Reprinted from North Carolina Health News

After a decades-long absence, large-scale algae blooms have for the past four years returned in parts of the Chowan River, Edenton Bay, Albemarle Sound and Little River, and counties are looking to the state for help.

Supporter Spotlight

On July 5, the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality, Division of Water Resources reissued a warning to the public to avoid contact with green or blue water in the Albemarle Sound and adjoining water bodies in the far northeastern regions of the state.

State officials with the N.C. Division of Water Resources continue to urge the public to avoid contact with green or blue water in the Albemarle Sound and adjoining waterbodies, due to an algal bloom that has lingered in the area since May 14, 2019. https://t.co/H0MiCuqj06 pic.twitter.com/85FJWPXl9u

— N.C. DEQ (@NCDEQ) July 5, 2019

Another harmful algae bloom had been reported that same day, in Dances Bay on Little River, the next in a series of alerts that have been issued throughout the spring and into the summer.

Algae blooms have lingered in the area since May 14 and have been observed in parts of the Perquimans, Pasquotank and Chowan rivers.

The algae contributing to the blooms are cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, some species of which can produce harmful toxins called cyanotoxins.

Supporter Spotlight

State health officials are encouraging the public to avoid contact with large accumulations of algae and asking the public to prevent children and pets from swimming or ingesting water in an algal bloom. Counties affected so far include Bertie, Chowan, Pasquotank and Perquimans.

More recently, on Tuesday, state Department of Health and Human Services officials released a report urging the public to stay out of the east side of Chowan River, near Arrowhead Beach, north of Edenton. A bloom of cyanobacteria, after about a week of monitoring, was producing the toxin microcystin at levels officials consider “a high risk for acute health effects during recreational exposure.”

“Environmental conditions controlling toxin production by cyanobacteria are not well understood and can change rapidly over time and location,” according to the report, which advised people in the area, especially those with children and pets, to avoid the water, wash with soap after any contact and not to handle dead fish from affected waters.

Since their return in 2015, these annual summer blooms in and around the sound have triggered advisories for swimming and eating fish. Researchers agree 2015 had the worst blooms seen in the sound since the late 1970s, and 2019 is continuing a pattern of blooms starting earlier, before the heat of the summer creates the prime conditions for blooms to occur.

But researchers aren’t sure why.

How blooms burst

Blooms thrive on warm temperatures, sunlight and nutrient-rich waters. The sources of blooms often narrow down to two culprits: nitrogen and phosphorus. These enter waterways through stormwater runoff, which carries them from lawns, roads, septic systems and agricultural fields.

Hans Paerl is an aquatic microbial ecologist at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City. Paerl said these excess nutrient inputs are precursors to blooms.

“A bloom, in simple terms, means excessive growth of algae to the point when you can almost see it, and it’s a visible phenomena because of the high biomass of organisms in the water,” Paerl said. “So in order to generate that much biomass you need sufficient nutrients.

“Human nutrient over-enrichment has been identified as pretty much the basic cause of blooms.”

Wet winters and springs, followed by warm summers with droughts and stagnant water, combine with increased nutrient inputs to create the perfect storm for the maximum bloom, Paerl explained.

“That’s pretty much the formula,” said Paerl who’s been studying blooms in North Carolina and around the world for more than 40 years. “That’s the formula for them to dominate the system and that is what’s happening in the Chowan and Albemarle.”

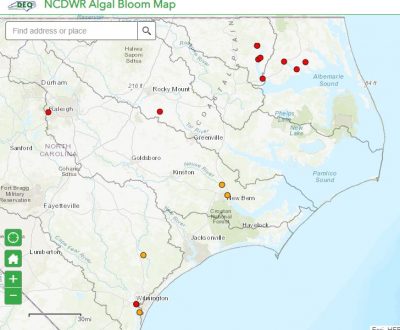

Identifying nutrient hot spots and sources is the key to combating algal blooms. Staff from the state Division of Water Resources regularly monitor and map elevated algal densities and blooms.

The division’s interactive map of state blooms recorded six cyanobacteria blooms in the Albemarle in May and June and two more in July.

