Editor’s Note: Coastal Review Online is now featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski. Cecelski writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

Recently he made the trip to Denver, Colorado, where he surprisingly found while visiting the Western History Collection at the Denver Public Library, manuscripts about his special interest: the history of the North Carolina coast. Blackbirds at Big Island is another essay Cecelski wrote using research from his trip to Denver.

Supporter Spotlight

DENVER, Colo. — At the Denver Public Library’s Western History Collection, I also found an even more surprising set of documents bearing on the history of the North Carolina coast — a collection of letters and maps from the 1930s that provide insight into the origins of some of our most beloved coastal wildlife refuges.

I found them in a collection of papers that had belonged to John Clark Salyers, a U.S. Department of Agriculture biologist who is remembered as “the father of the national wildlife refuge system.”

Salyers joined the USDA’s Office of Biological Survey in 1934. Embracing Aldo Leopold’s principles of wildlife management and environmental ethics, he spearheaded the creation of our first national system of waterfowl refuges.

On his watch – he did not retire until 1961 – the national wildlife refuge system would grow from 1.5 million acres to almost 29 million.

In 1940, his office was moved to the Department of Interior and became part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Supporter Spotlight

When he began the job, Salyers traveled across the U.S. in search of new sites for inclusion in the nation’s young system of wildlife refuges. One report said that he drove 18,000 miles and laid out plans for 600,000 acres of new wildlife refuges in his first six weeks on the job!

The Birth of NC’s Coastal Wildlife Refuges

The timing was right. First, the U.S. Congress had just passed the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act in 1934—so there was money to purchase land for waterfowl conservation.

Second, there was political support from the White House. President Franklin D. Roosevelt personally advocated for a national system of wetlands conservation that would help migratory waterfowl recover from decades of overly zealous sport hunting and market gunning.

Third, America was in the middle of the Great Depression and land was cheap.

On the N.C. coast, timber mills had been shutting down since the stock market crash in ’29 — demand for lumber, shingles and other wood construction products had plummeted.

Large tracts of forest, swampland and marsh had grown practically worthless. In some cases, landowners pleaded with better-off neighbors, if they could find any, to take their land for pennies.

Sometimes they even offered to give away their land. They simply wanted to be free of the obligation of paying the property taxes.

You can see this in Salyers’ papers. As soon as Congress allocated funds for waterfowl habitat, large landholders began to offer to sell land to his office.

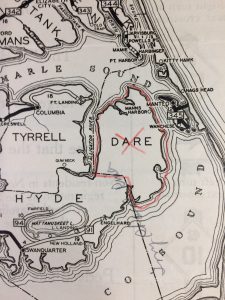

The Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. of Boston, for one, repeatedly approached Salyers about selling the company’s 175,000 acres of swamp forest on the mainland of Dare County.

That vast wilderness (albeit honeycombed with abandoned timber camps) eventually became the bulk of the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, to me one of the state’s great natural wonders.

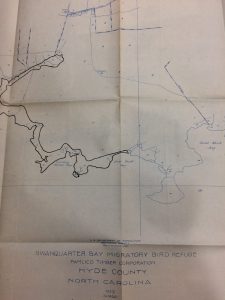

I found similar letters from the Pamlico Timber Co. It was one of several New York and Pennsylvania lumber companies that had bought land on the N.C. coast during the great timber boom that lasted roughly from 1880 to 1920. The company’s president offered to sell a sizable part of its holdings in Hyde County.

Those salt marshes and lowlands became the Swan Quarter National Wildlife Refuge, another of the state’s natural treasures.

The Civilian Conservation Corps

Fourth, and finally, the availability of Civilian Conservation Corps labor was also important. The Civilian Conservation Corps, one of Roosevelt’s “New Deal” agencies, aimed at providing the unemployed and underemployed with meaningful jobs.

Times were very hard on the Outer Banks. If there was a local family that did not benefit from the CCC, I have yet to hear about them.

