Today I am remembering a very special day just a couple months ago, before the quarantines and before the shuttered stores and empty streets, when Marion Evans and I explored a corner of the North Carolina coast that was completely new to me and seemed like an almost magical place.

Marion was my guide. She is a very talented local historian dedicated to discovering and preserving the story of the community where she grew up.

Supporter Spotlight

The community is called Piney Grove and it is is now part of Bolivia, a small town 15 miles from Southport, in Brunswick County.

Marion has been doing some extraordinary research on her great-great-grandfather and the founding of Piney Grove.

She and I had been talking on the telephone for some time about the community’s history, but I had never met her before or been to Piney Grove.

So when I was invited to give a lecture in Southport, I immediately called her up and asked if she might be willing to give me a tour of her part of Brunswick County while I was in the area.

She graciously agreed and we spent a lovely day together. I felt deeply privileged to learn about a part of the North Carolina coast that most people know only from quick glimpses as they speed down U.S. 17 on their way to Sunset Beach, Ocean Isle and Brunswick County’s other beach communities.

Supporter Spotlight

‘Old, Old, Old School’

Marion and I met in front of the county courthouse in Bolivia, which I find a strange and intriguing name for a town of 143 citizens built on a little rise of land between Half Hell Swamp and what is left of the Green Swamp, up in the headwaters of Lockwood’s Folly River.

Why Bolivia’s founders named the town after either the country in South America or the revolutionary for which it was named — Simón Bolívar, El Libertador — is a mystery.

Despite its small size, Bolivia is the county seat of Brunswick County, which is the coastal county that runs from the Cape Fear River, just below Wilmington, to the South Carolina border.

At the courthouse I jumped into Marion’s car and we immediately headed off to explore the countryside. Along the way, she regaled me with stories about Piney Grove, the old African American settlement where she grew up on the edge of Bolivia, down along Pinch Gut Creek.

Though still young in age and even younger at heart, Marion is already the caretaker of the community’s history and the keeper of its stories.

In a way she inherited that role from her grandmother, Goldie Evans. Much like Marion, she was the kind of woman that listened to the old people’s stories and remembered them.

Marion told me that her grandmother had 16 children, buried four, lived to be a 101 years old and never seemed to forget anything. She described her grandmother as “old, old, old school.”

I think I would have liked to know her. Marion said that she was a sweet, kind, funny and generous-hearted woman. She was also a local legend for always carrying a pistol in her purse and a rifle strapped over her shoulder.

Abraham Galloway’s Father and Mother

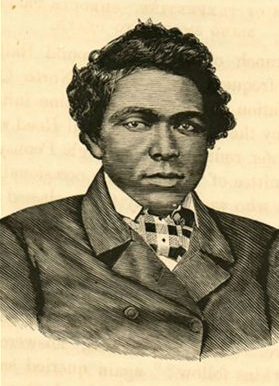

Marion began her tour of Piney Grove’s history on Galloway Road, which excited me because it led through the neighborhood that may well have been the childhood home of the father and mother of the young slave rebel Abraham Galloway, the hero of my book, “The Fire of Freedom.”

Abraham Galloway’s father had been a white ship’s pilot in Southport (not his owner), but he had been raised on a plantation on or close to what is now Galloway Road.

Abraham’s mother, Hester Hankins, was an enslaved African American woman. She too was likely born and raised in the vicinity of Galloway Road.

At a place I am sure I would not remember now, Marion turned off the road and drove up into a quiet glade where she showed me a large cemetery full of Galloways and Hankinses.

We got out of the car and walked among the headstones, under the bluest sky ever.

I imagined that somewhere near there, perhaps by unmarked graves along the tree line where slaves used to be buried, young Abraham Galloway had come and visited loved ones he had lost.

Piney Grove

As Marion and I drove up Galloway Road, we passed old farms, broad pastures and deep woods. Only once or twice did we see another vehicle on the road.

She told me that the road had always seemed like a special and enchanting place to her.

Everywhere we went, she pointed out interesting things: Piney Grove’s old farms, a pair of liquor stills in the woods, an unmarked graveyard — probably a slave cemetery — and the original site of the first St. John Baptist Church, which was built on Marion’s great-great-grandfather’s land, among many other sites.

