From a North Carolina Health News report

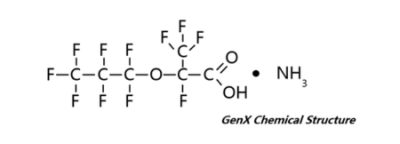

North Carolina’s health goal for GenX in drinking water would drop by one-fifth if state regulators choose to use preliminary data on the compound’s toxicity from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Supporter Spotlight

That newly published data, a reference dose representing a maximum level of daily oral exposure considered unlikely to affect a person’s health over a lifetime, resulted from an EPA assessment of GenX’s toxicity, a draft of which the agency released on Nov. 14.

The assessment also identified specific potential health hazards posed by GenX. Among other things, the liver may be especially susceptible and available data are “suggestive of cancer.”

EPA’s proposed reference dose for GenX is 0.00008 milligrams per kilogram of body weight for daily lifetime exposure. That equates to 80 parts per trillion (ppt), a conversion that simplifies comparisons to the concentration of GenX that North Carolina considers safe in drinking water.

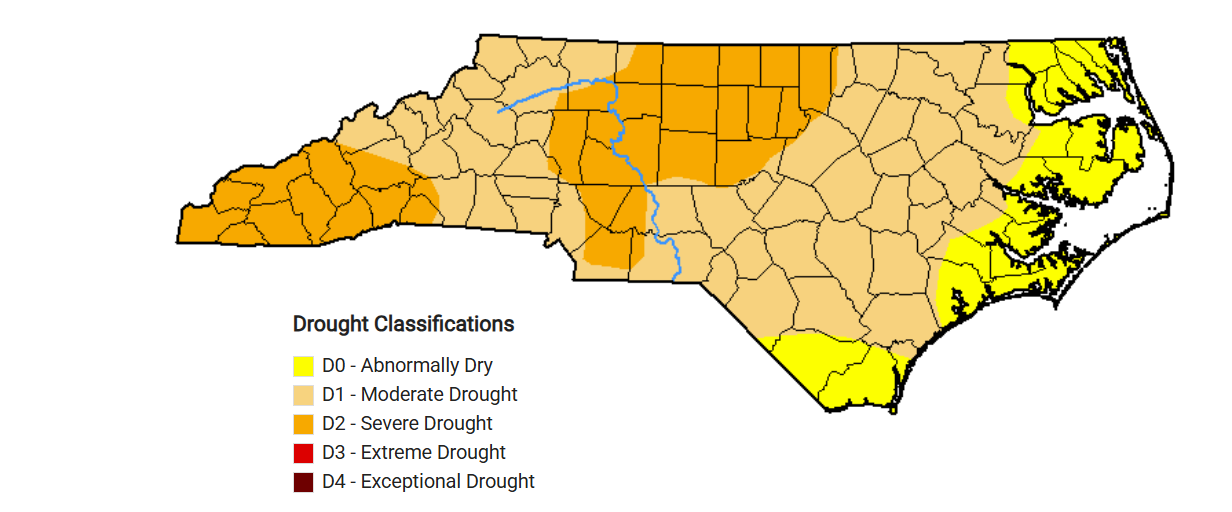

GenX contamination surfaced as a public health issue in June 2017, following media reports that researchers had found GenX and similar substances in the Cape Fear River, downstream from the Chemours chemical plant on the Bladen-Cumberland county line near Fayetteville.

In November 2017, under pressure from the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality, Chemours stopped discharging its manufacturing-related wastewater.

Supporter Spotlight

Last year, the state Department of Health and Human Services, or DHHS, derived its own reference dose of 100 ppt as one of a number of factors used to calculate North Carolina’s interim health goal of 140 ppt in drinking water.

In addition to the reference dose, DHHS also based its calculations on potential risks to a particularly vulnerable human population, infants, and assumed that drinking water would account for one-fifth of total exposure to GenX.

Plugging EPA’s draft reference dose into DHHS’ formula would reduce the health goal to 112 ppt.

Jamie DeWitt, a professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology at East Carolina University, said, “EPA’s proposal appears to align more closely with the state’s conclusions, though its methodology differed from the state in a number of ways.”

For now, the state will stick with the current health goal, DHHS spokesman Cobey Culton said in an email response.

“The EPA report on GenX toxicity is in draft form and is subject to change after the public comment period. In the interim, we will continue to use our provisional health goal for drinking water of 140 parts per trillion that has been evaluated by the Secretaries’ Science Advisory Board. When the EPA releases its final reference dose, we will revisit our provisional health goal for GenX.”

The EPA will finalize the toxicity assessment following a 60-day window for public comments. The comment period is not yet open.

“While we are in the process of reviewing the draft EPA toxicity assessment for GenX, it is clear from the EPA report that GenX is significantly less hazardous than its predecessor compounds,” said Chemours spokeswoman Lisa Randall.

The EPA’s risk assessment includes a summary of potential health hazards posed by exposure to GenX, based on available animal studies. In particular, the EPA assessment highlighted the liver as vulnerable.

“Overall, the available oral toxicity studies show that the liver is sensitive to GenX chemicals,” according to an EPA fact sheet on the draft assessment. “Animal studies have shown health effects in the kidney, blood, immune system, developing fetus and especially in the liver following oral exposure. The data are suggestive of cancer.”

The 80 ppt reference dose in the draft report is for chronic or lifetime exposure. In addition, the report included a reference dose for subchronic exposure — more than a year but less than a lifetime — of 0.0002 milligrams per kilogram of body weight, or 200 ppt.

The EPA also released a draft risk assessment for perfluorobutane sulfonic acid, or PFBS, another fluorochemical.

Unlike GenX, PFBS “doesn’t appear at high levels in N.C. drinking water intakes,” said Detlef Knappe, an N.C. State professor and one of the researchers who discovered GenX in the Cape Fear River and downstream utilities.

This story is provided courtesy of North Carolina Health News, a website covering health and environmental news in North Carolina. Coastal Review Online is partnering with North Carolina Health News to provide readers with more environmental and lifestyle stories of interest about our coast.