COROLLA – Any day now, legal action may be taken to challenge construction of the proposed Mid-Currituck Bridge, but it would be par for the course for a project that has been presumed dead for much of four decades.

Plans for the 4.7-mile, two-lane span between Currituck County’s mainland and Outer Banks reached a milestone last month that not long ago seemed impossible: approval to move forward.

Supporter Spotlight

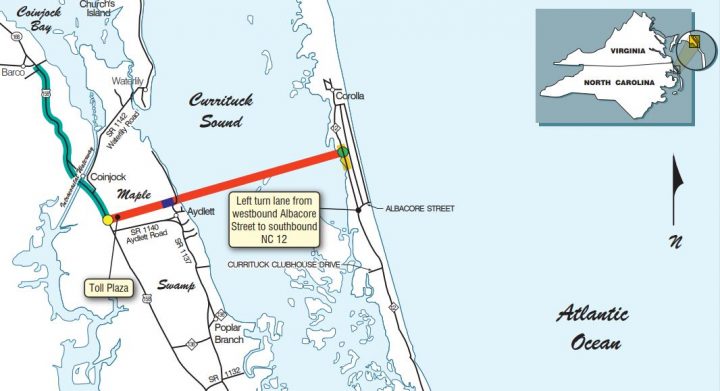

With the Federal Highway Administration’s Record of Decision on March 8, the North Carolina Department of Transportation and the North Carolina Turnpike Authority have the official go-ahead to seek environmental permits, acquire rights of way and advance plans for construction of the $490 million bridge, Project No. R-2576. The project also includes a 1.5-mile bridge over Maple Swamp in Aydlett, the project’s mainland entrance about 25 miles south of the Virginia state line.

But debate about the project’s environmental effects, its cost and its very necessity continues unabated.

“This is a massive boondoggle,” said John Grattan, a member of Concerned Citizens and Visitors Opposed to the Mid-Currituck Bridge, or NOMCB, and the North Carolina Wildlife Federation. “A half a billion dollars (would be spent) for a bridge that is going to fulfill its function relieving traffic on only 13 weekends a year.”

“This is a massive boondoggle.”

John Grattan, NOMCB

Bridge proponents, including officials in Dare and Currituck counties and the towns of Duck, Southern Shores and Kitty Hawk, say it is needed to relieve hourslong summer congestion on U.S. 158 approaching the Wright Memorial Bridge and on N.C. 12 between Southern Shores and Corolla. Not only is the traffic an inconvenience to visitors and residents alike, they say, it is a safety hazard in a resort area subject to intense weather. In addition to shaving an hour off the time for visitors coming to the Outer Banks from Virginia, the bridge would also increase employment and cut commuting time for seasonal staff, proponents contend.

“The Mid-Currituck Bridge will provide much-needed transportation improvements for hurricane evacuation clearance times and connectivity to the Outer Banks,” Chris Werner, acting executive director of the North Carolina Turnpike Authority, said in a statement in March.

Supporter Spotlight

Estimating Demand

According to Currituck Economic Development, the county’s year-round population is projected to grow from the current 25,000 to 42,000 by 2045, and the seasonal population is expected to increase by more than 30,000 in the same period. Without the second bridge, NCDOT estimated that the hurricane evacuations by 2035 would take 36 hours. State rules call for clearance time – the hours from the start of evacuation until the last vehicle is gone – to be 18 hours.

But the Southern Environmental Law Center, which is representing NOMCB and the Wildlife Federation, contends that NCDOT and the Turnpike Authority are required under federal regulations to update the environmental impact statement, or EIS, that was completed in 2012 because it is based on outdated information, including about traffic volume and sea level rise and storm surge data. The groups have requested that a supplemental EIS be completed to update the information in the 2012 document that was the basis for the just-issued Record of Decision.

“Since that time, there have been substantial changes made to the project and to the proposed alternative solutions,” SELC attorney Kym Hunter said in a March 18 letter to the agencies requesting a supplemental EIS. “In addition, significant new information has developed with regard to project costs, environmental impacts, traffic forecasts, hurricane evacuation modeling, development assumptions, and financing plans.”

In an interview, Hunter also said that recent estimates show that there would be fewer vehicles using the bridge than earlier projections, which would affect not only congestion and hurricane evacuation forecasts, but also potential toll revenue.

She noted that the state had set aside $178 million in the NCDOT Division 1 budget for the project, leaving about $300 million to be provided by tolls or some other revenue source. Tolls could be as much as $28 each way during peak season, Hunter said, and NCDOT costs could consume “a considerable part” of the Division 1 budget.

