Second in a series on the Lower Cape Fear River Blueprint

WILMINGTON – More people, more development, more frequent and intense storms, and localized sea level risk – these are the pressures facing the lower Cape Fear River.

Supporter Spotlight

The river’s surrounding watersheds span more than 9,000 square miles and encompass more than 6,600 miles of streams and tributaries.

What happens in these watersheds directly impacts the river’s estuarine systems.To address head-on these issues that threaten the river’s vulnerable natural resources, the Lower Cape Fear River Blueprint, a collaborative planning effort being led by the North Carolina Coastal Federation, identifies four goals and strategies. Those goals include: protecting and restoring water quality; implementing living shorelines along the river’s banks; boosting oyster habitat; and protecting native coastal wetlands free of invasive species.

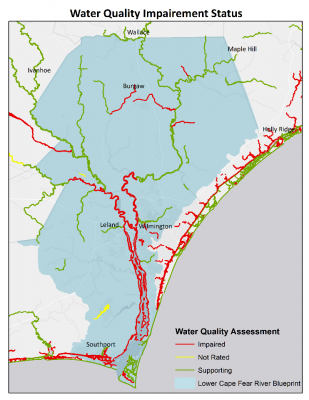

The First Goal: Water Quality

About $100 million to $120 million is spent each year in the Cape Fear River basin on fishing, hunting, boating and other natural resource related activities, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The North Carolina Division of Water Quality, or DWR, classifies all surface waters in the state.

Supporter Spotlight

A majority of the lower Cape Fear estuary is classified as SC, or waters identified as tidal salt waters for secondary recreational activities like fishing and boating where skin contact with the water is minimal.

Class SC is the least stringent water quality designation.

One of the objectives in the blueprint is to get the state to reclassify the waters between Carolina Beach State Park and Bald Head Island to SB, a designation that would make the waters primary recreation and provide the river an additional level of protection.

The process of getting that reclassification would entail petitioning the North Carolina Environmental Management Commission, or EMC, to a study how the river is primarily used. If the EMC rules to move forward with the request, the decision then goes to the North Carolina Rules Review Commission.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ultimately determines whether to approve the reclassification request.

Meanwhile, work could get underway to develop watershed restoration plans that call for reducing the amount of stormwater runoff flowing into the river.

The federation studied eight watersheds spanning more than 30,000 acres in Brunswick and New Hanover counties and determined that the current volume of runoff during storms can be reduced to levels recorded in 1993, according to the blueprint.

More than 600 sites have been identified as potential locations to reduce stormwater runoff throughout the lower Cape Fear River.

Runoff may also be reduced through wetlands restoration.

The federation has evaluated potential wetlands restoration sites to help restore and enhance the river’s water quality.

A study is underway to identify a list of restoration project sites with work in those areas to begin next year, according to the blueprint.

The Second Goal: Living Shorelines

The largest living shoreline project in North Carolina is underway along the banks of the Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson State Historic Site, a pre-Revolutionary port roughly halfway between downtown Wilmington and the mouth of the Cape Fear River.

The multi-million-dollar shoreline protection project combines the protection of reefmakers with the construction of a living shoreline.

As storms, changing tides and the brunt of waves created in the wake of shipping traffic ripped chunks of the historic shoreline away, fort officials decided to pursue a more natural way to combat erosion.

A major initiative of the federation is the education and implementation of living shorelines as an alternative to bulkheads, which can destroy wetlands and other habitat for marine life.

Living shoreline projects are built with various structural and organic materials, such as plants, submerged aquatic vegetation, oyster shells and stone. These projects generally work best along sheltered coasts such as estuaries, bays, lagoons and coastal deltas, where wave energy is low to moderate.

Mounting research shows that living shorelines hold up better through storms than hardened structures, enhance intertidal habitat for fish and other marine resources, and better defend against sea level rise.

In early 2017, the Army Corps of Engineers authorized its first nationwide permit for living shorelines, a move that solidified on a national level the value of living shorelines and helps streamline the permitting process.

Nationwide Permit 54, which became effective in March 2017, addresses the construction and maintenance of living shoreline projects.

The federation and researchers with the University of North Carolina Wilmington have identified areas of estuary shorelines in the lower Cape Fear River particularly vulnerable to erosion from commercial shipping traffic and effects from sea level rise.

That study revealed that Brunswick County’s shorelines along the river have suffered more erosion that New Hanover County’s river shores.

The federation is taking the results of that study to identify shoreline areas at the most risk for erosion.

The blueprint calls for pinpointing at least 10 potential living shoreline project sites within those areas and initiating funding and construction for those projects next year.

Next: Oysters and Invasive Species