Update April 23, 2018: Study Recommends State Park on Black River

First in a three-part series.

Supporter Spotlight

BLADEN COUNTY – Roughly at the halfway mark of the Black River, some of nature’s old treasures reach up through the water and tower over the remote swamp where they’ve grown for centuries.

The trunks of the ancient bald cypress trees here are hollow, knotty and gnarled, a visual testament to their age.

Their roots, or “knees” as they’re called, pepper the spaces between the trees throughout the swamp. Hundreds of these knobby, stalagmite-like knees, some 4 to 5 feet tall, jut from the water.

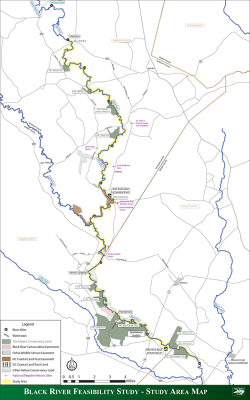

This is the Three Sisters Swamp, a majestic area of the Black River, which widens and narrows, curves and turns for about 70 miles from its beginning at the confluence of Great Coharie Creek and Six Runs Creek in southern Sampson County to where it empties into the Cape Fear River some 14 miles north of Wilmington.

Three Sisters Swamp, given its name because of how the swamp exits via three distinct channels into the river, showcases some of the more than 1,000-year-old trees thriving within the Black River.

Supporter Spotlight

In the 1980s, while conducting research tying cypress tree ring growth to studying the history of climate change, University of Arkansas Professor David Stahle discovered the Black River to be home to some of the oldest living trees in the world.

One of the trees cored and tagged is 1,654 years old “and counting,” according to Stahle.

“That’s a core sample I took in the mid-1980s,” he said in a telephone interview. “I took it 15 feet above the ground so that’s the minimum age of that tree. We believe there are much older trees in there. We don’t really know yet.”

Since that discovery, conservation and environmental groups, with the help of some private property owners, have taken steps to protect more than 14,000 acres, according to The Nature Conservancy.

Now, much to the ire of many riverfront private property owners, the Division of Parks and Recreation is considering buying land owned by the conservancy around the river.

Steamboat Alley

The Black River has a history as rich as its tea-colored water.

Long before paddlers enjoyed the quiet, scenic views of mostly undeveloped riverfront land here, the river was a passageway for transporting people and goods.

Settlers in the 1700s began using flats or pole boats in the river. Before that, modern-day paddlers like to point out, Native Americans navigated the river in canoes.

Following the Civil War, technological advances introduced the use of shallow-draft steamboats on the Black River.

In an effort to encourage area trade, the Black River Navigation Co. was formed in the mid-1870s. With the assistance of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the river was dredged to make an accessible steamboat route.

Steamboats hauling everything from lumber and wood products to cotton, rice and livestock ferried back and forth between Wilmington and Sampson County’s Clear Run community, which was the head of navigation on the river.

Naval stores, or materials used to build and maintain ships, and lumber were the primary cargo of steamboats navigating the Black River between 1875 and 1914.

One of the largest steamboats that traveled the river was a 57-ton stern-wheel named the A.J. Johnson.

According to the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, the steamer was built at Clear Run in 1899 and operated until it sank where it was tied up in Clear Run during a storm in 1914.

The steamer’s hull remains at the river’s bottom, as does an intact pole boat farther downriver in Bladen County.

The River and Research Today

Hints of the river’s past lie in the few remaining steamboat landings on private property.

It’s hard to imagine large steamboats navigating the river with its undulating width and depths. Large branches and entire fallen trees clog the river, making even kayaking or canoeing tricky.

As the river has been allowed to return to its more natural state, its water quality has improved since its days as a navigable body.

Though, as one vigilant riverkeeper points out, runoff from hog farms along the upper part of the river in Sampson County are a source of pollution, the Black River is designated outstanding resource waters.

The river received that classification in May 1994 from the then-North Carolina Department of Natural Resources, now the Department of Environmental Quality.

The riverfront itself remains mostly undeveloped.

Much of the privately owned land along the river is rural landscape dotted by farms of row crops and blueberry fields, seemingly far away from river’s banks, from the river’s view.

During a mid-August trip from Arkansas to the river, Stahle and a group of graduate students traversed the swampy forest to core, tag and map the locations of the ancient trees.

Their locations and size, which Stahle describes as “massively buttressed trees,” make them a challenge to core.

“You have to actually climb the tree and get to a third of the way up to get the solid wood and even then it’s not solid in many cases,” he said.

For that reason, he and the group of student researchers were selective in choosing the trees they cored, looking for the oldest they could find.

In all, they only cored about 20 trees in a week.

“It’s far from efficient, what we’re doing,” Stahle said.

The core samples are being used by researchers in two ways: The samples reveal the ages of the trees and they provide a window into the history of climate change in the region.

Cypress trees form very distinctive concentric growth bands, Stahle said. These bands can be counted, starting with the outermost ring, and dated to the calendar year.

“Then, if you look at those rings, they have an amazing variability of width from one year to another,” Stahle said. “What’s going on there is climate is affecting tree growth. In moist years, they grow well. In dry years, they grow poorly. You can use that climate-induced pattern of ring variability to synchronize going back hundreds of years in time.”

The history of drought and moisture variability, he said, reveals drought conditions during Colonial times.

In 1587, the year Virginia Dare was born and Sir Walter Raleigh’s colony last seen, tree ring widths indicate it was the driest year in 800 years, Stahle said.

There’s been an increase in wetness in eastern North Carolina since the 17th century and into the 21st century, although not a dramatic change, he said.

“This is very valuable for dating past climate,” Stahle said.

Stahle’s research has him returning to the Black River, but “not enough.”

“We’re really just scratching the surface,” he said. “These streams contain not only living trees, but (also) dead wood that litter the forest floor and are often submerged when the water’s high. Some of those logs are so-called storm logs that simply fell over and sank to the bottom of the creek and maybe have been there for 10,000 years. We’re trying to map those areas that are left. Some of them are privately owned. Some are public properties. On those public properties we don’t know necessarily what’s super ancient. If we can provide those agencies with the specific information, it may assist their management efforts going forward.”