A scathing new report from the Rachel Carson Council examines the wood pellet biofuel industry, specifically the industry leader’s operations in North Carolina, and its “severely adverse” environmental and health effects.

Wood pellet producer Enviva called the report misleading and factually incorrect.

Supporter Spotlight

The report, “Clear Cut: Wood Pellet Production, the Destruction of Forests, and the Case for Environmental Justice,” highlights what it calls “the fallacies and economic and political injustices surrounding the industry,” specifically Enviva and its North Carolina operations. The council released the report Jan. 7, a week before Enviva secured a state air quality permit to produce more pellets than originally planned at its plant under construction in Hamlet in Richmond County.

Founded in 1965, the Rachel Carson Council is a national environmental organization envisioned by Rachel Carson to carry on her work that focuses on environmental justice, climate change, toxic waste and chemicals and industrial farming, according to the group’s website. “Clear Cut” is the Rachel Carson Council’s fourth report.

“North Carolina is unique because it houses more Enviva facilities than any other part of the country,” according to the report, which notes that the soon-to-be four wood pellet plants in the state are among the largest in the world with an annual production capacity of about 2 million tons, or more than 15 percent of the total U.S. annual production capacity. “This level of production, though, has put a severe strain on the environment and communities in North Carolina.”

“North Carolina is unique because it houses more Enviva facilities than any other part of the country,” according to the report, which notes that the soon-to-be four wood pellet plants in the state are among the largest in the world with an annual production capacity of about 2 million tons, or more than 15 percent of the total U.S. annual production capacity. “This level of production, though, has put a severe strain on the environment and communities in North Carolina.”

The “Clear Cut” report says that the industry is driving massive clear-cutting of U.S. forests in the Southeast and harms the health of surrounding communities. The report describes “the unjust economics” and political forces allowing the industry to continue its adverse effects.

“‘Clear Cut’ demonstrates that the industry is unnecessary and harmful, particularly to poor communities of color,” according to the council.

Supporter Spotlight

Enviva Vice President and Chief Sustainability Officer Jennifer Jenkins, in response to Coastal Review Online’s request for comment, called the report “an agenda-driven piece designed and written to discredit the environmental and economic benefits of the forest products industry.

“The piece is full of misleading and argumentative claims that are supported not by peer-reviewed literature, but by informal reports from the organizations themselves that perpetuate these false claims.”

Rachel Carson Council President and CEO Bob Musil said the report authors “paid very serious attention” to the science related to wood pellet production and its use as biofuel as well as the “human story” associated with the industry.

“It wasn’t agenda driven because the Rachel Carson Council, like Rachel Carson, follows the science,” Musil said. “We’re working with people who over the years have been paying very close attention to the wood pellet industry because they live there, they work there in these communities. What’s important is, in any big solution to any energy question, we all need to make sure that the people who live and work in and around these facilities have a say in what’s going on in terms of environmental justice. We offer instructions on how to get involved.”

Enviva produces pellets at three North Carolina facilities: one in Ahoskie, which began operations in November 2011; another in Northampton County, near Gaston, Roanoke Rapids and Garysburg; and a third in Sampson County, near Faison and Clinton. The fourth pellet facility planned for Hamlet is set to commence operations early this year.

Jenkins, while not addressing the specifics in the report, characterized the biomass industry as an integrated part of the forest products industry. “The forest products industry, inclusive of timber income, is responsible for $29.4 billion of economic activity in the state of North Carolina, is one of the state’s largest exports and accounts for 145,000 jobs,” Jenkins said in the company’s response.

Enviva exports the pellets via its terminal at the North Carolina Port of Wilmington, as well as ports in Alabama, Florida and Virginia. Most pellets are destined for the United Kingdom, which under renewable energy directives from the early 2000s had large carbon-reduction goals but few options for renewable energy in replacing its coal infrastructure. Wood pellets can be burned to generate electricity with coal in coal power plants or without coal in converted coal power plants to achieve the U.K.’s carbon-reduction commitments, the report notes.

“Though touted as a clean, environmentally safe alternative to fossil fuels, wood pellets are a carbon-intense, destructive and polluting industry based in flawed carbon accounting in international agreements,” according to the report. “Wood pellet material sourcing leads to massive deforestation of critical habitats, and Enviva alone is responsible for 50 acres a day of clear-cut land. Pellet production facilities release dangerous air pollutants including particulate matter and volatile organic compounds putting surrounding communities at higher risk for health complications.”

