MOREHEAD CITY – Charles “Pete” Peterson, who retired June 30 as distinguished professor at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences, credits his time as a graduate student at the University of California Santa Barbara for his combination of passionate environmental activism and rigorous, world-renowned marine research.

It wasn’t, Peterson said last week, his parents’ idea of a suitable academic path for someone who’d earned his undergraduate degree in biology at Princeton University in 1968.

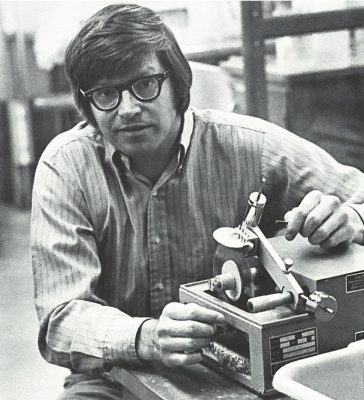

Supporter Spotlight

Princeton, after all, was and still is an elite, private Ivy League school.

UCSB?

“I had trouble telling my parents,” Peterson recalled about a week after his retirement after 43 years at UNC-Chapel Hill and its marine science laboratory in Morehead City. “It wasn’t UCLA (University of California Los Angeles) or Southern Cal (University of Southern California),” which were the flagship schools of the California system. “It was known as a ‘surfing school.’”

But it turned out to be the right place at the right time. In 1969, the year before Peterson earned his master’s degree in biology with a minor in oceanography at UCSB, picturesque coastal Santa Barbara was the site of what was, until the Exxon Valdez spilled 11 million gallons of crude off the coast of Alaska in 1989, the largest oil spill in the nation’s history.

The Santa Barbara spill spewed an estimated 3 million gallons of crude oil into the Pacific, creating a 35-mile-long oil slick and killing thousands of fish, sea mammals and birds. It was a disaster of epic scale. But for a budding young marine scientist, the tragedy was also inspiration and a research opportunity. Fifty years later, Peterson clearly remembers volunteering in a Santa Barbara city park to help clean up and save oil-coated, poisoned seabirds.

Supporter Spotlight

“It was an assembly line,” he recalled. “It was sad. But we did the best we could.”

Twenty-four years later, in 1993, after earning his master’s and doctoral degrees in biology and a post-doctoral degree in zoology at UCSB and teaching, doing research and publishing papers at the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and UNC-IMS, Peterson began a 21-year stint on the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council, advising its director on the effectiveness of restoration efforts and reviewing research proposals.

One of his key roles, he said, was convincing the council that long-term research into oil spills’ effects was essential. It wasn’t, he said, “about just cleaning up and moving on,” because what happened in Alaska would surely be applicable to future spills. An article he wrote in the journal Science made waves in the understanding of ecosystem-wide damage after oil spills.

In 2010 when the Deepwater Horizon disaster broke the Exxon Valdez record, with 210 million gallons spilled, Peterson was the lead author in a report on a study produced by the Gulf Oil Spill Ecotox Working Group at UCSB’s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis and published in the journal Bioscience.

In an article about the report, published in UCSB’s The Current, he was quoted as saying, “We now have a sense that the bulk of the impact was probably in the mid-water and deep ocean. “Who the heck knows what oil does to the mid-water pelagic and deep-dwelling critters? We need an integrated collaboration between deep water explorers, modelers, ecotoxicologists, microbial ecologists, and so on — all working together in unprecedented ways. We need a whole new type of marine ecology.”

Seashells on the Jersey Shore

Peterson came to all of this naturally. He grew up on a barrier island on the New Jersey shore, and at maybe 5 or 6, he said, became enamored with collecting seashells. With the inquisitive mind of a scientist-to-be, he asked his parents a lot of questions about them. They bought him some books.

The interest in marine organisms stayed with him — he’s still fascinated by shells and has gone to see numerous collections. The fascination set him on a career path, knowingly or not. In high school, he received an award from the National Science Foundation that enabled him to spend a summer studying coastal ecology at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California.

He studied and he surfed. And, Peterson says now, he knew then that California was where he needed to be.

When he arrived at UCSB, he was, he said, just plain lucky. His adviser was Joseph Connell, an ecologist and expert on biodiversity, coral reefs and rainforests. The grad student soaked it all up.

He researched the damage from oil spills to marshes and marine organisms, and when it came time to get a job, Connell and a famous professor at Princeton, Robert McArthur, had connections and influence. McArthur was an ecologist who had made significant contributions in many areas of community and population ecology.

“It’s funny,” Peterson said. “You sometimes make decisions that you don’t really understand, that don’t seem to make sense to some other people at the time, but you meet people who end up helping you. You just never know.”

Peterson interviewed for positions at a number of California schools, including Stanford, UC-Davis and Cal State-Fullerton. But by then, he said, he was a bit tired of the unbearable California traffic and ready for change. So, he went to the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and loved it.

He got to do research in the vast Chesapeake Bay system, traveling into Virginia as well as Maryland. And, crucially, UMD-BC had connections to UNC, where professors were doing research in North Carolina’s vast estuaries, including the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds.

When it came time to move on – “You have to provide for your family, and I’d gotten to that point,” he said – North Carolina and UNC beckoned.

