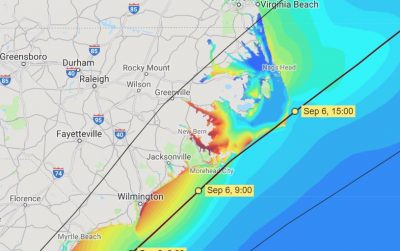

Storm surge is likely to be Dorian’s most dangerous and destructive force as the hurricane passes near or over the North Carolina coast Thursday night and into Friday.

A storm the size and strength of Dorian pushes an enormous amount of water around and as it makes an expected curve to the northeast, the impacts of that surge will vary widely with exactly where the storm tracks.

Supporter Spotlight

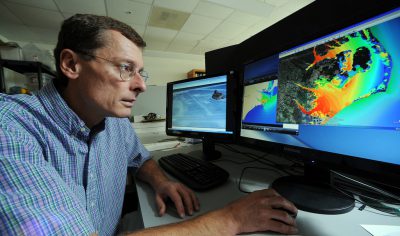

“Track location makes a huge difference,” said Richard Luettich, director of University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City and lead developer of predictive models of coastal storm surge that proved accurate in the last hurricane to hit North Carolina. One key, he said, is how the track interacts with Pamlico Sound, the largest lagoon on the East Coast.

“It’s a big shallow water body and shallow water is easier to pick up and lift onto the land,” Luettich said in an interview with Coastal Review Online. “It’s long, and long in the direction that the winds are going to be coming from.”

With hurricane-force winds extending 60 to 70 miles from the center of the storm, Dorian’s current track would create a powerful storm surge in the sound.

“What you’re going to see is an awful lot of water pushed from the northeastern part of Pamlico Sound into southwestern Pamlico Sound,” he said. “It’s likely to spill over into the land in Down East Carteret County and then push its way up the Neuse River as well.”

That means a high storm surge for towns along the lower Neuse River, including New Bern, which was heavily flooded during Hurricane Florence.

Supporter Spotlight

“New Bern kind of gets the brunt of it,” Luettich said. “As the river narrows down there’s kind of a funneling effect.”

Under the latest model runs, there will also be substantial beach erosion from high waves with the highest impacts likely to come along the strands just north of Wilmington, which could see the peak of the storm coincide with high tide.

“Storm tide, the combination of storm surge and high tide, will be maximum north of Cape Fear, in the Wrightsville Beach area, where the surge and high tide are likely to co-occur.”

A main worry in that area and especially along Topsail Island is that many of the dunes and beaches were heavily damaged in Hurricane Florence.

“That’s one of the challenges of having these (storms) year after year after year,” Luettich said “If the recovery isn’t fast then a much lesser event can cause as much or more damage in the follow-up year as a larger event would have with protective structure like a dune line intact and good and beefy.”

For now, Hurricane Dorian is expected to move along the coast much faster than Hurricane Florence, reducing the chances for heavy inland flooding. Its track resembles Hurricane Matthew, but for now it looks like it will follow much closer to the Outer Banks, which was spared much of Matthew’s wrath after the storm curved sharply out to sea at Cape Lookout.

Where Dorian tracks as it moves along the Outer Banks will determine the impacts. There’s a big difference in which side of that thin strip the storm is on.

Luettich said the more offshore the storm tracks, the more the main impacts are felt around Cedar Island, Portsmouth and Ocracoke.

If it tracks up the sound side, the impacts would be similar to Hurricane Irene, the 2011 storm that caused heavy soundside flooding on Hatteras Island and in soundside communities in Pamlico and Hyde counties.

In that scenario, as the storm arrives winds are blowing more east to west pushing water into Oriental, Hobucken, Bellhaven and Swan Quarter, Luettich said.

As happened during Irene, the sound side of Hatteras Island could even go dry, exposing the tidal flats. Then as the storm passes the winds blow west to east, pushing the water back and creating a storm surge on the back side of the barrier islands affecting Portsmouth, Ocracoke, Rodanthe and on up to Wanchese and Manteo. That dynamic, he said, is also the main source of new inlets.

“When you get inlets cut through a barrier island, it’s often the times you have sound water that gets pushed out to the coastal ocean,” Luettich said.