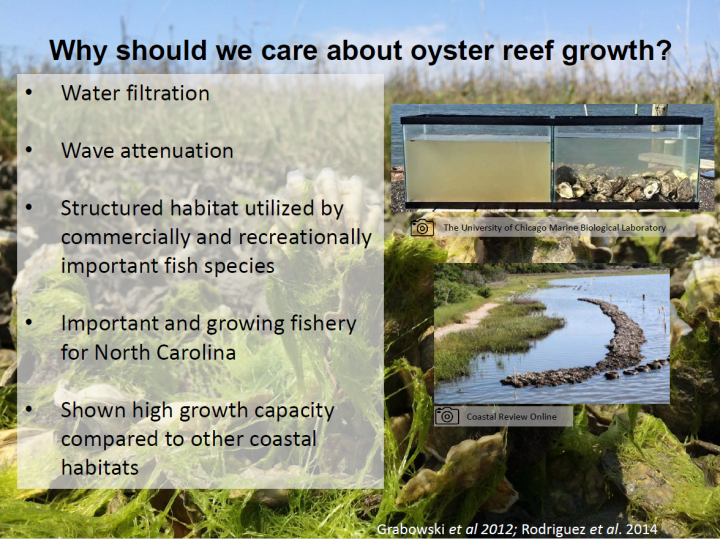

MOREHEAD CITY – Why should we care about oyster reef growth?

Molly Bost asked the three dozen or so gathered for the first Research Applied to Managing the Coast Symposium, or RAMCS, March 29 at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences.

Supporter Spotlight

“First off, oysters are important because they filter water,” Bost continued, adding that oyster reefs attenuate waves, provide habitat for commercially and recreationally important fish and are an important, growing fishery for the state.

Bost was among the 15 UNC IMS faculty and students presenting in one of three areas of research: coastal resilience, water quality and fisheries during the daylong symposium.

A UNC IMS doctoral student, her adviser is professor Tony Rodriguez, who organized RAMCS with the help of his lab, Bost and Master of Science students Carson Miller and Jessamin Straub.

Rodriguez told Coastal Review Online following the symposium that, in addition to the presentations on oyster reefs, some takeaways included learning that “oil spills in the Gulf of Mexico really didn’t impact finfish very much, which was surprising and an important lesson for North Carolina, especially considering the recent attention to offshore oil exploration in our state.”

Also, nutrient loading and algal blooms in the Neuse River estuary are often in the news, but the problem is more widespread, and Albemarle Sound has similar issues, he said.

Supporter Spotlight

Along with Rodriguez, working with Bost on her research were Miller and Duke University Marine Lab Postdoctoral Associate Justin Ridge, who conducted previous work with Rodriguez on oyster reef growth. Bost used the unpublished data. The research was funded by North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality Coastal Recreational Fishing License.

Along with Rodriguez, working with Bost on her research were Miller and Duke University Marine Lab Postdoctoral Associate Justin Ridge, who conducted previous work with Rodriguez on oyster reef growth. Bost used the unpublished data. The research was funded by North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality Coastal Recreational Fishing License.

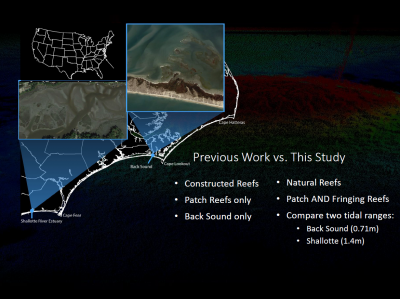

To put her results into context, Bost explained to the crowd at the symposium the previous work measuring the growth of constructed oyster patch reefs in Back Sound, specifically around Middle Marsh, in Carteret County. A patch reef is not connected to any other intertidal habitat except mud or sand, unlike a fringing reef, which forms along the perimeter of a salt marsh.

The project “looked at where in the tidal frame is best to construct an oyster reef,” Bost said.

Bost explained that LIDAR, or light detection and ranging, scans of the oyster reefs Ridge made in 2010 and again in 2012 were used to find the optimal growth zone, or where oysters grow best.

The findings from the previous work led to Bost looking further into how the optimal growth zones for constructed reefs compared to those of natural reefs and whether the zones varied with the tidal ranges. She said they continued to work in Back Sound to find these answers and included a site in the Shallotte River estuary in Brunswick County.

To reiterate, she said, the previous work was on constructed patch reefs in Back Sound. Bost with her research added looking at natural reefs, both patch and fringing reefs, and comparing the two tidal ranges, with Back Sound being the lower tidal range and Shallotte the higher tidal range. The team used the same methods as the previous work.

They found that the optimal growth zone on natural reefs in general occurred at a higher elevation and across a smaller range of elevations than constructed reefs, and at the higher tidal ranges, there’s a larger span of elevations for the optimal growth zone.

They found that the optimal growth zone on natural reefs in general occurred at a higher elevation and across a smaller range of elevations than constructed reefs, and at the higher tidal ranges, there’s a larger span of elevations for the optimal growth zone.

“Basically what I’m taking from this, and what I would like you all to take from this, is that there’s no one project design that maximizes restored oyster reef growth rates everywhere, there’s a lot of things to take into consideration,” she said.

Bost said that she’d like to determine how old the reefs are to see if age makes a difference.

In an interview, Bost explained that her presentation included research the Rodriguez lab had conducted that piggy-backed off research from Ridge’s PhD work.

“This research is still in progress and just like any good project, the data we’ve collected is raising even more questions than we started with,” she said, adding that the symposium was the perfect opportunity to talk about the work in a relaxed environment.

Rodriguez told Coastal Review Online that he organized the symposium because, “We commonly need to communicate research results to managers, conservationists, and end users.

“In grant proposals we need to outline how that information exchange will happen,” he said. “In a (North Carolina) Sea Grant project I’m working on, I proposed to host a meeting and decided to open it up to all of the faculty at IMS. RAMCS is a one-stop shop for communicating research results. It’s much more efficient than all of us doing that individually.”

The entire UNC IMS faculty was invited to present research results with management applications, he said. “No one was left out. Those who responded were included in the symposium.”

Research was presented from the institute’s Fodrie, Piehler, Hall, Luettich, Paerl, Lindquist and Rodriguez labs.

Organizers said the symposium will likely become an annual event, but with a few tweaks to encourage participants to stay for the whole session.

Bost told Coastal Review Online that she helped Rodriguez organize the symposium. Their lab brainstormed on how to make it successful in connecting stakeholders and funding sources to the research in an informal way, “while putting faces to the many names on both sides.”