WILMINGTON – Before 2017, few people in southeastern North Carolina were familiar with terms like GenX or the acronym PFAS.

In the two years since the results of a study of the presence of these chemicals in the Cape Fear River was made public, GenX and other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, have become household names.

Supporter Spotlight

The discovery of these chemicals in the Cape Fear River, the drinking water source for tens of thousands in the Cape Fear Region, was just the beginning – a scratch on the surface of an issue that has many questions with too few answers.

A group of 20 researchers from seven North Carolina universities known as the PFAST Network Research Initiative has set out to change that.

Over the next year researchers with the PFAST – the “T” stands for testing – initiative will analyze water samples from each drinking water source in the state, determine the risks of PFAS to private water wells, study which filtration methods best remove PFAS from drinking water, determine how PFAS travels through air emissions and gain a better understanding of how these chemicals impact human health and the environment.

To do this, a series of research teams have been created to tackle the job of finding answers and, in some cases, solutions to the mountain of looming questions about PFAS.

About 200 filled the seats of the Lumina Theater in the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Fisher Student Center Friday afternoon for to hear about the preliminary findings, and objectives and goals of each of the five teams. The PFAST Network, University of North Carolina Wilmington and North Carolina Coastal Federation hosted the forum, Emerging PFAS Contaminants in the Cape Fear Region: University Collaborations on Environmental, Drinking Water and Health Effects.

Supporter Spotlight

North Carolina State University professor Detlef Knappe, a co-investigator of the GenX exposure study that went public in summer 2017, painted a sobering description of the issue.

“We regulate, in the context of drinking water treatment, 100 chemicals,” he said.

PFAS has about 1,000 chemicals.

They are synthetic chemicals that are resistant to heat and are water, grease and stain repellent – making them highly desirable to consumers.

PFAS are in a number of consumer products: carpets, carpet cleaning products, food packaging, furnishings, cosmetics, outdoor gear, clothing, adhesives and sealants, firefighting foam, protective coatings and nonstick cookware.

PFAS are not usually listed on product information, Knappe said, so we’re unaware we’re buying products with these chemicals that are persistent and toxic.

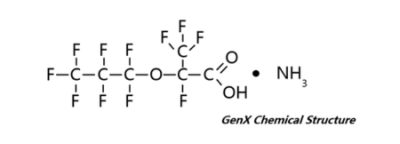

One such PFAS is GenX, the commonly used term for perfluoro-2-propoxypropanoic acid, which is a chemical compound produced to make Teflon. Teflon is used to make nonstick coating surfaces on cookware.

The Chemours Fayetteville Works facility has been releasing GenX and other PFAS into the Cape Fear River since the 1980s.

A GenX exposure study released last November found four PFAS unique to customers of the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority. Blood samples taken from more than 300 New Hanover County residents revealed GenX was not one of them. Researchers involved in that study cautioned the results do not mean GenX is nonexistent in people who drink water sources from the lower Cape Fear River.

Knappe, one of the researchers involved in that study, said Friday that levels of PFAS in the region’s drinking water have begun to quickly drop, something he attributed to the actions of local officials and community outpouring.

“Today, PFAS levels in the Wilmington drinking water are much, much lower than they were two years ago,” Knappe said.

Though at lower levels, these chemicals still exist in drinking water sources.

The job of Team 1 is to sample and analyze PFAS in all public water supplies in the state.

Researchers from Duke University, North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina Charlotte will attempt to answer the question: Is my water safe to drink?

“This is really a difficult question to answer,” Knappe said.

There are regulated contaminants and unregulated contaminants, the latter of which there is no national standard so water utilities cannot say whether water containing these chemicals is safe to drink.

Team 1 will collect about 350 water samples from all 191 municipal surface water intakes and all 149 municipal drinking waters systems treating groundwater in North Carolina to measure PFAS. Later this year, another round of samples will be collected from systems where PFAS have been detected.

Nearly 60 samples have already been collected, including one from a water treatment plant in Maysville, a town of about 1,000 residents in Jones County.

“These small systems fly well often below the radar,” Knappe said. “These systems know much less about the quality of their water than some of the larger systems like Wilmington.”

The sample analysis, conducted at Duke University, found elevated levels of perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOS, and perfluorhexane sulfonate, or PFHxS.

“What we learned is that they are most likely impacted by some firefighting foam that is in their groundwater,” Knappe said. “We’re very sure it’s related somehow related to firefighting activity.”

This revelation has prompted officials in the small town to begin thinking about solutions to improving water quality.

Water sample analyses will be posted on PFAST Network’s website.

In another analysis, this one being conducted by Team 2, private well water will be studied.

Team 2’s goal is to uncover how PFAS is transported through aquifers and predict which private wells are at risk of contamination.

Jacqueline MacDonald Gibson, a professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, said that 1,200 well water samples have been tested around the Chemours facility.

Some of those wells contain levels of contaminants well above the health standard while others do not. Researchers hope to figure out what’s driving this patchwork of contaminated versus noncontaminated wells and determine how long it will take to flush contaminants out of the groundwater.

“Air turns out to be an important pathway for travel of these PFAS contaminants,” MacDonald Gibson said.

The team’s preliminary findings show that a well’s proximity to the Chemours facility and a well’s location relative to wind direction are major factors influencing the levels of GenX in those wells, she said.

Going forward, the team’s goals are to be able to predict which wells are at risk, identify the factors influencing those risks, develop an online tool for well owners to use to predict those risks, and understand the duration in which it will take to flush contaminants like GenX from the water.

Researchers from UNC-Chapel Hill, UNC-Charlotte, N.C. State and Duke that make up Team 3 are delving into identifying the best ways to remove legacy PFAS, or long-lasting substances in the environment, and other substances from drinking water.

Heather Stapleton, an associate professor in environmental chemistry at Duke, explained that the structure of legacy PFAS allows them to go through water filtration systems at public utilities without being removed.

Team 3 researchers are examining 29 types of PFAS, 10 types of high-pressure membrane filtration systems and three types of water, including surface water, groundwater and deionized water.

Preliminary results show that a nanocomposite membrane and saltwater membrane removed 99.8 percent of the chemicals.

One researcher on the team studying the effectiveness of in-home filtration methods has so far found that reverse osmosis is the best at removing PFAS. Refrigerator filters and pitcher filters removed anywhere from 36 percent to as much as 73 percent of the 12 PFAS examined in the study.

“We basically see 100 percent removal for all the PFAS chemicals we’ve looked at,” Stapleton said.

The team hopes to complete its research by January 2020, with recommendations on the types of materials to use in large-scale water treatment plants to optimize the removal of PFASs.

A key question of Team 4 will involve breaking down which contaminants are present in ambient air in the state, in wet deposition – rain, sleet, snow or fog – and dry deposition, which is in the form of gases and dust particles.

This proposed research may provide information about the atmospheric reactions, transport and deposition of PFAS to surface and ground waters tapped as drinking water supplies.

Team 5, according to Jamie DeWitt, an associate professor of pharmacology and toxicology at East Carolina University, has several complex research objectives to better understand the effects of PFAS on human health and the Cape Fear River’s environment.

“This is a very complicated team because we have a lot of different questions we’re trying to ask,” DeWitt said.

What happens to our bodies as we drink, breath and ingest PFAS compounds into our bodies?

The small, independent teams within Team 5 will study a variety of things, including whether PFAS accumulate in wildlife, how the chemicals affect a person’s immune system, how plants take up PFAS and various sources of PFAS entering drinking water, such as landfills and wastewater treatment plants.