Reprinted from North Carolina Health News

North Carolina is not among seven states that will be awarded federal grant funding to conduct health studies on people in specific communities who have been drinking water contaminated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as PFAS.

Supporter Spotlight

The reason: North Carolina, which is said to have the third-worst PFAS contamination in the country, did not apply for a grant.

“It had nothing to do with someone dropping a ball at all in this case,” said Heather Stapleton, a researcher at Duke University whose work includes PFAS contamination.

Stapleton said she and a colleague had considered applying for one of the grants but realized they couldn’t meet enough of the criteria to submit a competitive application.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, or ATSDR, announced Monday that researchers in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, California, New Jersey, New York and Colorado will each receive $1 million to study the relationship between drinking water contaminated with PFAS and human health effects.

Little is known about the health effects caused by PFAS exposure, said Patrick Breysse, director of ATSDR and CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health.

Supporter Spotlight

“The multi-site study will advance the scientific evidence on the human health effects of PFAS and provide some answers to communities exposed to the contaminated drinking water,” Breysse said in a news release.

The exclusion of North Carolina from the grant money riles Emily Donovan, co-founder of Clean Cape Fear, a grassroots environmental group based in Wilmington.

“Our children were born drinking poisonous levels of PFAS tainted water,” Donovan said in a statement. “A quarter of a million residents downstream of DuPont/Chemours exposed us to dangerous levels of toxic PFAS for decades and our data will not be added to this nationwide study. It’s heartbreaking.

“Our participation in this study would have added valuable information to the nation’s understanding of human PFAS exposure.”

Who is responsible?

Clean Cape Fear says the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, or DHHS, was “ultimately responsible” for ensuring that the state applied for the grant. Donovan said the department should have been overseeing a roundtable group of health officials, research institutions and others to submit multiple grant applications. Other states did that, she said.

In response, Kelly Haight, a spokeswoman for DHHS, said the department searches for any opportunities to better understand PFAS exposures in North Carolina, including reviewing all potential grant applications.

“Although this particular grant was not appropriate to NCDHHS as a research study, NCDHHS did recently apply for another competitive CDC grant to better understand human exposure to PFAS across the state,” Haight said in an email. “Our application was scored highly by the reviewers, but unfortunately we did not receive funding.’’

Haight said DHHS also “works with academic researchers across the state to encourage and support them in applying for and conducting PFAS-related research.”

Chemours and GenX

An estimated 250,000 people who get their drinking water from the Cape Fear River downstream of the Chemours chemical plant in Bladen County have been exposed to high levels of GenX and other PFAS contaminants. DuPont, and later Chemours, had been discharging GenX into the Cape Fear River as a byproduct since 1980. New Hanover, Brunswick and Pender counties draw their drinking water from the lower reaches of the Cape Fear.

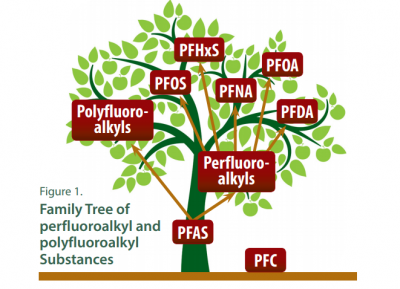

Levels of GenX, used to make Teflon and a multitude of other nonstick and rain-resistant products, are now well below the state’s health guideline, but residents wonder what the cumulative effects of the contamination are having on their health. An estimated 5,000 different PFAS are known to exist.

High levels of PFAS have also been found in the Haw River, which flows into Jordan Lake, where hundreds of thousands of people get their drinking water.

Four new PFAS found

Last year, results from a study conducted by N.C. State University’s Center for Human Health and the Environment revealed four newly identified PFAS in the blood of the vast majority of the Wilmington residents sampled. The study participants got their water from the Cape Fear Public Utilities Authority.

The study also found that participants had twice the national average of perfluorooctane sulfonate — or PFOS — in their blood and three times as much perfluorooctanoic acid — or PFOA. Those two legacy compounds have been phased out because of concerns about the environment and human health.

The two compounds are often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down easily in the environment. GenX and other PFAS with shorter carbon chains replaced them. The study found no detectable levels of GenX in participants’ blood.

According to Clean Cape Fear, there are no health-effects data for the newly identified PFAS found in people who participated in the study — Nafion byproduct 2, PFO4DA, PFO5DoDA, and Hydro-EVE.

“It’s reasonable to assume residents in New Hanover, Pender, and Brunswick Counties who regularly consumed tap water sourced from the Cape Fear River during the height of our contamination story have varying levels of these newly identified PFAS in their blood,” the statement says. “Yet, residents are unable to manage the potential health risks associated with these exposures because no health data is available to help medical practitioners preemptively screen and/or address potential health problems for their patients.”

Dr. Kyle Horton, a member of Clean Cape Fear’s leadership team, said the grant funding would have provided an “invaluable shot to advance our understanding of the links between PFAS exposure and important health endpoints like kidney function, thyroid disease, liver disease, lipid metabolism, diabetes, and immune and vaccine response.”

State should act

The organization is now calling on North Carolina leadership to address the emerging threat of PFAS water contamination on human health at the state level.

“NC needs to fund their own parallel or similar study asap,” Clean Cape Fear said in the statement. “Our NCGA lawmakers need to stop playing partisan politics and draft a budget that includes grant money to fund our own statewide PFAS Human Exposure study. People down here are suffering and dying. We deserve a fighting chance to address our own health needs and that starts with knowing what this crap does to our bodies.”

Last year, the General Assembly allocated slightly more than $5 million to the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory to study PFAS contamination in the state. The collaboratory has made grants to researchers at seven state universities.

Among many other things, those researchers are now sampling all public drinking water supplies in the state for PFAS.

Additionally, N.C. State announced in May that North Carolina, Michigan and Colorado will receive a $1.96 million grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to work collaboratively on research to determine whether limiting PFAS in public drinking water is enough to protect human health.

The contamination is also showing up in locally grown food.

This story is provided courtesy of North Carolina Health News, a website covering health and environmental news in North Carolina. Coastal Review Online is partnering with North Carolina Health News to provide readers with more environmental and lifestyle stories of interest about our coast.