This is another in a series of reports on coastal resilience.

ALLIGATOR — It was a full house at the Alligator Community Building, where folks came out on a late October evening because they were sick to death of floodwaters sitting for months in their yards.

Supporter Spotlight

Alligator, a speck of a community in the Tyrrell County swamplands, is no stranger to flooding. But their land doesn’t drain like before, residents told public officials. Ditches are clogged, and water seems to be coming more than it’s going.

“What happens to the landowner who is flooded out and doesn’t have a pump?” a lifelong Alligator resident asked officials with the state forestry service, state coastal management, the U.S. Corps of Engineers and the county who were in attendance.

Suggestions and promises were made, and some people from the agencies came back later and drove around to look at problem areas.

More than six months later, with the storm season looming, nothing appears to have changed, except that the land has finally dried out, said Michael Combs, one of the meeting organizers.

“We really would like to know what can be done,” Combs said in a recent interview. “I can’t say it will be (ditch) cleaning alone. There really needs to be extensive work done, elevating the roads and probably elevating the homes.”

Supporter Spotlight

But Combs, 55, who serves as associate minister at Alligator Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, worries that Alligator is too small – 70 or so people, he guessed – and too poor to even get attention, no less the help it needs.

“There’s not many resources at all,” Combs said. “We strive to get things done, but we can only do so much.”

Resilience in Tyrrell County is a built-in character trait of people in this rural county, but that term in the context of climate change is not common talk here. Sea level rise was part of a presentation at the beginning of the community meeting, but that was the only mention. The concern, simply, was flooding.

“When I was a child, I rode bicycles all over this land,” one older man said. Then there was his neighbor, he recalled, who had “kept his yard like a golf green. And now you can’t walk on it.”

As one of the state’s poorest counties, and its least populated, Tyrrell is already disadvantaged. But according to a 2016 report in the journal Nature Climate Change, Tyrrell has earned another unfortunate ranking: It is the No. 1 county among 319 U.S. coastal counties facing long-term risks from sea level rise.

By 2100, the report said, 94 percent of the Tyrrell’s projected population is expected to be vulnerable to inundation. The study, led by Mathew Hauer at the University of Georgia, was unique for looking at a combination of projected sea level rise and projected population.

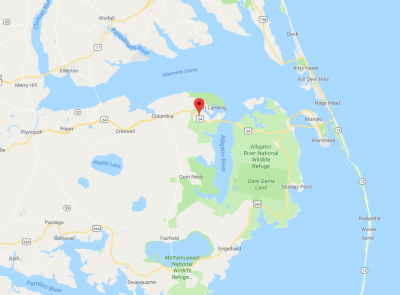

And the Alligator Peninsula, which encompasses the communities of Alligator, Fort Landing, Goat Neck and Pledger Landing, is the most vulnerable area in the county.

Tucked in the northeast corner of Tyrrell between U.S. 64 and the Albemarle Sound and intersected by the Little Alligator River, the peninsula, at only about 1 foot above sea level, depends on an old and barely maintained network of ditches and canals for drainage. Gravity is useless; any water movement is wind-driven.

“We are dealing with sustainability issues at all levels here and climate is just one part of it,” David Clegg, the county manager, said in an interview after the study was released. “Places like Tyrrell County need to exist and we need to build economic development that celebrates what we are.”

Tyrrell’s 600 square miles is about 50 percent public land, including Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and Pettigrew State Park, making its tax revenue paltry at best, Clegg said. Many of the county’s 3,600 residents – only 1,900 of whom pay taxes – work in farming, timber and fishing, all industries with decreasing opportunity. The average annual salary in the county is about $30,000, the state’s lowest. Young people routinely leave and rarely return, diminishing its population.

But public land means more to the county than decreased tax revenue, the manager added. It also means the county has no control over that land – or its drainage. In the Alligator area alone, the state owns the 10,000-acre Palmetto-Peartree Preserve, the 14,178-acre Alligator River Game Lands, the 1,441-acre Texas Plantation Game Land water impoundments and the 2,100-acre J. Morgan Futch Game Land. Elsewhere in the county off Highway 94, there are state-owned Buck Ridge, privately-owned Cherry Farms and the federally-owned Pocosin Lakes.

“You’ve got competing interests, literally looking at each other,” Clegg said. On one side of the road, water may be drained, which ends up flooding the other side, or one entity is trying to lower the water table, he said, while the entity across the road is rewetting the land.

“Then you’ve got 12,000 bears galloping all over it. Then you’ve got the wolves. Then you’ve got the foxes and the alligators,” Clegg said. Hunters, conservationists, government officials, farmers, private property owners, he said, all “earnestly” believe they’re doing the right thing.

“I’m in the middle of it, saying I want economic development,” Clegg said.

Still furious over the state wind moratorium that killed a wind project that would have provided hundreds of thousands of dollars in tax revenue to the county, Clegg said he is proud of the “innovative” agricultural technologies used by the county’s farms that produce potatoes, corn, canola, lavender, timber and soybeans at high per-acre production levels. But until the tax base increases, he said the county cannot afford to provide the services they want to provide.

Clegg, who was Tyrrell’s first-ever county manager, had served 20 years in the Commerce Department under former governors, Hunt, Easley and Perdue. Tyrrell is so small, it is a statistical anomaly in the state – “significantly insignificant,” as Clegg put it. It is even too small, he said, to fit the state’s small school model.

