BEAUFORT — “It’s time to fish or cut bait,” if the world truly wants to save the North Atlantic right whale from extinction, Doug Nowacek said recently.

Nowacek, a whale and marine acoustics expert at the Duke University Marine Laboratory in Beaufort, was reacting to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s recently completed North Atlantic Right Whale Review.

Supporter Spotlight

The review released in October paints a grim picture for the survival of one of the world’s most majestic and endangered species – there are by all reputable accounts fewer than 500 of them left on the planet.

Nowacek paints it even a bit more grimly.

While NOAA’s review states that the most recent population is about 458 whales, up from around 270 in 1990, it also notes a steady decline from an estimate of 483 in 2010.

But the numbers look worse if you dig deeper, Nowacek said. For example, 18 right whales are known to have died this year alone, 12 in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence. There have been only five known births.

That, Nowacek said, is more than three times more deaths than births, an unsustainable rate for any species.

Supporter Spotlight

“The females used to have a calf roughly every three years, maybe two if there if they are healthy, maybe four if there are more stressors,” he said. “Now that’s up to six or seven.”

The, whales, which can reach 158,000 pounds and 50-55 feet long, are generally thought to live up to 50 years, “but more and more of them are dying in their 20s and 30s,” mostly from ship strikes and entanglement in nets, Nowacek said.

Since the whales generally take 10 to 20 years to reproduce for the first time, that means many of them are only having 10 to 20 or so years in which to reproduce. If you assume that roughly half of the right whales are generally male, there’s already a very limited pool. And Nowacek pointed to a paper published this past summer by Richard M. Pace, Peter J. Corkeron and Scott D. Kraus, which states that their study found “reduced survival rates of adult females relative to adult males.”

In both 2010 and 2011, there were estimated to be 200 females in the species, declining to 186 in 2015, according to the paper. Males declined from a peak of 283 in 2010, to 272 in 2015.

The researchers’ conclusion is that, the “population has not been rebounding well in recent decades, and our analysis raises concern that the slow recovery has stopped or even reversed.”

Kraus is vice president, senior adviser and chief scientist for marine mammals at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium in Boston. Corkeron and Pace are NOAA employees, and the study was done for NOAA.

Nowacek also noted that right whale deaths have exceeded PBR, or potential biological removal, for at least 20 years. PBR is a fishery management term defined by the Marine Mammal Protection Act as the maximum number of animals, not including natural mortalities, that may be removed from a marine mammal stock while allowing that stock to reach or maintain its optimum sustainable population.

So, less time to reproduce, longer times between calving, fewer females, a long time to reach reproductive age and accidental deaths that exceed PBR. It’s not a good situation.

Nowacek says he appreciates NOAA’s review and its recommendations, including the following:

- Designating a right whale recovery coordinator in the Greater Atlantic Region to focus efforts on recovery. Diane Borggaard, a biologist with 20 years of experience in species recovery, is taking on this role.

- Convening a new Greater Atlantic Region North Atlantic Right Whale Recovery Team, a group of experts in whale research and management that will coordinate closely with the Southeast Region’s Implementation Team.

- Collaborating with U.S./Canadian working group to reduce ship strikes and fishing gear entanglements, two of the largest human-caused threats to right whales. NOAA has already held several meetings with counterparts in Canada to discuss gear modifications, gear markings and ship-speed regulations.

- Convening a work group with Canada to focus on addressing the science and management gaps that are impeding the recovery of North Atlantic right whales in U.S. and Canadian waters. The group’s first meeting was held in September.

- Reinitiate the fisheries biological opinions under the Endangered Species Act in light of new information on right whale biology that may reveal effects of the fisheries that may not have been previously considered in the original biological opinions.

Nowacek doesn’t think right whales have a lot of time for “convening” and “re-initiating.” They need action now.

NOAA’s report includes the following recommended actions:

- Developing a strategy for understanding stressors on right whales, including the effect of chronic, sub-lethal entanglement on overall and reproductive health and the effects of changes in environmental conditions and prey availability.

- Developing a long-term, cross-regional plan for monitoring right whale population trends and habitat use.

- Prioritizing funding for a combination of acoustic, aerial and shipboard surveys of right whales that can be used to understand right whale presence in near real time.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan and the Ship Speed Rule to determine whether it may be necessary to modify or extend these protections.

- Reviewing the effects of commercial fishing operations on right whales.

But, Nowacek noted, those “ing” words are there again: “Developing.” “Reviewing.” “Evaluating.”

“I know NOAA is trying, and everyone appreciates that,” he said. “But I think it’s important to keep holding NOAA’s feet to the fire.”

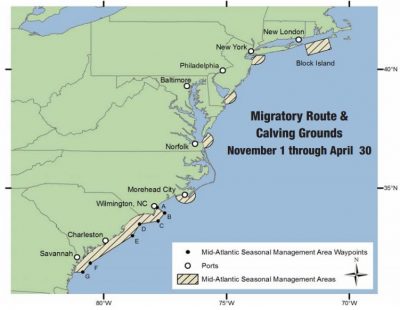

Ship-strike deaths of right whales have declined in recent years, he said. That’s largely a result of a 2008 federal rule that requires large ships to travel at speeds of 10 knots or slower, seasonally, in areas where right whales feed and reproduce, as well as along migratory routes in between.