Environmental Justice Communities

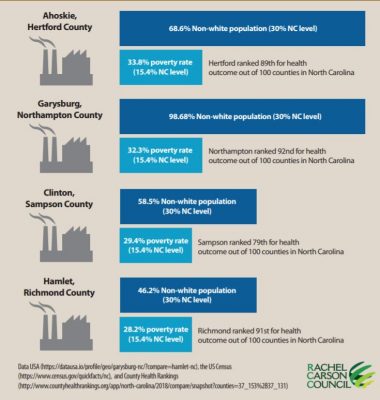

Enviva operates seven processing plants in the southeastern United States that produce 3.5 million metric tons of wood pellets yearly. Half of the company’s plants are in North Carolina and all of those are in environmental justice communities, including the one under construction.

“These communities directly suffer three-fold from wood pellet production,” according to the report. “First, as wood pellet plants source within a 70 mile radius, the communities experience higher rates of tree loss leading to lower air and water quality and increased risk of flooding. Second, wood pellet production plants in North Carolina until recently have skirted Clean Air Act requirements, freely emitting dangerous pollutants into the communities. Third, and finally, these communities sit on the coastal plain of North Carolina and are under direct threat from climate change which wood pellet production and consumption contribute to.”

Enviva mills the wood, dries it and forms the pellets in a press. “During the extrusion process, the lignin in the wood plasticizes forming a natural ‘glue’ that holds the pellet together after production,” according to the company.

Wood pellets, according to the report, release carbon dioxide and pollutants when first chipped in mills. When oven dried and compressed to form the product, volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, particulate matter, nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide are released.

The company’s Hamlet plant was initially permitted to produce up to 537,625 oven-dried tons, or ODT, per year of wood pellets using up to 75 percent softwood. The new permit authorizes increased production to 625,011 ODT per year with the installation of new milling and pollution-control equipment.

The report notes that nearly half of Hamlet’s 6,000 residents are black, Hispanic and Native American, and about three in 10 residents live below the federal poverty level. The Hamlet plant is next to a neighborhood where four out of five residents are black and more than a third live below the federal poverty line.

Jenkins said the report falsely portrays the process and status of air permitting and Enviva’s compliance efforts. She said Enviva is currently awaiting issuance of air permits for the installation and operation of state-of-the art equipment to significantly reduce airborne emissions.

“After the installation of these controls, almost all of our facilities will be minor sources of emissions. We are also seeking to expand our production and utilize more softwood to meet our growing customer requirements in conjunction with reducing and controlling air emissions from our facilities,” Jenkins said.

She said that in the few instances where Enviva’s facilities will remain major sources of emissions, the company has applied for or obtained permits that require the installation of equipment to reduce air emissions in accordance with all federal and state laws and regulations.

“Enviva chooses its particular site locations because we see a great opportunity to grow our business, to create employment in economically disadvantaged areas and to assist in the positive growth of local communities,” Jenkins said, adding that the report fails to mention the company’s community engagement efforts and the positive impact in the communities.

Enviva’s North Carolina operations directly employ about 350 workers. For every job created at an Enviva facility, more than two additional domestic jobs are created in the community, Jenkins said.

Enviva supports about 2,500 private landowners who choose to maintain their property as sustainable, working forests rather than converting it to commercial, agricultural or residential development, Jenkins said.

Enviva’s North Carolina operations generate more than half a billion dollars in investment and support more than 1,100 direct and indirect jobs, Jenkins said, adding that the company expects that number to grow by 25 percent in 2019. Enviva’s 2017 payroll totaled more than $20 million and the company contributed nearly $3.5 million in tax revenue and generated nearly $500 million in economic activity in North Carolina.

The report claims the economic growth comes at the expense of surrounding communities. Opponents have called for a state study of the environmental justice implications for the Hamlet facility.

Deforestation Claims

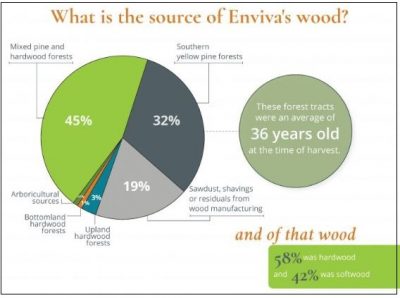

The company harvests wood from what it describes as low-grade wood fiber, or wood that’s unsuitable for other uses because it’s too small or has defects, disease or infestation, as well as tops, limbs or parts of trees that can’t be made into lumber. It also uses weaker or deformed trees felled to promote the growth of higher value timber, known as “thinnings,” and mill residues such as chips, sawdust and other wood industry byproducts.