Sarah Young Perkins at the Division of Water Resources said follow-up monitoring of blooms depends on staff time, the bloom types and the public’s use of the water bodies. Priority is granted to water bodies that are used heavily for recreation and affected by cyanobacterial blooms, but she said frequent monitoring is difficult because of staff limitations and the tendency for blooms to migrate and dissipate rapidly.

Wary Communities

Cyanobacteria blooms are easy to spot. They usually appear bright green, or milky blue when they start to decay. The cyanotoxins they can produce can be hazardous to human health.

Paerl said DEQ has done a good job alerting the public on blooms and their hazards, but he still worries about human exposure to pathogens from fish kills caused by low-oxygen conditions in the water.

“There’s a variety of issues that would make one be very leery about swimming, for example, in affected water, and for sure ingesting anything from those waters, including catching fish,” said Paerl, who noted shellfish also present risks.

Mark Powell, a consultant for the Albemarle Resource Conservation and Development Council, or ARC&D Council, said there is no shortage of local concern about the blooms.

“When people go out and use the water for recreation — pulling inner tubes with kids — people want to know if the water is safe to swim in,” Powell said.

“Our general rule is if the water is green, just don’t get in it.”

Mike Ervin has seen a lot of blooms in his lifetime. Ervin, director of the Edenton Historical Commission, has lived in the area on and off since 1962. He’s aware of the dangers but not too concerned.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cyanotoxins affect the nervous system, and symptoms of exposure can vary from skin irritation to neurological problems. The effects vary depending on exposure, whether through skin contact, inhalation or ingestion, as well as duration and the specific cyanotoxin involved.

“I’ve swam in it many a time,” Ervin said. “You come out green, you come out with it attached to you, but I’ve never seen people go to the emergency room and say, well I’ve been swimming in the water. I’m not saying it doesn’t happen but I’m saying I’ve never seen it.”

He said the warnings have more to do with making sure people err on the safe side.

There’s no automatic reporting of any adverse health effects from an algae bloom to the state Department of Health and Human Services. When the department does get reports, they get passed along to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to the division, thus far, no human or animal illnesses have been attributed to harmful algae blooms in the state. Cyanotoxins have never caused a human death in the United States but have caused the deaths of pets, livestock and other wildlife, according to the CDC.

From blooms and back again

Ervin said he hasn’t seen any bad blooms this year, and the blooms so far have been quickly dispersed by wave action and wind movement. But he noted some years are worse than others.

“I can remember back in the ’70s and even into the early ’80s the entire river was green,” Ervin said. “I mean it was nasty.”

Paerl began his work in North Carolina in 1978. The first big project he worked on was figuring out how to control blooms in the Albemarle.

“They were having pretty large blooms like they’re having now that were causing problems,” Paerl said. “Not only this issue of surface scum but also toxicity associated with the blooms.”

As for the cause, Ervin singled out a fertilizer plant in the Hertford County town of Winton that dispersed phosphates into the river.

“You know a lot of places make the proclamation that the algae blooms were caused by hog waste runoff and fertilizer runoff, but we’ve never had that in this area until actually the fertilizer plant was built,” Ervin said. “And then those phosphates ran into the water, and of course they eventually had to close that plant.”

Paerl said their study at the time also concluded phosphorus inputs, and to some extent nitrogen inputs, entering the river had to be reduced.

“After we made that recommendation and the state put a tighter noose on phosphorus inputs coming into the system, sure enough, the blooms abated,” Pearl said. “We can all pat ourselves on the back for having come up with the right formula for controlling the blooms, but lo and behold, 20 to 25 years later we’re now back into a bloom situation on the Chowan.”

The 2015 blooms on the Chowan river and Albemarle sound were extensive, Powell said, and blooms have occurred in varying degrees, duration and locations in the area of the sound every summer since.

“When the algae blooms popped up again in 2015, after an absence of 30, 35 years, it was a real shock to everybody,” Powell said. “Because we hadn’t seen them for a long time and we thought the water quality was pretty good.”

Paerl, Ervin and Powell all agreed, 2015 was the Albemarle’s worst since the late 1970s.

Nathan Hall, an assistant professor with the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences, acknowledged there were in fact blooms occurring prior to 2015, and even between the 1980s and the 2000s.

“However, the general consensus is that the bloom situation has gotten worse, and it’s backed up by the state’s chlorophyll a data that has doubled at many stations in the past 20 years,” Hall said.

