Reprinted from North Carolina Health News

MOREHEAD CITY — When Brett Froelich saw Hurricane Florence taking aim at the North Carolina coast, he saw an opportunity.

Supporter Spotlight

So, even as Florence’s winds were screaming past the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences where he is an associate professor, Froelich was planning on how to get test kits out to physicians and other health care providers who would be providing care after the storm.

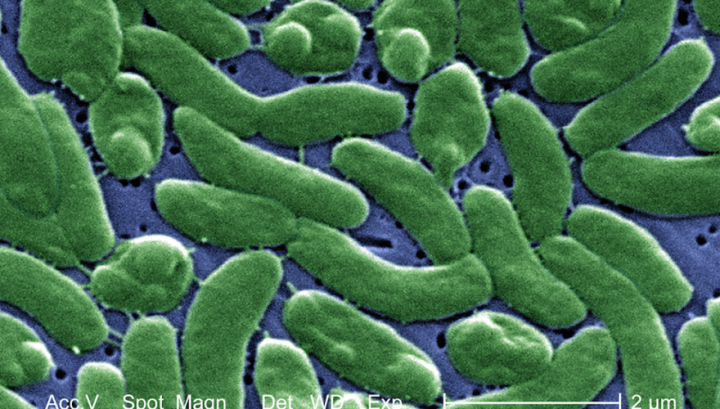

Froelich studies the kinds of bacteria that are present in water stirred up by hurricane winds and surges. The target of his current research is a species of the nasty pathogen known as vibrio, which is in the family of bacteria that includes cholera.

“We’re not too worried about cholera. We have excellent sanitation and things like that,” he said reassuringly. “What we are worried about are a couple of other species, Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus.”

Those two species of vibrio live in shellfish and also in the waters that host other shellfish. People who eat raw shellfish inoculated with either of these bacteria can get pretty sick.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates between 52,000 and 80,000 cases of food poisoning each year are attributable to vibrio.

Supporter Spotlight

But another problem is when people come in contact with either of the vibrio species through an open wound.

“Say they cut themselves on a rock, or they poke their finger while baiting a hook or something like that and some of the salt water gets in there,” he said. “The bacteria can then get into that wound and cause a life-threatening infection.”

During Hurricane Katrina, there were 22 confirmed cases of Vibrio vulnificus-based wound infections, said Froelich’s colleague, Rachel Noble, a professor at IMS.

“There were five deaths that happened from those,” she said.

Dangerous floodwaters

Vibrio infections happen more often in summer months when the water is warm and the bacteria are able to multiply. The good news is that the bacteria are very susceptible to treatment if a person with a red and oozing wound receives treatment early.

“If a patient were to come in, and they say, ‘Look, I got cut and it looks infected,’ and the doctor gave them antibiotics they’d probably be fine,” he said. “But if they got infected, and then think, ‘Well, let me sleep on it and see how it looks tomorrow,’ the next day it might be too late.”

V. vulnificus left untreated has a 50 percent fatality rate.

“That’s even with aggressive medical treatment, which usually involves intravenous antibiotics, amputation of infected limbs and things like that,” Froelich said.

That’s what happened to a Wilmington man, who died after cutting his leg during hurricane cleanup and getting floodwater into the wound. He died on September 25 after having his infected leg amputated.

NC Health News could not confirm that V. vulnificus was the cause of his infection, but New Hanover County deputy health director David Howard said the pathogen is a big concern for his department. His agency put out a press release on the 25th warning local residents about the risk of vibrio.

Howard said if people “have to come in contact with floodwater, say cleaning up the house, wear boots or waders, gloves.”

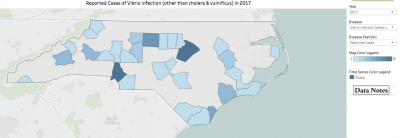

In 2017, 64 people in North Carolina were reported to have acquired vibrio infections, five of them were V. vulnificus, but Froelich believes that number might be higher, and that’s why he saw an opportunity in Florence.

Marine bacterial infections inland

When a patient shows up at a doctor’s office with an angry, infected wound, most of the time, the doctor won’t culture the bacteria that are in the wound but will simply give antibiotics. The good news is that vibrio is very responsive to antibiotics and will easily get killed off.

But Froelich wants to get the doctors near the coast and inland to culture those wounds in the wake of Florence to get a better idea of the prevalence of these infections.

“The storm surge pushed water up the estuary and up the river, bringing with it that salty water,” Froelich said. “When the water is less salty that (vibrio) can proliferate, but they also require some salt. So they can’t survive in fresh water.

“If you go way up into the river, normally all the way up to New Bern, you wouldn’t find these things at all. But with the storm surge, it pushed the salt water that far up and extends the risk way upriver.”

Even as Florence was dumping rain on the coast, he scrambled to assemble kits containing sterile swabs, culture media, instructions, gloves and a consent form. Then he drove around, distributing the kits to providers as far inland as New Bern.

Froelich worried that people are at risk further inland who might think they’re safe from encountering coastal pathogens. He said that the large storm surges extend the places that vibrio can be found and places not normally considered a risk area now are.

“People who are just walking through standing water [there] might have a wound or get a wound and then these bacteria can infect them without them ever having gone into the coastal waters,” he said. “Basically, people who are technically on land can get a marine bacterial infection.”

He said the vibrio can enter a wound as small as an ant or mosquito bite.

“Little cuts you didn’t know you had, ones you can’t even see, that’s all it takes,” he said.

Long lasting

What makes vibrio even more of a horror movie pathogen is its persistence. Froelich explained that if soil containing vibrio dries up, it enters what’s called a “viable but non-culturable state.”

“It essentially just really, really, really slows down its metabolism to almost nothing and then once conditions improve, that is to say, enough water, enough salt and then the temperature is right, they come back out,” he said. “Because they grow so fast, they can double every 20 minutes and can react like that to changing conditions.”

He said in his lab they had an old test tube sitting in the back on the shelf, forgotten for close to 20 years.

“When we got to it, the tube was nothing but dried-up salt crystals. We took that, added water to it, shook it up, got them to grow,” he said.

There is one upside: fully salty ocean water isn’t as welcoming to vibrio, so, as coastal waters flush out the fresh water coming downstream, the risk on beaches diminishes. As of this weekend, most precautions on the ocean side of the state’s barrier islands have been lifted. But people who wade in brackish, part-salty water will have to continue to be on guard.

This story is provided courtesy of North Carolina Health News, a website covering health and environmental news in North Carolina. Coastal Review Online is partnering with North Carolina Health News to provide readers with more environmental and lifestyle stories of interest about our coast.