At some point in the recovery phase of nearly every major storm in North Carolina, there’s a shift from a flood response to a housing crisis.

In the short term, there is emergency funding for temporary housing as flooded-out homes and businesses are gutted and, if possible, made livable again. The Federal Emergency Management Agency provides funds for hotels and short-term rentals, but despite talk of resilience, in the long run there is little in place to break the cycle of residents returning to areas that are proven vulnerable to flooding time and again.

Supporter Spotlight

Grady McCallie, policy director at the North Carolina Conservation Network, said that as environmental organizations craft their proposals for policy changes and what to fund, there’s a recognition that there needs to be a comprehensive vision for dealing with increased flooding and more severe storms in the state’s coastal plain.

“The idea is, ‘how do we get stuff out of the floodplain that shouldn’t be in floodplain?’ And then, ‘how do we manage the floodplain in the future?’” McCallie said. Housing, he said, is a key part of that.

“Just getting people back into their homes is not a long-term solution. If all we do is get everybody back to the same place they were before Florence struck that wouldn’t be enough, because some other one is going to come along.”

Moving people out of the floodplain is going to take a long-term effort, he said, starting with making sure they have somewhere to go that’s affordable. “You can’t just buy people out with nowhere to go.”

In the coming months, as policy makers look at a recovery effort that will in all likelihood overlap with those started two years ago after Hurricane Matthew, moving more people out of the floodplain will be an overarching goal. It’s much of what resilience boils down to in eastern North Carolina.

Supporter Spotlight

Moving homes and businesses has proven to be a difficult, expensive process, however, and as recent evidence of little progress on long-term housing in response to Hurricane Matthew shows, it’s also a painfully slow process.

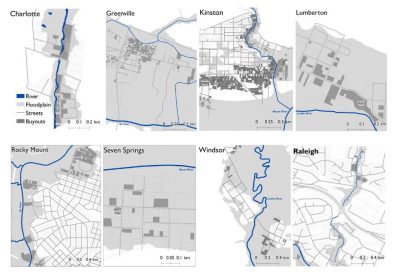

University of North Carolina Chapel Hill researchers Todd BenDor and David Salvesen, who recently published a report on buyouts that looked at strategies and tracked what happened to properties in eight North Carolina communities, said the impact of Hurricane Florence as the state is still recovering from Hurricane Matthew is evidence of the need for a long-term strategy for buyouts and housing for eastern North Carolina.

The report, funded by a grant from the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory and released in August, found a number of flaws in the way buyouts are done, first that they’re almost always reactive and not a part of an overall strategy.

“I don’t want to give the impression I’m against buyouts, I think they are an important part of mitigation, but the way they’re currently designed isn’t working for municipalities or for homeowners,” said Salvesen, a research associate with the Institute for the Environment who specializes in land use and assistance to communities. “Often these are done in haste after a disaster when there is little time and few options and that doesn’t work. Municipalities get stuck with this checkerboard pattern of buyouts because they can’t get everybody to participate.”

People don’t want to move for a variety of reasons, he said, such as longtime family ties to properties, wanting to stay near friends and most often, not being able to afford a move.

“Unless those issues are addressed you’re not going to get all the homeowners to participate,” Salvesen said. “What that means is a local government saddled with this scattershot of vacant lots they have to take care of.”

For many towns, maintaining what the study terms a “checkerboard” of holdouts and bought-out lots has added to maintenance budgets as well as preventing the area being converted to public use or returned to its natural state.

“You have to find out a way to string them together, so you can do something to them,” he said. “You can’t create a baseball field if there’s a house sitting on second base.”

BenDor, a professor with University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill’s Department of City and Regional Planning, said the checkerboard result is the opposite of what’s needed.

“It’s the worst of all worlds,” he said. “You still have to maintain the areas when they become public property and you can’t get rid of most of the infrastructure. Part of the fiscal benefits and the environmental benefit is when you remove houses, in theory, you remove the infrastructure.”

The checkerboard problem, he said, means governments still must maintain water and sewer lines and fix roads for just a few residences. “That’s untenable for a lot of lower-income communities,” he said.

In addition, to maintain the properties most communities mow the lots, he said. That’s also the wrong strategy for the environment.

“A city has political pressure to just go in and mow it, which is exactly what we don’t want to be doing in floodplains from an environmental perspective.”

By restoring an area to its natural state, usually a forest, BenDor said, a city can increase its capacity to deal with floodwaters, a move that increases surrounding land values.

Salvesen and BenDor said the sequence for buyouts has to change. Although there are some funds for pre-disaster mitigation, the biggest funding for buyouts comes after a disaster through hazard mitigation and community block grant funding.

That’s the wrong time to do a buyout, Salvesen said.

“Don’t do it after the flood happens, that’s too late,” he said. Everyone is stressed out. It’s a tragic event. You have to do it in advance, but that’s really hard to do because the big chunk of federal money comes after the flood happens. That has to change.”

To make buyouts work, BenDor said, state and local governments need to see them not as a reaction to a disaster but part of a long-term resiliency effort that includes having affordable housing options out of the areas prone to flooding.

“Understanding where people go matters a lot,” he said. “For instance, there’s a lot of evidence that folks that take buyouts actually move into other high-hazard areas. The point of buyouts is to get people out of these flooding situations but if they move directly back into a bad situation that’s a huge problem.”

After Hurricane Fran, a state buyout program augmented incentives for people to relocated outside of the floodplain, he said. It also added encouraged people to stay in their communities.

“Buyouts are not intended to get people to leave the community, they’re to get them out of high hazard situations,” BenDor said.

Defining those areas is another big hurdle for planners.

“Reviewing the floodplain maps every five years is not going to cut it anymore,” BenDor said. “It’s got to be something we have a much better handle on and it’s really worth having a conversation how we can do that.”

In the months ahead, there’ll be a major effort to move people out of harm’s way, he said, “except harm’s way is changing.”

Salvesen said having two major storms close to each other may be changing some attitudes and perhaps the willingness of people to consider buyouts. “There should be enough evidence now from these two major floods that certain parts of the state are more vulnerable than others. We can identify those areas and begin to target buyouts strategically to the places where you get the biggest bang for the buck.”

It’s a situation like what happened after the sequence of Hurricane Fran and Hurricane Floyd, in 1996 and 1999, respectively.

“There were some buyouts after Fran, but not everyone was convinced. They said, ‘Well that’s a once-in-a-lifetime storm, that’s never going to happen again,’” Salvesen said. “And then Floyd happened a few years later, and all of the sudden people were lining up to get buyouts.”

Reading accounts of the recent storm, especially stories of people who also took a hit in Matthew, Salvesen said something similar could happen.

“One of the things that helps convince people to participate in a buyout is a subsequent flood, but we shouldn’t have to wait for that,” he said.