PINE KNOLL SHORES — I guided my kayak down the wooden launch rails and into the shallow marsh waters at a dock behind the North Carolina Aquarium. As I stepped into the water, a small blue crab scurried away and quickly disappeared into the soft organic soil.

Nearby, a sea squirt attached to a dock piling and spit a stream of salty water in my direction. I settled into my kayak and set out in pursuit of two kayaks off in the distance heading west. With steady strokes, the blades of the paddle bit the water and pulled me nicely along.

Supporter Spotlight

As I glided past the suspicious eyes of royal terns and gulls roosting on an exposed grey sandbar, a laughing gull let a call with the drama of a steaming tea kettle whistle. I was quickly gaining on the paddlers ahead of me as they were not paddling with urgency, but rather with more deliberation.

Dr. Craig Harms, veterinarian and director of the Marine Health Program at North Carolina State’s Center for Marine Sciences and Technology in Morehead City, laid his paddle on the kayak rails and leaned forward staring into the screen of a smartphone. After a few seconds, he sat up, grabbed his paddle, spoke a few words to his companion and adjusted the course of their boats.

Alongside Harms, the other kayaker, Jason Eller, frequently raised a pair of binoculars and slowly scanned the surface of the water looking toward the shore about a hundred yards away. This navigator and spotter team was following a predetermined route in search of the only type of turtle that exists solely in the estuarine waters of North America, the diamondback terrapin. The men were participating in a citizen-science program that documents the location and abundance of this jewel of the marsh.

Mellissa Dionesotes, coastal wildlife technician with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, was also in the water, paddling east in her quest to find terrapins. She is charged with managing this program to get a handle on the health of this species in North Carolina. The program started five years ago with the help of the North Carolina Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve with 10 survey routes around Masonboro Island near Wilmington.

“The diamondback terrapin is a unique reptile that fills an important niche within our estuarine environment. It is vital that we understand its population density and distribution throughout North Carolina” said Dionesotes. “This monitoring project utilizes citizen science to answer these questions while engaging the local community in its conservation.”

Supporter Spotlight

This spring, two new routes were added in the marsh behind the aquarium when Carol Price, conservation research coordinator at the aquarium, partnered with the Wildlife Resources Commission to expand the research project.

“The aquarium wants to support protection of and promote appreciation for this beautiful at risk rare estuarine turtle,” said Price, who helped establish the search routes and put out the word to recruit enthusiastic kayakers with a keen eye.

The diamondback terrapin swims the brackish waters from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, along the East Coast to Florida and along the Gulf Coast to Texas. Named for the markings on the carapace, or hard upper portion of its shell, it has the most striking color of any turtle. The light grey skin color is painted with a unique pattern of black spots, lines, splotches and dots.

In contrast to their larger sea turtle cousins, these terrapins are small with the males having a 6-inch shell and the females reaching 10 inches. There are seven subspecies of the terrapin with two, the Northern and Carolina, occurring in North Carolina.

The diamondback terrapin is well adapted for its salty aquatic life. Unlike sea turtles, they don’t have flippers, but are still powerful swimmers utilizing their webbed feet, which can be pulled inside their shell. These terrapins can tolerate a wide range of salinity from almost fresh to ocean water. Their skin is capable of preventing the intrusion of salt and when salt does enter their bodies, it is removed by salt glands with little loss of water.

During periods of heavy rain, diamondbacks are also known to drink the freshwater that collects on the surface of the saltwater. At times they will even stick their head above the surface of the water and open their mouth in hopes of gulping a few raindrops. When salinity levels are high, they refrain from drinking until they can find lower levels.

Terrapins are vital to the health of the lush green gardens of smooth saltmarsh cordgrass throughout the estuary. Large colonies of periwinkle snails that live and feed among the grass can spread a fungal disease leading to bare patches of mud. Terrapins gobble up periwinkles like candy. Without terrapins, the periwinkle populations explode, resulting in the loss of valuable saltmarsh habitat.

Known as the “wind turtle,” the terrapins were once thought to possess supernatural abilities. Fishermen feared capturing a terrapin in their nets, believing it would then summon the storms to blow a gale.

Bones and shells of the terrapin have been found in Native American burial sites indicating that it is considered a sacred animal. Healers carried pieces of the shell in their pouches. Their culture includes fantastic stories about the “trickster” antics of the terrapin. Even though Native Americans held the terrapin in high regard, they also ate them.

