When visiting the state’s coastal counties, beaches and scenic views are usually the focus. But there is also an underlying history at these tourist destinations. Many of these sites play a role in the events that have shaped black culture. This American history — from slavery to civil rights — is mirrored along the coast. As Black History Month draws to a close, here are a few places where we can better understand the difficulties and celebrate the successes of African-Americans in North Carolina.

Dismal Swamp

Archaeologists are still learning details about how hundreds, or even thousands, of slaves escaped to and lived in this inhospitable mix of mud, insects and vegetation. But they do know that this swamp was part of what’s known as the Maritime Underground Railroad that existed in the 1800s until the Civil War. A slave born in Camden County around 1786 wrote about his experiences working on cargo vessels in and around these waterways — and how he eventually obtained his freedom and saved enough money to buy his wife and children — in his “Narrative of the Life of Moses Grandy; Late a Slave in the United States of America.”

Supporter Spotlight

Chowan County Courthouse

Harriet Jacobs, who was born into slavery but eventually escaped and wrote one of the first narratives from the perspective of a female slave in the South, is a significant historic presence in this coastal town on the Albemarle Sound. Visitors can learn more about her time in Edenton though a walking tour. It’s self-guided much of the year, but in February, docent-led tours are available Tuesday through Saturday to more fully explore her history, said Natalie Harrison, program coordinator for the Historic Edenton Historic Site. There are 13 stops, including the building that was built in the 1760s, where Jacobs’ grandmother, Molly Horniblow, was granted her freedom. Horniblow played a significant role in sheltering Jacobs and her children.

The Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony

This site was occupied by Union forces in 1862. With the Emancipation Proclamation the next year, the slaves were given a new start and a taste of freedom. During the following years, the colony continued to grow despite what was at the time an isolated location west of Nags Head. By 1864, records show that it had become a thriving African-American community with 561 houses built on the island and a population of almost 4,000. Many of the residents fought for the Union during the Civil War. Afterward, though, the population dwindled as residents left to begin new lives elsewhere, according to information from the Fort Raleigh Historic Site.

The Isaac J. Smith House

This property at 607 Johnson St. in New Bern was built in 1922 as the home of Smith, a realtor, finance broker and one of the area’s wealthiest African-Americans. He also served in the North Carolina House of Representatives in 1898. The site is one of the homes, churches and businesses on the African-American Heritage Tour in New Bern, which was a popular town for both slaves and freed blacks during Colonial times and over the years grew into a community with a sizable black population of skilled craftsmen and sailors. Close to the Smith house, for example, is the former Rhone Hotel at 512 Queen St., a business owned and operated by African-Americans, and home to Charlotte Rhone, the first black registered nurse in the state.

Hammocks Beach State Park

Bear Island, which is now a part of this coastal park near Swansboro, was a favorite place of Dr. William Sharpe, a New York physician, during the early 20th century. John Hurst, an African-American guide, often accompanied him and eventually became his friend. While Sharpe wanted to leave the property to his guide, Hurst convinced him to leave it to the North Carolina Teachers Association, an organization of African-American teachers, who eventually donated the island to the state with the intention of creating a park for minorities. It opened for all following the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Ocean City

Beach communities that catered to African-Americans can be found dotted along the North Carolina coast. This historic section of North Topsail Beach is one of them. Established in 1949, it’s thought to be one of the first owned by African-Americans. It was envisioned and developed by Wade H. Chestnut Sr., an African-American, and white Wilmington attorney Edgar L. Yow. Recently, several street signs were dedicated at the site to preserve its historical significance.

Supporter Spotlight

Airlie Gardens

Minnie Evans, who was born in Pender County, worked for years as the gatekeeper at this public garden near Wrightsville Beach. She gained fame, though, through her work as a visionary artist. Although she had no formal training, it’s said that she began to paint in 1939 when she had a prophetic dream. And her work is described as dreamlike and fantastical. She often painted at Airlie, using whatever materials were handy, and was inspired by the natural beauty. Her work was eventually shown in New York’s Whitney Museum and the North Carolina Museum of Art. Now the gardens are home to the Bottle Chapel, designed by Virginia Wright-Frierson, as a commemoration of her art.

Bellamy Mansion Museum

Not many historic sites fully explore African-American traditions, but this 1860-era site at 503 Market St. in Wilmington was constructed largely by both free and enslaved black artisans. Gareth Evans, executive director, also said they’ve made an effort to restore the slave quarters in the northeast corner of the property, to show the day-to-day lives of the Bellamy house servants, including a cook, a nursemaid and a butler. The Museum and the City of Wilmington also collaborated on A Guide to Wilmington’s African-American Heritage that lists 37 historic, religious, educational, social and cultural sites.

1898 Memorial Park

“There are many sites here that represent the coup, the successful coup, of 1898,” said Islah Speller, founder of the Burnett-Eaton Museum Foundation in Wilmington. Those events were intended to threaten the black community. In the process, dozens were killed or wounded and much of the city’s black leadership was banished. The effects were also felt on several black-owned businesses. Speller offers walking tours of these sites by appointment, as well as those that focus on other aspects of African-American history in and around Wilmington. This memorial at 1081 N. Third St. was designed by Atlanta sculptor Ayokunle Odeleye and dedicated in 2008.

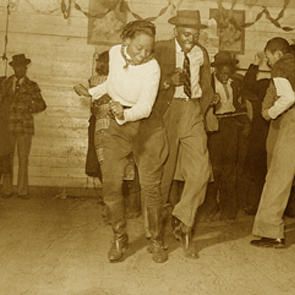

Freeman Park

What’s now a popular spot on Pleasure Island near Snow’s Cut was once known as Seabreeze or Freeman’s Beach. It has a long history, but from the 1920s to the ’60s it was a well-known beach resort for African-Americans, with hotels, restaurants and an amusement park with Ferris wheel. The music clubs, or jump joints, drew so many popular and well-known performers that the resort earned the nickname “Bop City.”

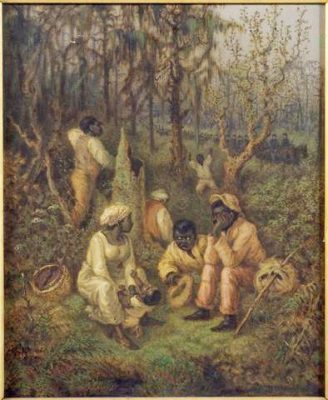

Navassa

The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, extends through South Carolina and Georgia but it’s northernmost sites are along the sea islands and coastal areas of North Carolina. The culture is distinguished by the creole language spoken by the Gullah and Geechee people and the many lingering influences of their African heritage. Navassa, which was one home to five rice plantations, in one of the North Carolina communities has strong ties to the culture. Efforts are underway to preserve this past and create a Gullah Geechee resource center there.