OCEAN ISLE BEACH – The deadline has been extended to Jan. 7 to comment on a proposed consent order, the comprehensive resolution to the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, contamination from Chemours’ Fayetteville Works facility.

Supporter Spotlight

The proposed consent order announced in late November among the Department of Environmental Quality, Cape Fear River Watch and Chemours requires the company to “dramatically reduce GenX air emissions, provide permanent replacement drinking water supplies and pay a civil penalty to DEQ,” according to the release.

DEQ announced the deadline extension Dec. 21, when the public comment period was initially set to close, as well as posted a fact sheet to address concerns regarding the proposed consent order.

Comments on the proposed consent order may be submitted by email to comments.chemours@ncdenr.

Sheila Holman, state Department of Environmental Quality assistant secretary, was invited to review with the Coastal Resources Commission during its November meeting the GenX investigation timeline since June 2017, when the news first broke of the contamination in the Cape Fear River and details on the consent order.

“Given the importance of the GenX issue to coastal communities, the commission invited Sheila Holman, DEQ’s Assistant Secretary for the Environment, to provide background information and an update on the department’s ongoing work on this issue,” Renee Cahoon, CRC chair, told Coastal Review Online.

The 13-member CRC establishes policies for the state Coastal Management Program and adopts rules for both the Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, and the North Carolina Dredge and Fill Act. The CRC is also responsible for adopting policies on coastal issues. “As such, it’s important to share updates on DEQ’s work and obtain the commission’s insight and expertise, as we partner to protect North Carolina’s coastal resource,” Holman said in an interview.

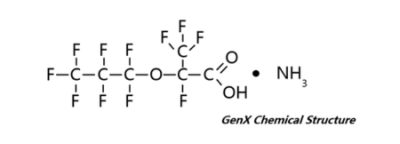

Supporter Spotlight

During the CRC meeting, Holman told the members, “We began this journey looking into this particular contaminant and then broadening to the more comprehensive PFAS family in June of 2017,” when DEQ learned of the ongoing research by Detlef Knappe, North Carolina State University professor, and other researchers including Mark Strynar, in the EPA’s Office of Research and Development, on the different perfluorinated compounds that Chemours began using after phasing out “what we call the legacy compounds,” the C8 compounds, perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, she said.

The scientists discovered GenX along with several other perfluorinated compounds in the Cape Fear River.

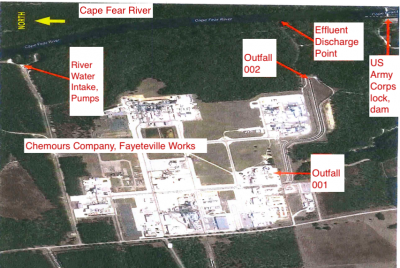

After the news broke June 7, 2017, Holman said that Chemours on June 21, 2017, agreed to stop discharges from their process wastewater, which contained GenX.

“About that time I was feeling pretty good, that ‘Hey! We’ve discovered the problem and we’ve gotten to a quick resolution’,” she said. “Turns out that the problem is a bit broader than that.”

First of all, she continued, as the wastewater discharge at the facility outfall was monitored, the values of GenX dropped, but not to zero, and would often spike.

“We were continuing to understand where GenX was coming from,” she said. “Not only was the department, but also the company trying to understand the different sources of GenX into the waste streams.”

That August, DEQ also began testing the groundwater wells on the property, the results for which take from two to five weeks for the turnaround on the analysis, she said. Of the 14 wells sampled, 13 had GenX at concentrations ranging from about 500 parts per trillion, or ppt, up to about 60,000 ppt.

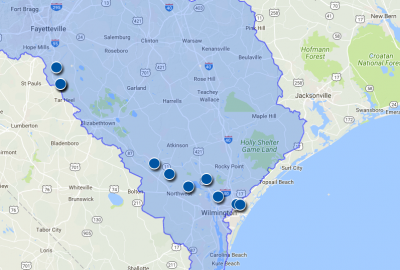

“That obviously led to concerns as to whether groundwater containing GenX had moved off-site and possibly impacted private wells at properties near the facility,” she said.

DEQ and Chemours began testing private wells. More than 800 wells have been tested so far, with around 200 having GenX above the provisional health goal established by the state Department of Health and Human Services in July 2017. The health goal for exposure to GenX in drinking water is 140 nanograms per liter, or ppt.

As data from some of the private, off-site wells were studied, they realized that the contamination could not have come from a normal groundwater flow, which pointed to air emissions from the facility, she said.

The Division of Air Quality began requiring the company perform smokestack testing for GenX and other perfluorinated compounds as well as started conducting rainwater analysis. “We were finding GenX in rainwater up to 7, 8 miles from the plant in several hundred parts per trillion.”

DEQ began working with Chemours about what could be done to reduce air emissions and a lot has happened in that time frame, she added.

With surface water, Holman explained, in addition to the company volunteering to stopping the process wastewater streams that they thought contained GenX from entering into the Cape Fear, DEQ starting Nov. 30, 2017, began requiring all process wastewater no longer enter into the Cape Fear River and has since been captured and disposed off-site. There has been a decline in concentrations of surface water values in the river for GenX and other perfluorinated compounds.

“The good news is for those drinking water systems downstream, even since July 2017, we saw much lower values, certainly below the provisional health goal set by (Department of Health and Human Services),” she said.

On the air quality front, the company has taken several steps already, including installing carbon adsorption units that has resulted in around a 40 percent reduction in the air emissions of the GenX compounds. The rainwater data indicates much less GenX and perfluorinated compounds in the rainwater since being connected in May, she added.

In October, a new scrubber was installed at one of the process units most responsible for GenX emissions, leading to an overall 72 percent reduction in the air emissions and more is planned.

As for groundwater, different rain events show spikes of GenX at the outfall, even after all the process wastewater was stopped being released into the Cape Fear. DEQ required the company to look at the cause of those spikes, Holman said.

“Much of it was believed to be from stormwater and existing PFAS and GenX compounds on the ground picked up by the stormwater and carried into the outfall.”

She said that the company is working to address the on-site soil contamination that could be causing the intermittent spikes.

“There’s ongoing plans to address the groundwater and soil remediation on-site and we’ll also be requiring an off-site plan to address the off-site contamination,” she said.

Holman explained to the CRC that “The purpose of talking through that is to understand the depth and time that it’s taken to get through that investigation. All of that work, I think, has led to the consent decree that we announced (in November).”

The proposed consent order is an agreement among DEQ, Cape Fear River Watch and Chemours, and “hits on all the key elements of the investigation.” Public comment is welcome until Jan. 7 on the proposed consent order. The original deadline of Dec. 21 was extended by DEQ.

By the end of this year, there will be new emission controls that would achieve a 92 percent reduction of GenX compounds air emissions facility wide, Holman explained, and by next year, will have installed a thermal oxidizer to obtain an overall 99.99 percent efficiency in the removal of all PFAS compounds from the facility.

“There are solutions to get the perfluorinated compounds out of air emissions,” she said.

In addition, there’s a requirement to provide permanent drinking water either in the form of public water supplies or whole house filtration systems for those with drinking water wells with GenX above 140 ppt. There is a provision for reverse osmosis systems for homes and others with combined PFAS levels above 70 ppt or any individual PFAS compound above 10 ppt.

“I think that (the proposed consent order) highlights that we are moved to get to good resolution as quickly as possible,” Holman said.

Holman said that the EPA is working with other states to collectively address the PFAS family of compounds.

“We’re continuing to try and figure out how to address the PFAS family more broadly.”