The Seven Sisters

As we explored that far side of Bolivia, Marion also told me about the Seven Sisters. They were the Wilson family’s daughters, and she talked about them as if they still walked the Earth.

Almost 150 years ago, the Seven Sisters and their husbands and children founded Piney Grove. That was just after the Civil War, when that land was deep woods and turpentine camps.

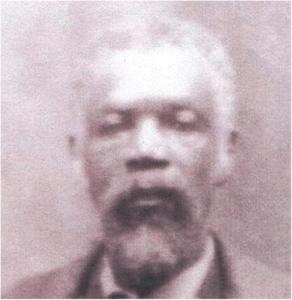

Marion’s great-great-grandfather, Caesar Evans, married one of the Wilson sisters.

Marion told me that a series of almost miraculous events had to happen to bring Caesar and her great-great-grandmother Annie together and, later, for Annie and Caesar to end up in Piney Grove.

First, Caesar managed to escape from the Evans family during the Civil War. The Evans family was from Greenville, in Pitt County, but it is not clear if Caesar escaped from their plantation there or from family lands in Brunswick County.

After taking his freedom, Caesar had to pass through untold dangers in order to reach the town of New Bern. The Union army had already captured the town and it had become an important refuge for fugitive slaves from all over eastern North Carolina.

In New Bern, Caesar enlisted in the Union army so that he could fight for his people’s freedom. According to Marion’s research, he enlisted in the 37th Regiment, United States Colored Troops, in 1864.

While serving in the Union army, Marion’s great-great-grandfather fought in the Battle of Fort Fisher, only a day’s journey from Bolivia.

Caesar Evans had barely turned 19 when he joined the Union army. But after the war, he returned to his old home and found his family again.

He was fortunate. Unlike so many other former slaves who tried to find loved ones after the war, Caesar Evans even located his mother Pleasant and his sister Delia, alive and well. Their owner had sold them away from the rest of the family in 1863, in the second year of the Civil War.

The more Marion spoke, the more I saw the countryside around me in a new way. The more she told me, the more I felt as if I could almost see the people in her stories come back to life.

Feeding the Alligators

We soon stopped at another cemetery and while we wandered among the gravestones Marion told me stories about the people buried there and also more about Caesar Evans and his family.

Only a few years after the Civil War, in 1869, Caesar Evans married Annie Wilson, and they settled down in the pinelands of Brunswick County.

They must have worked hard and been very frugal, because Marion discovered in old documents that Caesar purchased their family’s farmland in Piney Grove in 1881.

As we continued our journey, Marion and I passed the home where she grew up and the home of her charming mother, whom I had the privilege of meeting the next day in Southport.

Then we headed to Supply, a small town a few miles from Bolivia. On the way, we passed a creek where Marion’s school bus driver used to stop the bus and let the children feed the alligators.

Where the Coffles Rested

When we got to Supply, we passed through the little downtown and back into the country, and then Marion turned down a solitary dirt road that I never would have noticed if I hadn’t been with her.

A few hundred yards down the road, she stopped and we got out of the car again.

As she always does before going into the woods, Marion grabbed her hatchet in case, she said, wild critters or other varmints attacked her. Marion laughs all the time, but like her grandmama she does not play.

Hatchet in hand, she led me back into the woods to what was obviously a very old cabin built of logs and planks.

The planks in the cabin were cut uneven, by a sawmill that was not of this century or the last, and the logs that made up the walls looked ancient, though I don’t really know if they were as old as they looked.

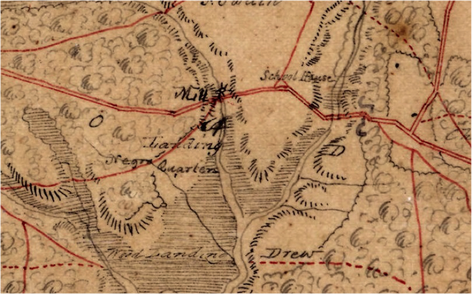

Marion told me that slave traders used to pass up and down the old King’s Highway, a Colonial road that was nearby.

