Process to Better Manage Pollution Could Take Years

RALEIGH — Shortly after noon on July 10, the Lower Cape Fear River ceased to be classified as swamp water.

The action came during the windup of the state’s Environmental Management Commission’s monthly meeting in the Archdale Building on North Salisbury Street and it ends a regulatory saga with as many twists and turns as the Cape Fear River itself.

Supporter Spotlight

At the terminus of the journey is the same predicament as when it started: Starved for oxygen, the Lower Cape Fear River is a highly impaired waterway loaded by industrial and municipal discharges and agricultural runoff. At the same time, it’s the main drinking water source in one of the fastest-growing regions of the country.

The swamp water status, in place for about four years, was rejected outright by environmental groups as a way around tighter environmental regulation that conditions in the river required. Last year, after an official review, the Environmental Protection Agency said the state had failed to prove as required that the classification was the result of natural conditions. In a brief two-page letter rejecting the reclassification and parts of the state’s current management plan, EPA officials said there was no documentation provided to support the swamp water classification.

Last week, officials with the state Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Water Resource said, in light of the repeal of the swamp water rules and the current management plan’s flaws, the next step should be development of a completely new management plan.

The commission obliged and directed the division to develop a new plan for the Lower Cape Fear River Basin.

As the follow-up to the decision last week, the Division of Water Resources is expected to formally request the official rule changes during the Environmental Management Commission’s meeting in September.

Supporter Spotlight

DEQ officials said Wednesday that division staff would be meeting soon to work on the next steps in developing the new management strategy. Officials estimated it could take a year or more to complete the science needed to begin developing a plan. The regulatory framework will take longer as will the public review process and an automatic review of any rules that result by the legislature.

As lengthy and complex a process as that’s likely to be, advocates say it is a long-needed reality check.

Will Hendrick, senior attorney with the Waterkeeper Alliance, one of the groups that petitioned the Environmental Management Commission to drop the swamp water classification, said developing a new management plan is an opportunity to take a larger look at the river basin.

“From my perspective, the opportunity that DWR now has is to take a more holistic view about what is causing the problems that it needs to address in the Lower Cape Fear,” he told Coastal Review Online in a recent interview. “The biggest problem with the existing management plan is that it exclusively looked at permitted, point sources and it exclusively looked at new and expanding permits. It didn’t look at who was currently operating, and it didn’t look at non-point source pollution.”

Hendrick said that means taking a serious look at the effect of upstream nonpoint contributors, primarily large-scale animal operations.

“It’s a big and complex system and unless you’re going to look at all the sources then you’re not going to have any chance of solving it. What I hope is that they will meaningfully evaluate all the contributors to the in-stream conditions and not try to hide the ball.”

Brooks Rainey Pearson, the attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center on the reclassification petition, agreed that a new plan has to include an assessment of the impact of sources upstream.

“We’ll be looking for a plan that includes all sources contributing to the pollution including upstream non-point sources.”

Brooks Rainey Pearson, Southern Environmental Law Center

“We’ll be looking for a plan that includes all sources contributing to the pollution including upstream non-point sources,” she said.

A new management plan could take two to three years to go through the rulemaking process. Complicating the process is how rapidly the areas around the river are changing and a new federal designation that will require additional review.

In August 2017, the National Marine Fisheries Service designated the Lower Cape Fear River as a critical habitat for the endangered Atlantic sturgeon.

Rainey Pearson said that designation will require the Division of Water Resources to craft a management plan that will meet dissolved oxygen levels required to sustain the sturgeon nurseries.

Hendrick said the division will also have to take into consideration the lack of information about the fast-growing poultry industry and its effects on the watershed.

Unlike new hog operations, poultry farmers are not prevented from building in the 100-year floodplain, he said, adding that the state needs to get a better understanding of the size, scope and impact of the growing number of poultry operation in the Cape Fear River basin.

“We don’t have a good monitoring system for poultry,” Hendrick said.

The Long and Winding ‘No’

Although it involved all the complexities of the state rulemaking process and a federal review, for those who have fought the designation, the story of how the river became a swamp is an example of convenience over science.

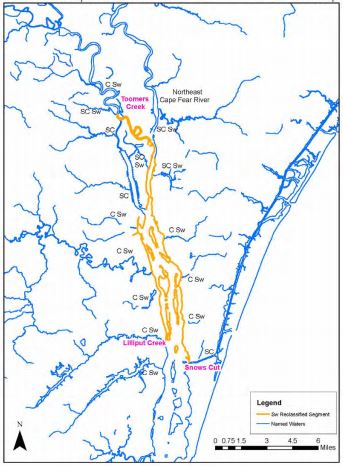

In spring 2014, the Cape Fear River Program, representing a group of industries and local governments with discharge permits for the river, sought to reclassify the 15-mile tidal, saltwater section from Toomers Creek near Leland to Snows Cut near the Atlantic Ocean from Class SC waters to SW swamp water designation, which would allow for a lower level of dissolved oxygen.

Class SC waters are all tidal saltwater bodies that are protected for recreation such as fishing, boating and other activities involving minimal skin contact; fish and noncommercial shellfish consumption; aquatic life propagation and survival; and wildlife, according to DEQ. The SW classification covers waters that have low velocities and other natural characteristics different from adjacent streams.

The request worked its way through the state review system before reaching the Environmental Management Commission, which approved the change in September 2015 in the face of objections from environmental groups that called the action a thinly disguised attempt to get around regulations.

“The definition of swamp water was inconsistent with the in-stream conditions.”

Will Hendrick, Waterkeeper Alliance

The issue also drew the attention of legislators, prompting an attempt by Rep. Billy Richardson, D-Cumberland, to reverse the new rule. The bill failed to get a committee hearing, but Richardson was able to make his case on the House floor when he offered it as an amendment. He called the swamp water classification “intellectually dishonest.”

The beginning of the end of the swamp water designation came last year after the EPA’s official review that found the state had no data, specifically anything on stream velocity, to back up its assertion that the stretch of river at issue was a slow-moving swamp.

In reality, Hendrick said, the Cape Fear is a fast-flowing river and in the 15-mile stretch that was reclassified it’s likely flowing quickly enough to suppress some of the nutrient retention.

“The definition of swamp water was inconsistent with the in-stream conditions,” Hendrick said, “and the EPA pointed that out.”