This is the second installment in a special reporting series on coastal resiliency. Read Part 1.

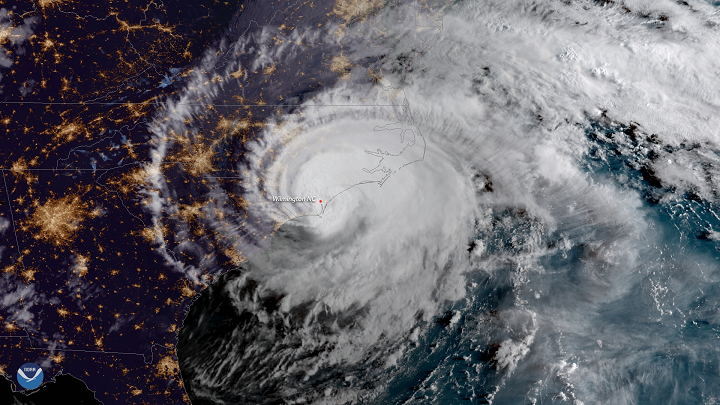

As Category 4 Hurricane Florence plowed toward the North Carolina coast last September, an all-hands weather code red reverberated throughout the eastern part of the state.

Supporter Spotlight

Mandatory evacuations ensued. Universities closed. National news reports warned travelers to steer clear of driving through the state’s I-95 corridor. Administrators and emergency personnel of towns on barrier islands braced for the worst as they moved inland to ride out the storm, one that as of Sept. 10, 2018, packed winds of 140 mph.

Three days later, Florence was downgraded to a Category 1, a storm that, according to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, would bring dangerous winds likely to damage roofs, shingles, vinyl siding and gutters, snap large branches and topple shallow-rooted trees, and cause power outages.

Moving at a snail’s pace, moisture-packed Florence did much more after coming ashore near Wrightsville Beach Sept. 14, 2018.

Moving at a snail’s pace, moisture-packed Florence did much more after coming ashore near Wrightsville Beach Sept. 14, 2018.

Over the course of four days, Hurricane Florence’s record-breaking storm surge – 9 to 13 feet – and rainfall amounts that exceeded 35 inches left a wake of devastation that included dozens of deaths and an estimated $17 billion in destruction in the state.

Say hello to the poster child of what a newly released Zurich North America study calls the “new normal” of hurricanes, storms that researchers say require bucking current storm preparedness methods, taking a holistic approach to addressing risks and changing the terminology we use to communicate possible post-storm consequences.

Supporter Spotlight

Florence and the 2016 Hurricane Matthew, researchers warn, are not anomalies.

Large, slow-moving, catastrophic flood-causing rainfall – these are the ingredients of a new recipe of hurricanes coastal residents, policy makers and governments can expect in our changing climate.

Unveiling Weaknesses

With each hurricane comes a series of lessons.

“Every disaster provides ample learning,” said Michael Szönyi, flood resilience program lead for Zurich and one of the authors of the study, “Hurricane Florence: Building resilience for the new normal.”

Included in the study, a collaborative work of Zurich North America, the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance, and the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-International that was published in April, are highlights of real-life experiences and some of the lessons taken from Hurricane Florence.

After a new generator failed three times during the storm, New Hanover County emergency management personnel were forced to switch to a backup generator and move the emergency operations center to the other side of the building.

The 911 call center was offline for eight hours during the move.

In New Bern, a man confident he had prepared well to ride out the storm in his home was getting to ready to escape rising floodwaters and hunker down on the second floor of his house when firefighters knocked on his door.

The house adjacent to his was in flames, set ablaze by a generator that caught fire, and firefighters could not guarantee his safety.

The man told researchers the experience taught him to heed future evacuation notices.

These are just some of the stories the study’s authors collected during interviews with local and state government officials, Federal Emergency Management Agency officials, business owners, nonprofits, academics and private property owners.

Hurricane Florence further served as a reminder the ongoing risks posed by coal ash ponds and large-scale hog farm waste storage facilities in flood-vulnerable areas, according to the study.

More than 39 million gallons of raw or partially treated human sewage from inundated wastewater treatment systems and other sources spilled into the Cape Fear River from Greensboro to New Hanover County.

“Hog and poultry waste, fertilizers, and pesticides were flushed from thousands of acres of land,” according to the study.

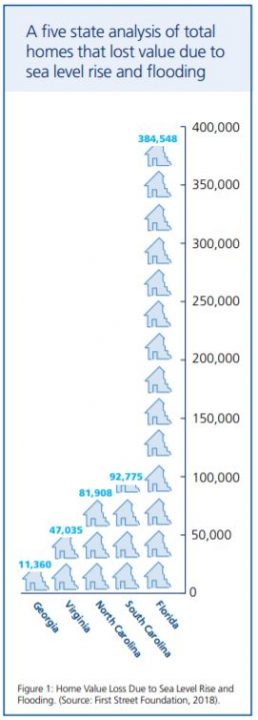

On the socioeconomic side, Florence is a testament to an imbalance in storm recovery between the haves and have-nots.