Part of the reason, he said, was that even back then, UNC’s marine science program was interdisciplinary with professors teaching about and researching a wide variety of subjects. UNC also had a marine lab in Morehead City, and it had a focus not just on academics for its own sake but also on applying research to solve problems in the region.

Peterson certainly did that.

He was on the state Environmental Management Commission, a policy-making panel, from 1989 until 2013 and was deeply involved in formulating the state’s first stormwater rules to protect coastal water quality by limiting the amount of polluted runoff into creeks, rivers and sounds. He fought hard battles there and has never been convinced the rules were or are now strong enough but believes they’ve helped.

“We had to do something,” he said. At the time, in the early 1990s, there was almost no rules to stop runoff from entering coastal waters, carrying pollutants from streets, parking lots and rooftops. Shellfish harvest closures were increasing rapidly, and nitrogen and phosphorous were causing ever-increasing algal blooms, which rob waters of oxygen.

That effort, he said, was “facilitated” by the then-very-young North Carolina Coastal Federation and its founder-director, Todd Miller, whom Peterson said had “a great ability to communicate with people” and make compromises, rather than alienating potential allies.

Peterson also served for years on the state Marine Fisheries Commission, an often-controversial panel that makes policy and rules for the state Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Marine Fisheries. He became known as a fighter for the region’s commercial fishermen, but one who based decisions on science instead of emotion.

Peterson developed long-lasting relationships with state government decision-makers and with environmentalists. He was outspoken but couched his comments in science.

Peterson’s research helped lead to stronger standards for the sand that is placed on the ocean strand during beach renourishment projects. He had noticed that some sand was either too shelly and not beach-goer friendly or smothered marine organisms, such as mole crabs, that live in and near the surf zone.

“I didn’t come out against beach nourishment,” he said, because he realized the value of a wide beach to the coastal town’s economies. “But I did try the best I could to make sure that nourishment would be the best we could do.”

In recent years, Peterson has pushed hard, publicly, for rejuvenation of the state’s oyster population, which a few decades ago was devastated by habitat losses and a parasitic disease known as dermo that kills oysters before they reach harvestable size. But it’s not just been a push for economic reasons, it’s also been a push for water quality, because oysters are filter feeders and remove pollutants.

Some of his recent research focused on oyster reef ecology, work that has been used by the state and the Coastal Federation in developing new reefs in the Pamlico Sound, funded by the North Carolina General Assembly. Research by Peterson and others at UNC has also shown that a combination of oyster reefs with the planting of sea grasses, a living shoreline, is a viable, cheaper and often more effective form of erosion control than seawalls that also creates habitat for other marine species.

Peterson is pleased about the restoration projects and that living shorelines are gaining favor.

“I’m happy to have played a part in these things,” he said.

Peterson has also supported wind energy development and believes it’s a viable alternative to offshore oil drilling in many places, including North Carolina. He’s disappointed that little has come to fruition, so far, and recalls that not so long ago, the state was a leader.

Science-Based Policy

For his work and his dedication to environmental education in other arenas, Peterson in 2007 received the federation’s Pelican Award for outstanding government service. He said he was proud to receive it, but also proud that he got it without compromising principles of applying science honestly to affect policy.

“I have never,” he said, “advocated for something I didn’t believe was not based on scientific evidence.”

Throughout his career, Peterson’s been known as an effective, even enjoyable, communicator of science to the masses. In interviews with reporters and public talks, he avoids scientific names for marine organisms, sometimes calling ’em “critters,” as he did in the interview about the Deepwater Horizon study. Or he’ll call them “cute,” or “cuddly.”

He believes scientists should not only emerge from the ivory towers, they should “talk to people in ways they can understand” how research and policies affect them.

Peterson said that he and others at UNC-IMS have worked with public school teachers to develop basic lesson plans so students can appreciate and understand the marine environment.

He’s also worked with his students to make sure that when they speak to the media, government officials or regular folk, the message can be easily understood and recognized as important.

Peterson’s students, he said, will be his most important legacy. He’s proud that many he trained have been successful and dedicated to science and the public application of research. He’s most proud, perhaps, that many were women because his goal for years has been to narrow the gender gap in his field.

“I love it when they move on” to UNC and other schools and make significant marks in the field, he said. And he’s particularly happy when they contribute to their communities by serving on committees and working with interest groups to preserve marine habitat.

“That’s what it is really about,” he said. “It’s about teaching. It’s really what has always driven me. You can do all the research, all the other things. But what really matters is passing it on to the students.”

Peterson loves, he says, seeing the spark of passion arise in a student, that indicator that there’s a desire not only to learn, but to make a difference.

So, what’s next for Peterson?

He said he still adjusting to “this retirement thing,” but he isn’t sitting back and doing nothing. He’s long had an interest in sea turtles, he’s been associated for years with the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, on Florida’s Gulf Coast. He plans to spend more time there now, with an eye toward helping turtles and other marine mammals by working to help shape policies.

He might move to Florida, after decades of living on Bogue Sound in Pine Knoll Shores, where he helped raise a family. The Sarasota area is famous for shell collecting, which, after all, is kind of where this whole journey began decades ago in New Jersey. But Peterson said he won’t abandon North Carolina, or stop being involved in what he believes is important to the state’s marine environment.

“It’s been home for all these years, and it’s important to me,” he said. “I might be a little less involved, but I’ll weigh in when and where I think I can help make a difference.”