the 14-member NC First Commission is now confronted with an emergency funding situation for the state’s roads, bridges, ferries, railroads and airports.

“The fear is, we’ve made obligations and we’re not going to be able to meet those obligations,” Boyette told the commission. “And that’s something this department has never done.”

Supporter Spotlight

Under the current scenario, with no funding help, he said, as much as 80% of the agency’s activities would cease.

“The only thing we could do is safety,” Boyette said. “We would try to keep everything safe for the traveling public.”

To illustrate the dire situation, a number of slides were shown of damaged culverts — one propped up with a pipe and others with rigged-together repairs from scrap wire and rebar — and undermined roads and bridges that had to be closed because repairs were not affordable.

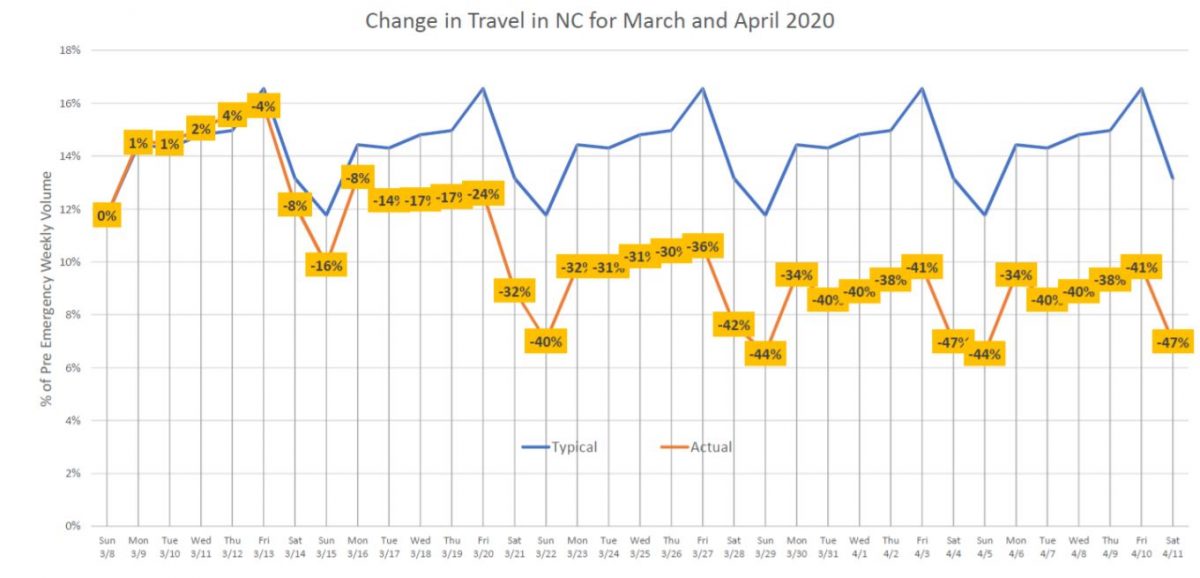

The additional loss of revenue from gas taxes and fees related to the COVID-19 restrictions have been a crushing blow to NCDOT, resulting in a loss of about $300 million this fiscal year, according to Boyette’s presentation. Traffic volumes plummeted 40 to 50% since the governor issued the stay-at-home order last month.

NCDOT is funded through the Motor Fuels Tax, which is currently about 36 cents per gallon, the Highway Use Tax and state Division of Motor Vehicle fees. Revenue shortfalls have caused delays in all but 50 major projects statewide, according to an NCDOT press release.

Whatever work that will be done is funded by grant anticipation revenue vehicles, or GARVEE bonds, BUILD NC bonds and federal grants. Deleted contracts include the controversial Mid-Currituck Bridge between the Currituck County mainland and the Outer Banks and the state Ferry Division passenger ferry from Hatteras Island to Ocracoke Island.

Victor Barbour, director of North Carolina government relations and highway-heavy division at Carolinas AGC, a construction trade association, said that the cuts have been “devastating” to the industry that works with NCDOT, from the engineers to the road builders to the material suppliers.