But net entanglement is an issue that doesn’t require more study.

“We need to get the gear out” of waters, particularly at times when we know right whales are likely to be there,” Nowacek said.

According to an article by Ann Hui in The Globe and Mail, a Canadian newspaper, it was about four years ago when fishermen started seeing right whales off the coast of Cape Breton Island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. It was about the same time that fishermen and others in the Bay of Fundy had stopped seeing right whales there.

“With each summer came more sightings,” according to the article. “The sightings were initially treated as a passing curiosity. But then came the deaths. That’s when everyone started paying attention.”

Reports indicate there were close to 120 right whales in the gulf this summer. That means 10 percent of those there died. And that represented 2.6 percent of the entire estimated population. If you take 18 as the number – U.S. and Canada – that’s almost 4 percent of the population.

The first dead whale was discovered in the first week of June. Five more were found that same month, and more as the summer went on.

In the second week of July, the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans, or DFO, announced a temporary closing of fisheries in one small area of the gulf. Eventually, it just shut down a huge swath of the gulf for the rest of the deep-water snow crab season.

According to the article, a report eventually detailed the cause of death for six of the whales: Four died from vessel strikes and one from a long-term entanglement in fishing gear. A sixth was also believed to have died from a ship strike, but it was too decomposed for complete confidence. But there were other entanglements, too, at least four, although two were disentangled.

The necropsies showed no evidence of bio-toxins, infectious diseases or starvation in the whales.

In August, Transport Canada set temporary speed limits of 10 knots for large vessels of 20 meters or more in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and it was to remain in place until the whales moved on, most likely this month, when they normally start heading south into U.S. waters. Some reportedly have been seen off North Carolina, though Nowacek isn’t sure they’ve been accurately identified.

Canadian fishermen are obviously concerned, particularly those in fixed-gear fisheries, involving traps and lines left in the water unattended for a long period of time.

According to the article in The Globe and Mail, fishermen in the Gulf of St. Lawrence might be able to learn from the experience of the watermen in the Bay of Fundy.

“In most years, the whales migrate south by October,” according to the article. But in 2006, the whales remained in the Bay of Fundy well into November, and DFO threatened to implement full closings just as the lobster season was about to get under way. Working together with the federal department, the local fishing industry was able to put in place a series of policies to avoid whale interactions and also avert closings.

An important part of this was setting up a hotline for fishermen to call each day before heading out for information on whale sightings and locations. Education campaigns for local fishermen focus on what to do when they see a whale.

Canadian fishermen have also been researching the effectiveness of new equipment designed to avoid such entanglements.

Nowacek said that’s a good thing, and it’s happening in the U.S., too. But, he noted, bureaucracies like NOAA don’t move quickly to allow new gear or significant gear modification. And time is of the essence for the right whales.

Shippers have been helpful, and fishermen, including lobstermen in the Boston area, have proposed changes, he said. Many want to help. But, again, “Right whales don’t have a lot of time.”

Nowacek also emphasized that the problem is only getting more complex. Even during the brief population rebound earlier in 2002, no one he knows in the scientific community thought it was “solved.”

One of the complexities is that it’s hard to know for sure where the right whales are going to go, and the routes they will use to get there, as the disappearance from the Bay of Fundy and appearance in the Gulf of St. Lawrence shows.

And, Nowacek said, during the long debate in the Obama administration over seismic testing for oil and gas reserves and drilling for oil and gas off the East Coast, he and many other leading marine mammal scientists pointed out that the testing and drilling could be horrible for the remaining right whales, disrupting their migration routes, feeding and reproduction.

The Obama administration put the East Coast offshore waters off-limits to drilling, and didn’t give permits to companies that wanted to do the seismic testing. But the Trump administration has revived those goals for the waters off the South Atlantic, including North Carolina.

Meanwhile, new acoustic research shows that right whales are offshore from North Carolina to Georgia, not just in the depths of winter, but nine months a year. That magnifies the risk right whales face from oil and gas development.

Climate change is another risk factor. Some have said that’s why there were so many right whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence this summer. Historically, they have generally started the spring in Cape Cod Bay of Massachusetts, then summer in the Gulf of Maine and the Bay of Fundy before heading south. The Gulf of St. Lawrence is pretty far north of that range.

NOAA, in its announcement of its five-year review of the right whale population, recommends that the species continues to be listed as endangered and confirms the risks.

“We identify the most significant need as reducing or eliminating deaths and injuries from human activities, namely shipping and commercial fishing operations,” according to NOAA. “The second priority is to get better data on their population trends, distribution and health, as well as on their habitat needs and uses. The third priority is to study the other potential threats, such as habitat degradation, noise, contaminants, and climate and ecosystem change, and determine ways to address them.”

Again, Nowacek praised NOAA for its assessment and for concluding that the right whale should remain on the endangered species list.

It all, he said, “Looks good on paper.” But looking good on paper might not be enough.