But each of these sources is at some point reliant on the practice of clear-cutting forests or cutting down all of the trees in a given area of land, according to the report. “Nevertheless, many still consider the industry as ‘green’ since it claims that it predominantly uses sources that would otherwise be thrown away.”

The report says that by 2015, it had become clear that residual wood waste would not be enough to supply the wood pellet market. “So, Enviva had to turn to whole wood sources. The corporation primarily consumes pine trees found in softwood forests as well as a mixture of bottomland and upland hardwood trees. The softwood tree supply is often sourced primarily from pine plantations that are abundant in North Carolina, but the bottomland and upland hardwood trees generally come from older growth, biodiverse regions critical to the environmental health of North Carolina. Unfortunately, nearly half of all bottomland hardwoods lie within the sourcing perimeters of Enviva’s three operational plants in North Carolina,” according to the report.

The report states that, given increasing demand in European and Asian markets, Enviva will increasingly need to clear-cut forests, threatening the state’s human population and biodiversity, exacerbating flooding and putting at risk ground water and surface water quality.

“Forests are critical in mitigating the threats of climate change, and it is more urgent than ever to invest in nature to protect our country against the damage that Hurricane Florence and storms like it pile onto our most vulnerable communities in years to come,” according to the report.

Jenkins responded that Enviva accepts only the lowest-quality wood from a harvest and only wood from working forests, while the rest of the wood goes to other forest products markets. She called the report’s harvest statistics unsupported and misleading. Enviva does not agree to purchase wood coming from land that will not stay as forest, she said.

“Every year in the Southeastern United States overall, and indeed in Enviva’s supply areas, forest inventory and carbon stocks increase year over year. In other words, for every ton that is removed from the forest through harvest, more than one ton grows back,” Jenkins said, adding that forest inventory has doubled since 1953. That can be attributed to robust markets for forest products, which encourage landowners to invest in their forests, Jenkins said.

“Floodplain forests are precious, and we agree they should be protected,” Jenkins said. “We have robust systems in place to ensure that we do not take from sensitive forests, and we have made substantial investments in forest conservation via our Enviva Forest Conservation Fund. We should note that landowners have choices, however, and so our decision to walk away rarely keeps the forest standing.”

Global Effects

Privately owned Enviva was founded in 2004 to develop a cleaner energy alternative to fossil fuels, according to the company’s website. “In particular, we wanted to offer electric utilities a fuel to replace coal, enabling them to generate power without interruption while reducing their greenhouse gas emissions.”

The Rachel Carson Council’s report states that burning wood pellets releases 65 percent more carbon dioxide than coal per megawatt hour. “Industrial-scale production of wood pellets is entirely unnecessary to combat climate change,” according to the report, and it steers subsidies and resources away from renewable sources such as wind and solar.

The U.K.’s Drax Power Station, which receives much of Enviva’ s pellet production, burns 13 million tons of wood pellets to generate electricity each year, emitting up to 23 million tons of carbon dioxide, according to the report. “Such a huge amount could only be sequestered if 60 million tree seedlings were planted and allowed to grow for a full decade. Instead, each year these emissions are compounded by additional burning, pushing carbon neutrality further out of reach for the industry.”

Jenkins, in her response, referred to her blog on Enviva’s website, where she states that bioenergy provides significant and immediate greenhouse gas savings, compared to coal. “This effect is most appropriately calculated at the landscape scale, which is the scale at which forests are managed: every year 2 percent of the forest in the SE US is harvested while the remaining 98 percent of the forest continues to grow and store carbon. In fact, every year there is more wood stored in the forest than there was the year before, and so any emissions from harvest are more than compensated – immediately – by sequestration. When bioenergy is used to replace coal, we’re reducing GHG emissions even further by allowing that coal to stay underground.”

According to the report, the Drax Power Station’s transition from coal to wood will ultimately increase CO2 emissions, but because of what the report calls “accounting errors” in the EU Energy Directive, Drax avoids tens of millions of dollars in fees for pollution, while receiving hundreds of millions in subsidies.

Europe accounts for more than 75 percent of global wood pellet demand, of which a third goes to power plants to be burned for electricity generation. Japan and South Korea are among the countries increasingly incorporating wood pellets into their renewable energy mix.