Barbour had retired in 2014 from NCDOT before accepting the position last year from Carolinas AGC. During his three decades with the agency, he was charged with design and construction of numerous projects, and helped develop the agency’s design-build program.

The situation for the department is bad from both sides of the aisle, he said.

“From the selfish perspective, it’s about the industry,” Barbour said. “From a public perspective, it’s about safety. I think as this continues on, that part of it will get worse.”

For example, if there’s no funding to do bridge maintenance, the concrete and metal will deteriorate and weaken. When delayed repairs are finally done, they will be much more expensive.

Barbour said that North Carolina had been known for the quality of its highway system, and it still is, but that reputation is starting to suffer.

“I think we’re better than most, but we’re headed in the wrong direction,” he said.

In 2018, he said, the department had about $3 billion in highway construction contracts. But in the next 12 months, there will only be $676 million in contracts.

The downturn is impacting “thousands” of jobs in the state, he said.

“That infrastructure spending helps drive our economy,” Barbour said.

What is needed, he said, is the $50 billion national infrastructure initiative that has been presented to Congress by an industry group. But meanwhile, the state has to find a way to restore NCDOT.

“There’s hard choices that have to be made,” Barbour said, “and they’re extremely difficult.”

NCDOT Assistant Director of Communications Jamie Kritizer said that even without the help of federal dollars, transportation workers would still be able to do some storm response.

“If a storm were to hit while we’re under the budget floor, we would have to respond using our own employees, equipment and supplies,” Kritzer said in an email. “We could not start any new contracts with outside vendors.”

Transportation maintenance projects have long been underfunded by the state, but NCDOT’s budget in recent years has suffered major hits from multiple storms and a court ruling that involves a large financial obligation.

According to a September 2019 financial review conducted for the department, its cash reserves had been depleted over the past year to the near minimum required by law over costs related to hurricanes Florence, Michael and Matthew, as well as response to snowstorms, rockslides and flash flooding. There were also high costs from the Map Act court case settlements and for projects that exceeded initial estimates.

One-third of the cash deficit, the review said, was attributed to the high number of natural disasters.

Boyette said it would take an infusion of $600-$700 million just to bring NCDOT financially back to where it was before the pandemic hit. It would take $1.34 billion “to be whole,” he added.

A temporary gas tax hike?

Michael Walden, a commission member and an economics professor at North Carolina State University, suggested that if the agency is in critical need of funding, it may be worth considering a temporary increase in gas taxes, which fund more than 50% of the transportation budget, while the price at the pump is so relatively low. Considering that gas is projected to cost only $2.21 a gallon in 2021, the public may be willing to tolerate a notoriously unpopular hike in the gas tax if it’s not permanent.

Walden told commissioners that he expected it will take a year or more for recovery of the state’s economy, which pre-COVID had relatively low inflation and rising wages.

“I think that makes this more difficult,” he said, “because it went from fairly good to fairly bad.”

In a later telephone interview, Walden, who at 70 has seen six recessions, said that the state is probably looking at losing about a third of its economy until it begins to grow again in the fall and winter. The good news, however, is that he did not expect North Carolina to suffer any loss of its brand, barring a huge spike in infections.

In the meantime, a 10- to 15-cent increase in the state’s gas tax could be a reasonable answer to keeping the lights on for NCDOT, he said.

“I understand that people don’t like paying the gas tax,” he said. But people also like good roads. “So, it’s a trade-off.”

Restrictions in travel and commerce, not to mention personal contacts and large gatherings, have had enormous consequences to local governments and small businesses. Tourism, one of the state’s largest revenue producers, has been crippled. Under such extremes, Walden said, government aid is not only appropriate, it is necessary.

“If you want to have an economy coming out of this, you’ve got to have some aid to sustain people through this,” he said. “The alternative is you don’t have half your economy.”

In time, Walden said, people will be driving all over North Carolina as much as ever because of its beautiful beaches and mountains, and tourism and business will come back.

But he warned against expecting a quick bounce back to normality.

“My brain tells me that people are going to stick their toe in the water and not go full fledge,” he said. “I hope I’m wrong, but my counsel would be: Be careful, be cautious.”