Home and business owners with the assets and insurance are generally recovering better than those without, the study found.

Smaller communities with higher poverty rates in North Carolina’s coastal plain were still recovering from Hurricane Matthew when Florence struck the coast.

“This pattern of shortened recovery time and limited recovery support from various authorities exacerbates existing disparities in recovery,” the study states. “Higher income, better resourced and insured communities recover and rebuild faster, and more likely in time for the next storm, than their lower-income, resource scarce neighbors.”

That evidence, those stories – they help researchers identify the lessons learned from Hurricane Florence, use them to come up with recommendations to enhance flood resilience plans and share those recommendations to flood-risk prone communities around the world.

The idea, Szönyi said, is to shift the needle for communities to move from being less reactive to putting more preventive measures in place so they are best prepared for future storms.

Getting Ready for the Worst

ISET-International research associate and fellow author Rachel Norton said North Carolina put into practice some of the lessons learned after Hurricane Matthew.

“The state and local governments had learned from that event and they did collaborate and put in best practices from what they saw,” Norton said. “I think it’s a process to build those relationships ahead of time. It’s something that we see as important and needs to be worked on.”

Working together to address systemic risks is one of the recommendations made in the Zurich study and will likely be discussed at next month’s North Carolina Coastal Resilience Summit in Havelock.

.@battleshipnc is facing its next challenge head-on. Check out our report on #HurricaneFlorence to learn about the measures in innovation and #resilience to preserve the #WWII battleship. #HurricaneSeason @ISETInt https://t.co/ilqssMZe9U pic.twitter.com/Biuq2sQgeT

— Zurich (@ZurichNA) May 2, 2019

“We came up with these recommendations through talking with people,” Norton said. “It’s not that we magically came up with these. There is a way forward. It can seem challenging.”

Norton is in the lineup of speakers at the June 11-12 summit.

Participants of the event, hosted by the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management and North Carolina Coastal Federation, will learn about and discuss the development of the state’s Climate Risk Assessment and Resilience Plan. The plan is being designed to boost the coastal region’s preparedness for everything from sea level rise and coastal and riverine flooding to increasing extreme weather and changing groundwater conditions.

Christian Kamrath, a coastal resilience specialist with the division, said that getting people to think clearly about long-term preparations is difficult when they’re in midst of a slow recovery.

“Some places are in a constant state of recovery,” he said. “There’s a lot of stress on everyone, particularly staff at the local level.”

But Kamrath said there is a shift in thinking and more is being done in pre-disaster mitigation planning.

It’s going to take working outside of the normal silos of work state and local governments have done in the past and addressing difficult topics, including critically assessing building in high-risk areas and discouraging development in those areas.

“Acknowledging this, communities should plan for the impacts of eroding shorelines, disincentivize development in areas of risk, and plan in advance so that if state or federal buy-outs are offered in the future they have already begun the discussions necessary to inform decisions,” according to the study.

Retreating is one of the least popular options discussed in coastal communities, particularly those dealing chronic erosion at inlets.

“There’s a lot that goes into thinking about where we build,” Norton said. “I think that one, yes, it’s a recommendation, but it is going to take a lot of thinking about how we take that recommendation and put in on the ground.”

Szönyi said that, big picture, looking at further coastal expansion raises questions about financing constant beach repair and recovery, if there is a limit to that and, if so, what that limit is.

Another way in which communities can help private property owners and business owners prepare is by helping them understand which insurance is best for them.

And, there is a better way in which to communicate storm threats, according to the study.

In other words, hurricanes can no longer be judged alone by the Saffir-Simpson scale, which was introduced in 1973.

“Trying to explain a natural event with one parameter or one number is generally challenging,” Szönyi said. “We’ve seen this not just in hurricanes. It also happens, for example, with earthquakes. I think we need to look at how to communicate all the components of the hazards. It’s changing and it’s going to be more frequent and it’s going to be more severe.”

Kamrath agrees that more effectively communicating the risks is a challenge.

Weighing storm risks primarily on the Saffir-Simpson scale has “been ingrained in our culture for decades,” he said.

North Carolina now has the online Flood Inundation Mapping Alert Network, or FIMAN, that monitors weather radar and stream, sound and river gauges. FIMAN predicts floods and breaks down different scenarios of flood severity and projected community impacts.

“Seeing is really telling a story,” Kamrath said. “There’s some great visualization tools coming out. I have hope in the promise of certain technology being able to communicate that risk.”