Terrapin is an Algonquian word meaning little, edible turtle. Shells and bones of terrapins have been found in midden piles all along the Atlantic coast. Early Colonists learned from the natives that the terrapin was an important source of food. During the 1700s, terrapins were so plentiful and cheap that they were the dominant food that coastal plantation owners fed their slaves and servants. In Maryland, past records indicate that the monotony of eating terrapin day after day led to a law that restricted how often terrapin could be served.

During the mid-1800s, the humble food once fit only for slaves was now the food bon vivant of the elite. What was once considered trash fouling the nets of fishermen was now fetching high prices at the market. Terrapin soup and stew was the gastronomic hit at any celebration or wedding and was the food of presidents. Terrapins were being harvested by the thousands, by any means possible. Dogs were trained to sniff them out as the females came ashore to lay their eggs.

With demand high, terrapin populations began to tumble, threatening this important fishery. In 1902, the newly established Federal Fisheries Laboratory in Beaufort was tasked with raising diamondback terrapins to supplement wild populations. From 1909 until 1940, raising and releasing terrapins was the primary mission of the lab. However, during this time two events that rocked the nation played an important role in the future of the terrapin. Prohibition of alcohol from 1920-1933 eliminated a key ingredient from terrapin dishes. Without the amber-colored wine known as sherry, the now teetotaling soups and stews became passé. Then with money scares during the Great Depression this ritzy fare was too extravagant. Terrapins were still harvested, but the heyday of terrapin on the menu had passed.

Enough terrapins evaded the stew pot to keep the species swimming. However, the peril they face today presents a serious threat to their survival. Loss of salt marsh habitat, boat strikes, pet trade, road kill of nesting females, hardened shorelines, jewelry, the meat trade and entrapment in crab pots have contributed to declining populations.

Enough terrapins evaded the stew pot to keep the species swimming. However, the peril they face today presents a serious threat to their survival. Loss of salt marsh habitat, boat strikes, pet trade, road kill of nesting females, hardened shorelines, jewelry, the meat trade and entrapment in crab pots have contributed to declining populations.

Attracted to bait in crab pots, a terrapin will become trapped in the cage. Even though they can hold their breath from 45 minutes to a few hours, if the pot isn’t pulled to the surface in time, they will drown. They are especially vulnerable to “ghost” or abandoned crab pots that, if not removed from the water, will kill over and over.

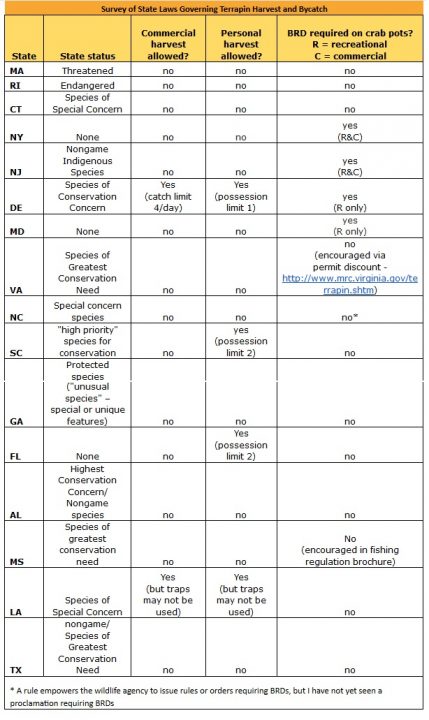

Only four of 16 states within the range of the terrapin require fishermen to use a bycatch-reduction device on their crab traps. These devices prevent the larger terrapins from entering the traps while still catching crabs. Popularity of the devices isn’t overwhelming, despite studies that indicate 70 percent of terrapins are unable to enter the traps, while the crabs can easily enter.

In North Carolina, the terrapin is listed as a species of special concern by the state and federal governments while the World Conservation Union listed it as a threatened species. Although listed as a priority species in the North Carolina Wildlife Action Plan, a guide for wildlife conservation, little funding is allocated for comprehensive research on the lowly terrapin. This is why the collaboration between the Wildlife Resources Commission, North Carolina Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve, North Carolina Aquariums and citizen volunteers is so important. Terrapins exhibit site fidelity, meaning that they are frequently found in the same areas or “hot spots.”

Dionesotes said she hopes to continue expanding the volunteer survey across the state and wants to hear from kayakers, boaters and fishermen on where terrapins are being seen.

As I paddled alongside Harms, I asked why he felt compelled to spend his time searching for terrapins. “If you have seen them, you want to participate in protecting this neglected, almost sea turtle,” he said.

To participate in the terrapin survey project or report terrapin sightings contact Dionesotes at mellissa.dionesotes@ncwildlife.org.