During the Great Depression, CCC laborers built roads, bridges and miles of sand dunes on the Outer Banks. They undertook mosquito control projects, too, as well as many other projects that later made it possible for the Outer Banks to become a popular tourist destination.

Critical to our story today, CCC laborers also built the elaborate system of waterfowl impoundments, canals, ditches and floodgates necessary for creating and managing the new wildlife refuges.

The letters in Salyer’s collection at the Denver Public Library clearly show that local and federal planners counted on the availability of CCC labor to create the kinds of habitats that would provide good feeding grounds for migratory ducks, geese and swans.

Frank Stick and Hatteras Island

To me the most exciting item in Salyer’s collection is a June 14, 1934, letter from Frank Stick.

In the letter, Stick is proposing — I believe for the first time — what will become the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, one of the glories of North Carolina’s Outer Banks.

The letter is to Salyer’s boss at the Office of Biological Survey, J.N. “Ding” Darling, and is written on Stick’s stationery as head of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration’s transient camp at Nags Head.

Stick proposed that the Office of Biological Survey purchase a long stretch of Hatteras Island running from Oregon Inlet to the north side of Rodanthe for inclusion in the national wildlife refuge system.

“As you know,” he wrote Darling, “the area is in the center of what is probably the greatest concentration point for waterfowl in the entire East; in fact, the greatest I have visited in these United States, and I am familiar with most of the famous wildfowling sections of this country.”

Before moving to Roanoke Island in the 1920s, Stick had been a successful outdoor artist, with his work appearing in magazines like the Saturday Evening Post and Field and Stream. He was also an avid fisherman and had traveled widely across the U.S. on fishing trips.

In fact, he had first visited the Outer Banks on a fishing trip with the famous Western novelist Zane Gray.

The Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge

In the letter, Stick described the part of Hatteras Island that he had in mind for a wildlife refuge:

“The entire property under advisement extends for about twelve miles north and south, with that amount of ocean frontage and some fifteen to sixteen miles of sound frontage. There are a number of small creeks and ponds, which, through the use of the CC camp … may be greatly improved … It contains by estimate four thousand acres, and including the water area extending to the channel … would make a sanctuary of some sixteen thousand acres. This would include all those reefs, flats and natural feeding grounds of our ducks, geese and brant, in that territory.”

He also wrote:

“One of the great advantages of the location tentatively fixed upon is that it will not interfere with the public and is free of inhabitants, excepting for the Coast Guard stations. It is unquestionably a beautiful layout. I personally own several valuable shooting islands in this area and two tracts of beach land, which I will donate freely, if this is desired.”

Stick was apparently right that nobody resided on that part of Hatteras Island. However, he may not have fully explained the ways that local people used the area’s beaches and marshes.

Historically, Hatteras Islanders had used that part of the Outer Banks for commercial fishing, market gunning for waterfowl, livestock grazing and farming — and that reality, along with the federal government’s creation of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore in 1937, inevitably had an impact on the islanders and, in some cases, led to deep bitterness.

I must confess though: I grew up just south of the Outer Banks and from my childhood until now, I have made many a trip to the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge.

My wife — the truly incorrigible birder in our family — has dragged me over Pea Island’s waterfowl impoundments’ levees and down into its marshes on blustery and frigid winter days many a time.

And afterward, when we’re warm and toasty again, I am always grateful to her. And I know that I will never forget the beauty of those wetlands or the awe inspiring flocks of snow geese, tundra swans and other migratory birds that we have seen there over the years.

I will also not forget that things could have turned out different. The great flocks could have disappeared, the marshes could be gone, and the public’s right to wander among the dunes could have vanished. The peace and tranquility of that part of Hatteras Island could have been a distant memory.

That would almost certainly have been the case if not for John Clark Salyers, local conservationists such as Frank Stick, a Congress and a president that believed in wetlands conservation, and the hard work of the local fishermen and other islanders who went to work for the CCC.