SHACKLEFORD BANKS – The little rover left tire tracks in the sand as it rumbled across the beach on the moonless summer night. Anna Windle followed behind, keeping an eye on the rover while shifting her backpack full of field gear.

It wasn’t a typical evening on Shackleford Banks, where wild horses are more likely to roam the beach than robots. As Windle scanned the shoreline though, she wasn’t looking for horses.

Supporter Spotlight

“Anna came to the lab with interest in doing sea turtle work,” said David Johnston, associate professor of the practice of marine conservation and ecology at Duke University. “It seemed like the perfect opportunity to think about how you would use a terrestrial drone to be able to study an environmental issue, such as sea turtle nesting.”

Windle, a master’s student at the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort, was at Shackleford leading a study on sea turtle nesting and artificial light. Her results indicate that nest density is higher on darker beaches – useful information for North Carolina towns trying to promote sea turtle conservation.

“I wanted to figure out how to quantify the light pollution on our beaches and see how the different levels of light are impacting nesting activity,” Windle explained. “I did determine that there were significantly different nesting densities in different areas of the beaches from different light levels.”

Windle is a member of Johnston’s Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing, or MaRRS, lab, which is at the forefront of using automated technology to explore ecological questions. She is the first to collect high-resolution light measurements from a sea turtle’s perspective.

“Anna’s work highlights the threat of nighttime artificial light that reaches beaches during sea turtle nesting and hatching seasons,” said Matthew Godfrey, sea turtle biologist for the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

Supporter Spotlight

“Anna really correlated a lot of actual nesting data to areas with lower light,” said Trace Cooper, mayor of Atlantic Beach. Cooper explained that he had considered light in terms of “what happens when the turtles hatch, and not really when they’re nesting, and (thinks) that we need to shift some of our policies to reflect that.”

Sea turtles that nest on North Carolina beaches include loggerheads, green turtles, leatherbacks and, rarely, Kemp’s ridley. These species are threatened or endangered, increasing the conservation imperative.

“Sea turtles face many threats, such as habitat loss and entanglement with marine debris,” said Windle. Compared with other challenges though, light pollution is tractable. “It’s a threat, but it’s a manageable threat, because you can turn lights off.”

There are alternatives to turning lights off altogether. Shields can be placed on fixtures to direct light down, rather than out, and low-lying pathway lighting can be used to illuminate beach entrances.

Residents and tourists can play an active role by pulling down window shades. They can turn off oceanfront lights during nesting season, shield them, or add a timer or motion detector.

“All sandy oceanic beaches in North Carolina are used by sea turtles to reproduce,” Godfrey explained. “People visiting our beach can help sea turtles by keeping out of roped-off areas where sea turtle eggs are incubating, and by ensuring that all visible lights in their homes or condos are blocked from reaching the beach from May through November 15, which corresponds to the sea turtle nesting and hatchings season.”

By adopting simple measures, towns and residents can help attract nesting females and increase hatchling survival.

Guiding the Hatchlings

Before Windle’s study, it had been well established that artificial light was a concern for sea turtle hatchlings. Hatchlings use the reflection of the moon and stars on the ocean to orient themselves towards the water. This behavior can prove problematic on well-lit shorelines, where hatchlings might mistake a floodlight for the moon.

“Sea turtles, they don’t have a chance. A small light affects them,” said Michele Lamping, volunteer coordinator of the Atlantic Beach Sea Turtle Nest Monitoring and Protection Project, which is part of the North Carolina Sea Turtle Project. She described a local house with ample outdoor lighting and no window shades. “It’s bright enough I could probably read a book out there.”

The Atlantic Beach Sea Turtle Project aims to increase hatchling survival despite light pollution. Lamping schedules about 60 volunteers to walk segments of the beach every morning during nesting season. If the volunteers spot a nest, they log it on a global sea turtle monitoring website and build a fence around the nest to protect it. Volunteers check on the nests daily, staying on guard as late as 2 a.m. when they suspect a nest might hatch soon.

When the nests begin to boil – a term referring to the appearance of the sand when turtles hatch in unison – the volunteers ensure that the hatchlings reach the ocean. They extend the fencing to the water and stand outside it to redirect errant turtles.

Lamping explained that without the volunteers’ efforts, most of the hatchlings on Atlantic Beach would crawl toward land and die. “So, we’re pretty adamant about trying to find the nests and make sure we don’t miss anything,” she said.

Robots and Turtles

Windle was already interested in sea turtles when she joined the MaRRS lab.

“When Anna started talking about light as an issue for Atlantic sea turtles, as we were talking through that, it became obvious that that would be a really cool mission for our little rover,” recalled Johnston.

