The first of two parts

There’s a link between the growing problem of marine debris and challenges related to recycling, although folks don’t always make that connection.

Supporter Spotlight

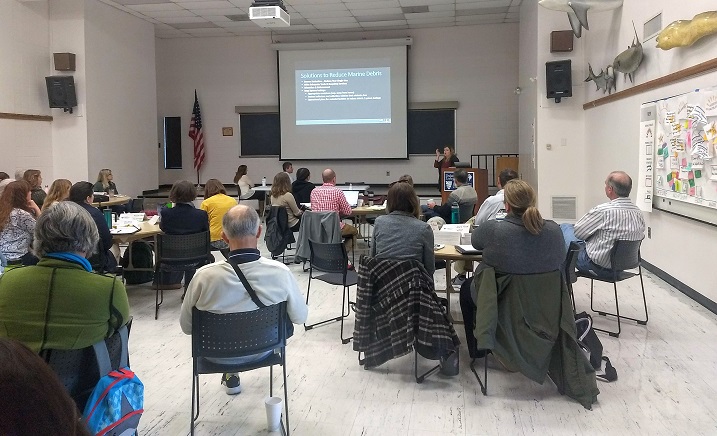

Wendy Worley, section chief for the Recycling and Materials Management Section, a part of the state Department of Environmental Quality, said recycling can effectively complement marine debris management. She made the case to attendees of the North Carolina Marine Debris Symposium held last month at Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort.

Symposium founder Lisa Rider, formerly with Onslow County Solid Waste, and now executive director of Coastal Carolina Riverwatch, said when she founded the Marine Debris Symposium eight years ago, it was difficult for marine scientists and others in the field to make the connection between solid waste and marine debris, which is why she incorporates into the symposium speakers from waste industry management and state programs.

Worley’s department is a nonregulatory division within DEQ that works to provide technical assistance and support for recycling waste reduction programs across the state. “Our office also provides economic development services to the recycling industry, growing existing recycling businesses and recruiting new businesses to the state to support and grow a sustainable, circular economy,” she said in an interview.

“Recycling is the most direct and easy way people can contribute to improving their personal environmental impact. Recycling delivers a host of environmental benefits, including saving energy, reducing dependence on landfill disposal, and conserving natural resources. In addition, recycling creates jobs and supports the local North Carolina economy,” Worley added.

Recycling helps with marine debris because it is an effective waste management tool. “By placing items correctly in the recycling container and ensuring they are not blown into the environment, you are ensuring that the material you produce is getting effectively returned into a valuable new product.”

Supporter Spotlight

Worley said during the symposium that marine debris can come from a range of sources, from people intentionally leaving garbage behind to unintentional littering.

The accidental littering is often caused by what she called system leakage, such as when waste unintentionally escapes from trash bins with unsecured lids or during the collection process, and this happens at both the domestic and international levels.

“China is a major contributor to the marine debris problem,” she said, as well as other countries.

The chart Worley used during her presentation states that based on 2010 data, China had 8.8 million metric tons of mismanaged plastic waste and of that around 3.53 million metric tons entered the ocean. In comparison, about 0.11 million metric tons of plastic marine debris is generated by the U.S. each year.

Worley acknowledged during her presentation it may feel overwhelming but, “I think that we can do something about that here locally just by managing our own materials in a more responsible way.”

Worley said ways to do that include reducing consumption of anything considered single use, such as plastic items and have an adequate trash and recycling service. Other methods she listed in her presentation to help reduce marine debris included providing education and enforcement, stopping system leakage, providing appropriate containers and having trained collectors and collection vehicles that minimize loss.

“If you don’t have anywhere to put the material or there’s not an efficient system to collect that material and get it to the appropriate location, then you end up with that leakage into the system,” she said, adding that cans, bottles and any kind of waste are going to “leak” into the environment. To help stop that leakage, it’s important to have appropriate containers with tight-fitting lids and containers available for people to use outside the home.

Beach communities can also take steps to better manage marine debris by putting solid waste infrastructure on beaches to make sure garbage doesn’t end up in the waterways, Rider told Coastal Review Online.

If a beach community has the capability to collect recycling, they are encouraged to implement a program, provide clearly labeled bins and make sure that trash cans and recycling bins placed on the beaches are emptied frequently and do not overflow.

The clearly and properly labeled bins are vital because, “When people are disposing of something it’s a decision that takes seconds … they need to know in seconds what to put in the bin” to help prevent contamination.

In Worley’s presentation, she points to contamination, or when nonrecyclable materials are introduced to the recycling mix, as being one of the biggest challenges for recycling.

Contamination is causing the cost of recycling to increase and it is often the result of confusing or incorrect information. Her department created the 10-week Recycle Right NC program that launched last fall to help educate the public about how to properly recycle.

Rider said that in North Carolina, “We’re really fortunate we have solid waste infrastructure and we have room for improvement and with recycling. As long as it ends up in a recycling or landfill facility, it’s great.”

She clarified that while many longtime recyclers consider landfills bad, not everything is recyclable.

“Without landfills where would it go? It would definitely end up in the ocean,” she said.

“There’s millions of dollars put into a landfill to make it as environmentally sound as possible,” she said, adding that landfills are heavily regulated and continuously monitored.

If a community doesn’t have the resources for recycling and waste collection, the focus should be on collecting what waste the community can collect to be disposed of in the right place before it enters the ocean, she said.

More importantly, Rider emphasized reducing consumption. “If you can buy something that’s reusable, there you go, it’s a no-brainer. Even if it’s more expensive, it will save you money in the long run,” she said. “Reduction, reuse and then repair. Recycling should be the last option.”

Rider said her passion for marine debris management began when she was 10, while participating in a cleanup with NC Big Sweep, a now-dissolved statewide program to clean up litter.

“I was hooked,” she said. “I did these cleanups for years and years.”

It was probably 2010 or 2012 when she found herself volunteering for five or six groups cleaning up the same locations.

“No one was talking to each other, no one was collecting data, I had this thought, why don’t we get together and talk,” she said.