For nearly as long as scientists have been sounding alarms about rising seas, they’ve warned that North Carolina’s long Atlantic coastline and vast network of estuarine waters makes its coastal property especially vulnerable.

But even after recent years of extreme flooding, construction along North Carolina’s beaches has continued apace, with many homes built within the last decade in high-risk areas, according to a new analysis from nonprofit science group Climate Central and national real estate data company Zillow Research.

Supporter Spotlight

The report, released July 31, updates the 2018 “Ocean at the Door: New Homes and the Rising Sea,” that projected impacts of average annual ocean flooding on coastal property. It now also looks at 10-year flood risks and incorporates fuller home footprint data.

Rising seas are expected to cause severe flooding that happens an average of every 10 years – or a 10% annual risk – to reach farther inland. Such floods can damage or destroy structures and interior furniture, create unhealthy mold, rust out vehicles and destroy dunes, pools and landscapes.

Estimates in the report were based mostly on data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and from Zillow. Risk levels created by rising seas will be influenced by the level of action taken by governments to alleviate carbon emissions by 2050 and 2100, as well as varying elevations and the effectiveness of flood controls, the report states.

Zillow does not take a position on public policy or real estate regulations, said Sarah Mikhitarian, senior economist at Zillow. But she said that accurate information about sea level rise risk is necessary in making decisions about protecting and enjoying real estate.

“I think that it’s something homeowners should be aware of, and future buyers as well,” she said. “Without intervention, thousands of coastal homes will experience increased flooding.

Supporter Spotlight

“We definitely wanted to shed light on the impact climate change could have on the industry and people.”

The report revealed that in a third of all 24 coastal states and the District of Columbia, the rate of new construction – after 2009 and before 2017 – has been faster in 10-year flood risk zones than in non-risk zones. At least 17,800 homes built in the last decade will be at risk of inundation of a 10-year flood by 2050, according to the report. By 2100, the risk is projected to be two times higher – or as much as three times higher if nothing is done to stem carbon pollution.

A total of about 10,500 new homes stand on land that will be within the annual flood zone by 2050 – about 7,000 fewer than those that will be in the 10-year flood zone.

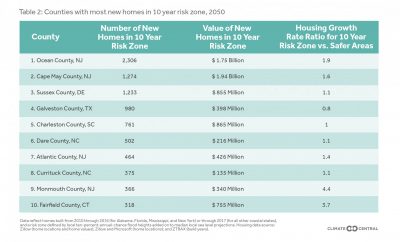

Of the 37 counties nationwide with more than 100 homes built in at-risk zones after 2009, two of the top 10 are in North Carolina: Dare County, ranked sixth, with 502 houses; and Currituck County, ranked eighth, with 375 houses.

Overall, North Carolina ranks second among states with the highest number of new homes built in the 10-year flood risk zone during the last decade, with 1,910 homes valued at a total of $840 million. The number of new homes built statewide in the annual risk zone over that same period was ranked second, behind New Jersey, with 1,231 houses totaling $543 million in value.

Although no cities in North Carolina were ranked among those with more than 100 new home in areas of future 10-year flood risk, the nearby cities of Norfolk, Virginia, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, and Charleston, South Carolina, were ranked in the top ten.

Even as dire as some flooding scenarios could be, the current data does not include deluges that many coastal areas have been experiencing lately, often separate from tropical storms and nor’easters.

“It does not account for rain,” said Climate Central spokesman Peter Gerald.

Gerald said scientific models can accurately predict tidal flooding from water bodies but flooding from heavy rainfall is still difficult to model.

Other variables, such as the recent extreme ice melt in Greenland, could also change the degree of flooding. Gerald said the report does consider the contribution of glacial melt in Antarctica, as well as the potential that less impact could result from more remedial action.

“Panic doesn’t help. Planning does.”

Peter Gerald, Climate Central

Like Zillow, Climate Central does not advocate for policy, Gerald said. It is seeking to provide information that can help homeowners and prospective buyers assess their risk and take the proper measures if appropriate.

“This isn’t doom and gloom and trying to scare everybody into panic,” he said. “Panic doesn’t help. Planning does.”

By 2050, Dare County is expected to have 11,689 houses, valued at more than $4.8 billion, affected by flooding, according to information provided by Zillow Research. By 2100, the number would rise to 18,808 houses valued at $7.69 billion.

Dare would also have the most new houses affected in the state. By 2050, 502 houses worth $2.1 million would be in 10-year flood zones and by 2100, there would be 786 houses worth $3.8 million.

Flooding in New Hanover County would cause the second highest impact in the state. By 2050, there would be 4,316 houses valued at $2.9 billion in 10-year flood zones and by 2100 there would be 8,107 houses valued at $5.6 billion.

Carteret County, on the other hand, had the biggest jump in homes affected. From 5,369 valued at $1.9 billion in 2050 to 11,631 houses valued at $3.8 billion in 2100.

Risk is part of the calculation when choosing where to live, but with so many climate threats – tornadoes, wildfires, hurricanes, volcanoes, earthquakes, heat waves, drought – people may discount the likelihood of future risks, especially when they’re 80 years out, and focus on near-future rewards, Mikhitarian said.

Choosing a home is to some extent an emotional decision, she said, and much goes into weighing multiple factors, including children and grandchildren enjoying a house in decades to come.

“People love the water,” she said. “A lot of people hope for the best. “

But homebuyers and owners, she said, need to “bake” flood risk into a list of things they need to consider in assessing the safety of the home’s location.

“It’s important for people to realize what could happen, “ she said.

With coastal real estate and homebuilding industries such a huge part of North Carolina’s tax base – as well as the tourism ecosystem – lawmakers and policy makers in North Carolina have been reluctant to discourage, or regulate, coastal development. Until recently, the state barely acknowledged that rising seas endanger coastal infrastructure, environments and lifestyles.

But as Mikhitarian sees it, the industry operates responsibly within the state’s regulatory framework, while walking a tightrope between climate threats and the housing market.

“From the real estate industry perspective, people continue to demand and want to live on that part of the coast . . . because they value the ocean so much.

“I think what puts the real estate industry in a tough position is it’s profitable to build coastal homes because there’s a demand for it,” Mikhitarian said. “And you can’t really fault them for that.”