The rover is an unmanned autonomous vehicle, a type of drone. “We actually deconstructed an aerial drone, took the autopilot – which is like the autonomous part of the drone – put it on this rover, (and) hooked it up,” Windle said. “And then essentially you just use the same software that you would with a flying drone and just put in waypoints where you want the rover to travel.”

Roughly the size of a nesting female sea turtle, the rover trundles across the beach on large wheels. If it looks like an escapee from Toys R Us, there’s good reason. Doctoral student Everette Newton created the rover from a remote-control car, originally complete with flame decals. Newton and other MaRRS lab members engineered the rover to be compatible with 3D-printed attachments for a range of research needs.

Windle attached two light sensors to the rover, one facing the dunes and one facing forward. She selected moonless summer nights to conduct fieldwork at Atlantic Beach, Fort Macon and Shackleford Banks. The three sites were chosen to represent bright-to-dark conditions, respectively.

On site, the rover scooted along its programmed path, collecting light readings about every 200 feet for 6 to 8 miles. The team followed behind to ensure that the rover didn’t detour into the surf.

“We’re able to measure light very accurately and very consistently across a beach,” Johnston said. He explained that since the rover collects readings so frequently, it can capture small-scale variability like shadows cast by dunes. “And so, this system is able to move along and collect that data from essentially the level of a sea turtle approaching the beach and crawling out onto the beach.”

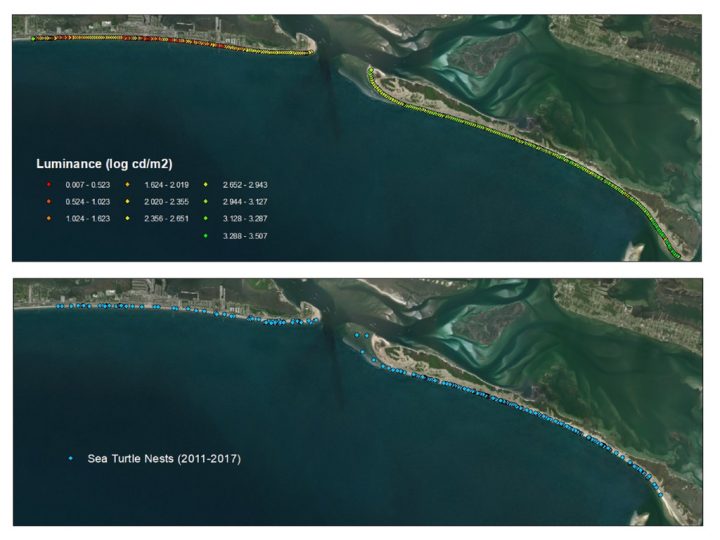

Back in the lab, Windle plotted the light measurements on a map. “I really wanted to make it visual,” she said. “I wanted people to look at a map and be like, ‘Oh, that’s where it’s problematic.’”

The three sites fell out as expected from bright to dark, but since Windle had collected high-resolution light readings, the maps revealed hotspots of light pollution along the coastlines.

Next, Windle used a mathematical equation to determine that there was a relationship between higher light readings and the distribution of sea turtle nests. In other words, darker spots corresponded to more nests.

Those results have prompted wildlife managers to rethink the relationship between turtles and light to focus on the nesting females.

“If it was darker, would we get more females who want to come there and nest?” Lamping asked. “We could potentially be missing out on nest opportunities because some turtles are deterred by the lights there.”

Shifting Policies

“Anna’s extraordinary research is just a starting point for using marine robotics and remote sensing for sea turtle conservation efforts,” Newton said in an email response. “The potential for drones is expanding daily … new platforms, new sensors, and new applications.”

“I would love for other beaches to use this type of technology to quickly and efficiently map out their problematic lights, because it just takes one night of doing this type of fieldwork and you get really highly accurate data,” Windle said.

After Windle shared her results with the Atlantic Beach Town Council, Mayor Cooper reported that the town has started considering new ordinances.

“We’ve looked at a lot of the other light ordinances in other towns to try to pull together what we could put in place for new development and redevelopment,” Cooper said. “The idea of our new ordinances is, to not necessarily make things less bright or less safe for people, but to structure the kind of fixtures that folks are using so that it focuses the light where it needs to be and doesn’t flood over in a way that would impact turtle nesting.”

Atlantic Beach supports the sea turtle volunteers and works with them to encourage residents to turn off lights when a nest is identified. “I think improving our lighting ordinances is the next step to make the beach even more turtle-friendly,” Cooper said.

With darker beaches in the works, the future for nesting sea turtles is looking bright.