“If something other than aquaculture or agriculture is going to move the needle, it’s going to have to be ecotourism,” he said.

Clegg adamantly objects to offhanded suggestions that people “should just leave.” Not only does he support people’s desire to stay in Tyrrell County, he insists that the county deserves help from the government to raise their houses or improve their drainage systems and infrastructure. But he acknowledges that there are many pressures and competing forces that may defeat even the best of intentions.

“It all comes down to economics – is it economically feasible to do it?” he asked. “At some point, I think you reach a point where you’ve gone as far as you can go.”

And finding solutions will take persistence, Nathan “Tommy” Everett, chair of the Tyrrell County Board of Commissioners, told community members at the October meeting.

“What we’ve got to do is find out what the problem is, “ he said. “We’ve got to document it. I can tell you, it ain’t going to happen overnight.”

This past winter, some people were walking through sewage in their yards, Everett said in a recent interview. And he confirmed that the ditch systems are overgrown with weeds and filled with sediment and debris.

“My guess is they haven’t been maintained since Jim Hunt went out of office,” he said, referring to Gov. Hunt, who left in 2001. And since then, more farmland has been developed, he said, meaning more water is being pumped off the land rather than draining on the land.

Plus, flooding has been exacerbated in recent years by more intense rainfall.

The county, with the help of various grants, has already replaced well water with a municipal water system, and is in the process of hooking up Alligator and other communities to its new municipal sewer system, Everett said, adding that the county’s goal is to eventually extend the system to all areas.

Everett, 67, who has lived his entire life in the county, agreed that people are noticing a change in flooding. But he said it’s hard to pinpoint the reason.

“I think almost everyone realizes that for some reason tides are higher and that flooding is more prevalent during storms,” he said, adding, “Only the strong survive here.”

Some people do blame climate change, he said, but many believe that “it has a great deal to do with Oregon Inlet” because the Albemarle Sound goes out through the inlet. And it seems that work on U.S. 64 by the state Department of Transportation may have altered the hydraulics in Piney Marsh west of the Scuppernong River bridge, he said. Before, floodwater would go through the marsh. Now it to go around it, and the highway acts like a dike. As a result, flooding has gotten worse in Columbia, the county seat.

Everett said that the folks in Alligator see a stormwater management district as their salvation, but he said that the community does not have the finances to maintain such a costly dike and pump system. And being bordered by the Albemarle Sound and Alligator Creek might make it impractical.

“You pump one place and it comes in from somewhere else,” he said.

Ty Fleming, the county soil and water conservation district manager, said that he has lived in Tyrrell “forever” and he has observed that there’s more water and it’s standing for longer periods, especially in Alligator.

“There’s some really old folks down there – in their 80s – and they say ‘It used to not be like this’,” he said. “And I just don’t have an answer for them.”

Alligator’s drainage is worsened by a layer of clay about 15 inches below the sandy surface, Fleming said. In 2007, he said the county installed floodgates in some canals and replaced 30 drainage pipes under driveways. But maintenance of the county’s ditches – some of which may be centuries old – is complicated by jurisdictional issues. The DOT, for instance, claim that some of the roadside ditches are not within its right of way, he said. Ditches may be on private property, or on property managed by a nonprofit, or an unknown entity, or inaccessible.

“Really, the only thing the county is able to do is we’re spraying the ditches to kill the invasive aquatic weeds,” Fleming said.

Combs said the more frequent and long-lasting flooding has put even more stress on Alligator. “There’s been times we can’t even get to the cemetery to a have a funeral,” he said. “During the winter months, my yard never dried out.”

Economic stress, he said, has hollowed out what is one of the state’s oldest historically black communities. Today, Alligator is a mix of black, white and Hispanic residents, many of whom fish or farm for a living. With young people leaving for better jobs and education, Combs said, the elders left behind no longer have the tight family connections.

Combs said he’s still optimistic that things will improve for his community, and that Tyrrell will have development that helps the economy. If not, he fears that Alligator won’t be able to survive, and “everyone just goes their different ways.”

But East Carolina University coastal geologist Stan Riggs, however, sees a flip side to the gloomy prospects. Tyrrell County, in fact, is blessed with some of the most “spectacular” blackwater bodies and wild lands in the country, said Riggs, who has recently released two studies on ecotourism in the Albemarle Peninsula and the Scuppernong region.

Riggs has studied the Outer Banks and northeastern North Carolina since the 1970s, and to him, resilience for Tyrrell communities means making water work for them, and looking at their resources as golden opportunities.

“You have to learn to live with the dynamics of the system,” he said in an interview. “If the dynamics are changing, then we have to change with them.”

Sometimes people will have to relocate, he said, but if people plan ahead, they may open up more options. Young people need to learn to be comfortable on the water like the older generations, and to appreciate the value of the richness that’s surrounding them.

Take blackwater, the somewhat sinister-sounding name for its coffee or tea color. The water takes on its various dark shades from draining through the vast swamp forests, marshes and pocosin lands. Although it’s dark, it’s sediment-free and clear.

Indeed, the region, with its abundant wildlife, expansive lands and vast estuarine waters, has been referred to by some as the “Yellowstone of the East,” Riggs said.

“All these economic councils, everybody’s looking for an IBM or a Weyerhaeuser,” Riggs said. “The whole point here is they have natural resources that can represent an economy. They have this incredible resource.”