That I did know. I had read many historical accounts that mentioned that road, and I had read descriptions of the chattels of chained men and women that slave traders used to drive up and down it.

She said that local legend held that the cabin had been one of the places where those slave traders and their coffles rested for the night when they were passing down the King’s Highway.

If the legend is true, I knew that most of those slave traders were taking their captives one of two places: either north to the slave market in Wilmington or south to the big slave market in Charleston, where roughly 160,000 Africans had first arrived in the U.S. in slave ships.

There in the woods, on the edge of that out-of-the-way little town, Marion and I imagined those people there in that cabin. Maybe they sometimes camped around the cabin too, because I have read historical accounts of slave coffles numbering in the hundreds, far too many for that cabin’s floor.

A Graveyard’s Ghost

Near the end of our day, Marion and I also searched in another stretch of woods, closer to Bolivia, for a graveyard that her grandmother Goldie Evans had often described to her.

Marion’s grandmother, who remembered everything and never exaggerated about anything, said that she had seen a ghost there one day when she was a child and walking home from school.

She was not the only one. Over the years, many others had seen the ghost, too.

The spirit, people said, was the ghost of a local white family’s son who died at Gettysburg.

Following her grandmother’s directions, we found the old cemetery in thick woods near the Old Ocean Highway.

Marion, of course, plunged right into the thicket, her hatchet at the ready, ghost or no ghost.

The Landing

When we came out of the woods again, Marion pointed up the road to a little bridge that crossed the Lockwood’s Folly River.

A long time ago, she said, boatmen poled flatboats up the river and came ashore at a little landing that was located near there.

The river is just a little stream by that point, but at the landing, enslaved men would load barrels of turpentine, rosin, tar and pitch.

On large plantations, often of thousands of acres, Brunswick County’s enslaved men and women used to make vast quantities of turpentine, rosin, tar and pitch. It was by far the county’s largest industry.

They made the turpentine and rosin by distilling the sticky resin of the local pine trees, and they made the tar and pitch by smoldering pine wood in earthen kilns.

After leaving the landing, the boatmen carried the barrels far downriver. They traveled until they reached the salt marshes near the river’s mouth and loaded them onto ships that carried them to sea.

‘A Great Wailing In the Community’

Marion told me a hundred stories. She took me to an incredible number of interesting places. And she taught me a tremendous amount.

We had a ball, too. Everywhere we went, we laughed a lot. But we also asked one another hard questions about the passage of time and how one comes to know a place and how we tell its stories.

As we headed back to Bolivia, we also stopped at her family’s cemetery, the Evans Cemetery, which is located in a copse of pines not far from the Friendship Church.

There we visited her great-great-grandfather’s grave:

CAESAR EVANS

Born 1846

Died

Jan. 8, 1928.

Gone but not forgotten

He died, Marion said, during a great thunderstorm, and when he breathed his last, the old people said that there was, and I quote Marion on this, “a great wailing in the community.”

Next to his final resting place, Marion’s great-great grandmother Annie is buried as well, and a host of Piney Grove’s other citizens, some recent, but others going back many generations.

We visited Marion’s grandmother’s grave, too, which was covered with beautiful red roses. Goldie Evans had passed away only a little more than a year ago, at the age of a 101.

She still carried her rifle on her back well up into her 90s.

As we stood there beneath the pines, Marion said that when she was young, if it was a Sunday morning, you could stand where we were in the graveyard and hear music all around you.

She said you’d hear gospel songs from two or three different churches rising above the fields and mixing with what the old folks called “devil music” that was coming from the revelers at a juke joint down the lane. I suppose the folks at the juke joint had been partying all night.

As she spoke, I could tell that Marion liked it all: the memories of all the saints and all the sinners, too.

She liked the graveyard where her people rested together. She relished the beauty of the fields, the creeks and the swamps where her ancestors had made a home.

She loved the stories that her grandmother and the rest of the old people had entrusted to her and she loved, no less, the memory of that music, the voices of the sacred and profane, all rising up to heaven.

Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.