This story has been updated.

RALEIGH — When test results show high levels of GenX or any of the other emerging contaminants not regulated by the federal government, does North Carolina have the authority to step in and regulate it?

Supporter Spotlight

The state’s ability to fill in the gaps in the federal clean water safety net has become one of the central points of contention as policymakers debate a way forward both in response to the GenX issue and in finding a way to regulate other emerging contaminants not covered under federal standards.

Last week, in a letter to the Environmental Protection Agency’s top regional administrator, four members of the Senate Select Committee on North Carolina River Quality Committee requested an audit of the state’s pollution discharge permitting and public water supply programs, as well as a clear ruling on whether the state has the authority to regulate emerging contaminants.

Sens. Michael Lee, R-New Hanover, Bill Rabon, R-Brunswick, Trudy Wade, R-Guilford, and Andy Wells, R-Catawba, sent a letter Jan. 23 to EPA Region 4 Administrator Trey Glenn saying the regulatory response by the state’s Department of Environmental Quality had raised questions, including the following:

- Does the Clean Water Act allow regulation of these compounds when there are no federal standards?

- What are the specific disclosure obligations of permit holders?

- What is the appropriate level of public involvement in settlement agreements regarding enforcement actions under the Clean Water Act?

The letter spells out specific guidance requested from the audits of the state’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, or NPDES, permitting program, including whether it gives North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality the authority to regulate emerging contaminants and chemicals not covered by existing state or federal standards. The senators also asked that the state’s Public Water Supply Program be audited to determine if it is meeting the requirements of the Safe Drinking Water Act and requests EPA guidance on emerging contaminants.

Law Center Responds

The senators’ letter prompted a response Tuesday from Southern Environmental Law Center Senior Attorney Geoff Gisler, who copied EPA Region 4 and DEQ officials, saying that burdening DEQ with an audit at this point would hurt the department’s ability to deal with water pollution and contamination. The department has experienced years of cuts in water quality positions, Gisler noted, and he called for passage of a House bill approved unanimously last month that was not taken up in the Senate.

Supporter Spotlight

The bill would have increased DEQ’s budget to cover GenX and emerging contaminant testing and studies. In his letter, Gisler disagreed with the senators’ position, pointing to a backlog that has reduced the turnaround time for NPDES permits to as much as two years.

“The understaffed agency needs additional funding to address the protection of water quality, in particular, the backlog of existing water quality (“NPDES”) permits and the contamination of drinking water sources from unstudied chemicals,” Gisler wrote. He also asserted that the state does indeed have the authority to regulate compounds not covered by existing federal standards.

The law center and a coalition of environmental groups have pushed for an array of statutory changes that would clarify state law on the authority to set up regulatory frameworks beyond federal law.

The debate over limits of state environmental regulation has a long history in North Carolina. A comprehensive five-year review of all the state’s roughly 19,000 rules, with a priority on the state’s environmental frameworks, started in 2013 with a key requirement that all state agencies break out rules without any federal analog. Those rules are being subjected to closer scrutiny during the review process.

A year after that program was passed the legislature also approved an updated version of the Hardison amendments, laws that prohibit state regulations from being more stringent than their federal counterparts.

Environmental groups have called for the repeal of the amendments, named for a former senator, Harold Hardison, D-Lenoir, who pushed the original legislation in the 1970s, saying it takes away needed flexibility for state regulators to address pollutants such as GenX and cements in place only minimal levels of protections.

Funding Disputes Unresolved

In addition to policy questions, the legislature will have to settle a dispute over funding for DEQ and as well as for the Department of Health and Human Services.

Last month, the Senate walked away from a House proposal that won unanimous approval. House Bill 189 would have provided DEQ an additional $2.3 million funding with the bulk of the money going for a high-resolution mass spectrometer, an analytic instrument for more timely and cost-effective evaluation of the threat to public health and safety from discharges of GenX and other emerging contaminants, and to hire and train five scientists for a new sampling and testing operation.

Senate leader Phil Berger criticized the proposal at the time, saying the state should be able to continue working with EPA labs for testing and use existing funds for the testing programs.

The most recent House and Senate differences are part of a long-running disagreement between the two chambers on DEQ spending. The two sides went into budget discussions last year with wildly different proposals on cuts to personnel at the department. This year, during the upcoming short session, they will have to come to agreement again on a spending plan with the cost of implementing a strategy on emerging contaminants adding an extra layer complication.

GenX Levels Spike; Lawsuit Announced

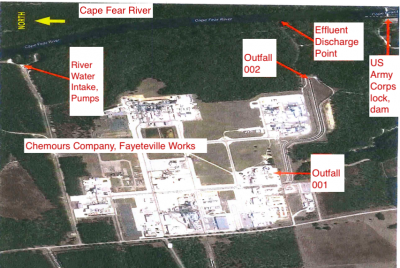

Thursday, during a community meeting in Bladen County near the Chemours plant that produces GenX and other compounds, DEQ officials detailed another significant increase in GenX levels in the Cape Fear River from sampling near the plant after a heavy rain.

Testing at the Chemours outfall showed the spike on Dec. 11 sent GenX levels to 2,300 parts per trillion, well over the state’s health goal of 140 ppt. Tests showed levels the next day at the outfall at 68 ppt.

DEQ spokesperson Bridget Munger said studies are being conducted to assess the causes.

“DEQ is looking at all possibilities to determine what may be causing elevated levels of GenX following rain events. As part of the department’s assessment of the entire site, soil samples have been taken. We expect to have the results next week,” Munger said.

On Wednesday a complaint was filed by attorneys in a class action lawsuit charging that Chemours and DuPont hid the dangers of GenX exposure from regulators. The complaint, part of a class action suit that began last fall, also seeks more information of the possibility of air dispersal of GenX. The companies have requested that the suit be dismissed.

Earlier this week, the state Science Advisory Board reviewed the methodology used by DHHS in determining the state’s health goal of 140 ppt. The board agreed last month to take on the review to determine if goal was reasonable given the available science on GenX. At its most recent meeting Monday in Raleigh, the panel moved forward on its review, but took no action.

Recent movement on GenX testing also took place outside the state. In a Jan. 11 letter from Kate McManus, EPA’s acting director for water quality, Chemours was ordered to begin well water testing around its Washington Works facility in West Virginia. The letter, which concerns about GenX levels revealed in well tests near Chemours plant near Fayetteville, gives the company until March 31 to complete the testing.

DEQ also released a map of the area around the plant with information on prevailing wind currents, part of an effort to determine the extent of GenX that resulted from air releases either of the compound itself or a related compound that becomes GenX when it comes in contact with moisture.

The investigation by DEQ’s Division of Air Quality began when well tests near the site, but upgrade from possible groundwater sources showed high levels of GenX.

The model, known as a “wind rose,” for the Fayetteville area shows a predominate wind direction of southwest to northeast.

According to an update prepared for the meeting Wednesday in Bladen County, there have been 505 wells sampled by DEQ, Chemours or a third-party contractor. Of those,148 showed no detection of GenX, while 151 of the wells tested showed levels of GenX that exceeded the state’s health goal of 140 ppt and 206 wells with levels below the health goal. DEQ is reviewing a proposal by Chemours to install activated charcoal filters for homes with contaminated wells.

Chemours began another round of testing began last week expanding the sampling radius around the plant to 2.5 miles. DEQ is also conducting tests on fish taken from Marshwood Lake, which is roughly a half-mile from the Chemours facility.

As part of the investigation into groundwater concerns, DEQ’s Division of Waste Management has directed Chemours to conduct a full site assessment.