The need for the bridge as an evacuation route, Hunter said, is undercut by the latest climate science showing increased sea level rise and storm surge.

“So, during a hurricane, it’s very likely that this won’t even be a usable bridge,” Hunter said.

Meanwhile, Hunter said SELC is waiting for a response to its request for a supplemental environmental impact statement.

“We have asked NCDOT to prepare a SEIS, which is legally required because of the many changes that have occurred since 2012, and because the current documentation is outdated and inadequate,” Hunter said in an email dated April 1. “If the Department will not do so we will be forced to take legal action on behalf of our clients.”

The law center has 150 days from the record of decision, or until Aug. 5, to file a legal challenge.

Another alternative developed by an engineer hired by the groups proposes a combined approach that would cost about $146 million and would include the following:

- Building a flyover at the intersection of U.S. 159 and N.C 12.

- Replacing traffic lights with roundabouts.

- Using staggered check-in and check-out times and electronic keys for weekly rental customers.

- Creating manned traffic controls at peak times.

- Developing a traffic app for visitors to help avoid congestion.

Long, Troubled History

An east-west crossing over Currituck Sound was first identified as a need in 1975. Since then, the Mid-Currituck Bridge has lurched along in a one-step-forward, two-steps-back planning process. After formal planning finally began for the bridge in 1995, nearly every state and federal stakeholder agency raised objections. Among the objections were concerns that development would be encouraged in an area unsuited to handle it.

The proposal was eventually tabled. But in 2006, the project was revived, and it was delegated to the Turnpike Authority to develop a public-private partnership to fund and build the bridge as a toll project with a price tag of about $600 million. At the time, tolls were estimated to cost about $8 each way during summer and $6 during the remainder of the year.

By 2012, the proposed cost was reduced to about $410 million, but the North Carolina General Assembly declined to provide funding. Two years later, the project was added to NCDOT’s 10-year transportation improvement plan, but it didn’t meet the state’s priorities for funding, which use scores projects receive based on population and traffic. So again, the project was put on hold.

After an amendment to the transportation plan that considered more local input, the project was moved up in the priority list, qualified for construction and was included as a funded project in the 2016-25 state transportation improvement plan.

According to the federal decision, the bridge is to be financed by a combination of toll revenue bonds; a Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act, or TIFIA, loan; Grant Anticipation Revenue Vehicle, or GARVEE bonds; and state matching funds. The total cost including utilities, environmental mitigation and rights of way is $490.59 million.

Rodger Rochelle, NCDOT project engineer, said that the department determined that changes since the 2012 environmental statement were not substantive enough to warrant a supplemental environmental statement.

The public-private partnership concept was dropped after the agencies were unable to come to an agreement with the developer on costs to build and maintain the bridge for 50 years, Rochelle added.

“The alignment and the scope of the project essentially has not changed since the EIS,” he said in an interview.

Lacking Infrastructure

Rochelle said that a toll estimate is expected to be available after a revenue and traffic study is completed. He declined to estimate when it would be done.

But Jen Symonds, NOMCB’s steering committee chair, said that the bridge proposal does not consider that the village of Corolla and Carova, the unpaved community to its north, lack the infrastructure to handle the increased traffic that the bridge would bring. Carova can barely handle the crowds that come for wild horse tours, she said.

“They’re tearing up the beaches,” Symonds said. “You’ve got vacationers up there using the beach as a toilet.”

But Currituck County Manager Dan Scanlon said that the county has made and is continuing to make significant improvements to the beach areas, including a greenway, a pedestrian plan and additional parking, sidewalks and restrooms. The county also has recently updated its land use plan, he said. But there’s a difference of opinion, he said, about the bridge’s potential effect.

“There’s a finite amount of development left,” Scanlon said. “I think we are addressing growth potential.”

But to Symonds, the whole idea of the bridge improving hurricane evacuation or easing congestion makes no sense, considering that the bridge will only bring more traffic.

“The bridge has one lane each way, so it will queue back up,” she said. “And it’s not going to help that traffic that they experience on N.C. 12. They’re going to be going south and north to get to the rental offices.”

Traffic is a fact of life in all vacation areas, Symonds said, whether it’s a ski resort or a beach resort.

“You could build a thousand of these bridges,” she said. “It’s not going to help the road capacity on N.C. 12. Deal with it.”