Paerl said that as far as the “early days” of Chowan River blooms go, excessive nutrient inputs from an upstream fertilizer plant in Tunis and a pulp and paper mill on the Virginia side of the river were largely to blame.

“As far as agriculture goes, one of the main culprits from agricultural runoff is actually nitrogen,” Paerl said.

Paerl said he wouldn’t solely blame agriculture for the nutrients. While he said there is more general agricultural activity in the basin, there is also gradual urbanization.

“If you drive across the bridge there, the Chowan bridge to Edenton, you’ll see there’s more condos along the water there, and you know everyone likes to have green grass all the way down to the edge of the water, and to do that you’ve got to apply more fertilizers,” he said.

“So I would not point the finger at only agriculture, it’s combined human pressure on the system that’s happening,” Paerl said.

“When inputs from these plants were greatly reduced, the blooms dissipated, so this was considered a success story with regard to nutrient management,” Paerl said. “It is less clear why the resurgence in blooms has occurred, but it is likely a combination of gradual increases in nutrient loading and climatic changes.”

This includes more extreme climatic conditions like increased episodic storms, related runoff and protracted droughts.

Ervin speculated that increased rain could be contributing to the blooms and also wondered if disturbances such as dredging on the river could be stirring up nutrients deposited in the riverbed during the days when the fertilizer plant was operating.

“There is an urgent need to get a better understanding of what the combination of environmental drivers is that is leading to the resurgence of blooms,” Paerl said.

Uncharted waters for spreading blooms

Paerl expects a similar solution as in the 70’s – nitrogen and phosphorus inputs need to be reduced. But that reduction may need to be greater than before, as other conditions such as climatic events and weather patterns have become more favorable for blooms.

“The bar has been set higher, so to speak,” Paerl said.

The issue in getting over this bar, however, is funding.

“No one has really done these experiments yet to actually determine what those reductions need to be,” Paerl said.

Paerl and his colleagues have anticipated this resurgence as a result of water warming associated with climate change and the associated increase in extreme precipitation events. Similar resurgences have occurred nationwide, for example, in Lake Erie and the Mississippi River.

He said Lake Erie’s last big blooms had also been resolved in the 1970s. This summer, he is on a team funded to study the causes of the reappearance of blooms there.

Paerl and his colleagues recently proposed studies in grant applications, but they were unable to get the funding.

“It’s frustrating because you know we’re pretty geared up to look at this issue, we’ve written several proposals to pursue it. I’ve warned them for at least two years that this was going to happen again and now it’s happened, so that’s where we’re at,” he said.

For now, researchers at the institute are lending their expertise to the ARC&D Council, while they conduct a grant-funded study begun in 2017. The council is based in Edenton and heavily relies on citizen scientists to monitor and determine the causes of blooms. So far, the study has found blooms are occurring in areas of slow-moving, shallow water.

After no appearance last year, there was a large bloom earlier this summer covering about 1,600 acres in the lower Little River. Powell attributed this to a dry spring, early summer and slow water movement during a hot spell. The bloom didn’t last long, Powell said, but it was pretty extensive.

“They popped up in some new areas that we haven’t seen them before,” Powell said, citing both Little River and the Perquimans River.

A community’s call for help

The ARC&D Council has endorsed a “Water Quality Call to Action,” which individuals, organizations and municipalities are joining to ask state officials to do more for their struggling waterways.

“The algal blooms we are seeing here in the warmer months are sure signs of a sick river,” according to a statement on the Pasquotank County government website. “These algal blooms are a threat to fisheries, recreation, property values, human health, and our regional economy.”

The resolution asks the state legislature to secure funds to strengthen “critical” drainage and water quality infrastructure in the area, specifically seeking increased monitoring. It suggests monitoring would be conducted through local governments, organizations like ARC&D, universities and citizen scientists. It also asks for financial incentives to landowners for maintaining buffer areas of swamp forest and funds for local governments to annually clear debris from creeks, rivers and canals.

Eight counties around the sound, the Pasquotank Soil and Water Conservation District and the Albemarle District of Soil and Water, which covers five counties, have adopted and sent to legislators the resolution.

This story is provided courtesy of North Carolina Health News, a nonprofit news service covering health and environmental issues in North Carolina.