RALEIGH — The long-troubled Neuse and the Cape Fear rivers are in the headlines again, joining nine others in the advocacy group American Rivers’ annual list of the nation’s most endangered systems.

The listing of the two North Carolina rivers is mainly, according to the report, because of threats from agricultural operations. But a program that made a positive difference in the rivers’ health after Hurricane Floyd two decades ago could offer similar hope as the region continues to recover from Hurricane Matthew’s destruction in 2016.

Supporter Spotlight

Like others on the American Rivers list, the two rivers are highlighted this year not just for environmental challenges, but also because of critical public policy choices. Despite disagreement with the organization’s assessment, this much is indisputable: A spate of pending decisions could have big effects on water quality.

There are numerous decision points ahead as policy makers plan the next steps in the ongoing recovery from Hurricane Matthew and map out a new course for management of both watersheds.

Supporter Spotlight

During the past year, environmental committees in the North Carolina General Assembly have been struggling with how to rewrite nutrient-management and stormwater-runoff controls as required under the Jordan Lake and Falls Lake rules. Ongoing studies by the newly formed North Carolina Policy Collaboratory at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill are also looking at a wide range of practices and their environmental effects, which could shape legislative action statewide.

Bill Holman, who was appointed during former Gov. Jim Hunt’s administration to guide cleanup efforts and new water quality protections, said that given the focus caused by Matthew, North Carolina has another chance to renew its efforts.

Driving change in the 1990s, he said, was consensus among eastern legislators, particularly those from districts around Pamlico Sound, that something had to be done upstream.

“There was a lot momentum on comprehensive reduction of pollution from agriculture and municipalities. It was a combination of the fish kills along the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico, and then the floods, that drove a lot policy and a lot of investment,” said Holman, now the state director with the Conservation Fund and recently an adviser to Gov. Roy Cooper’s transition team. “Since then, we’ve stalled. We still have pollution issues and we still have flooding issues. I hope that the Matthew recovery can be a catalyst for better policy and more investment.”

More Buyouts Considered

Reaction to the American Rivers report released Tuesday was yet another reminder that there is not a lot of agreement between riverkeepers and large-scale farmers in eastern North Carolina.

Environmental groups said the report, which focuses on the effects of massive livestock operations along the two river systems, underlines the need for better regulation and enforcement.

Farm groups called it a flawed, biased effort that ignores a greater threat from local governments.

“The American Rivers advocacy report is not an honest assessment of the most impaired waters in North Carolina,” Andy Curliss, chief executive officer of the North Carolina Pork Council, said in a statement. “This year, it is part of a coordinated campaign aimed at unfairly attacking North Carolina agriculture and livestock farmers. A true assessment at impaired waters in North Carolina will show that the greatest threats come from large municipalities, not farms.”

The long-running disagreement between the two sides has played out in both the halls of the legislature and on billboards along the four-lane highways connecting Raleigh and the coast. Despite the bitter battle, there is a place where both agriculture and water quality advocates appear to agree – the problem of concentrated animal operations in the 100-year floodplain.

Last year offered proof of the effectiveness of moving large-scale hog farms out of the floodplains of eastern North Carolina.

The strategy was first put in place in 1999 after the devastation of farming regions during Hurricane Floyd and the subsequent decline in water quality. The Clean Water Management Trust Fund was tapped for $18.7 million in grants to buy out 43 farm operations and close more 106 waste ponds that were operating in the 100-year floodplain.

More recently, with Hurricane Matthew in October 2016, a storm of similar destructiveness and heavy flooding, the number of breached dams and berms and the loss of hogs were a fraction of what was seen in 1999. Earthen dams at two ponds were breached during Matthew and 14 were flooded, compared to 50 flooded during Floyd. The industry estimated a loss of 3,000 hogs from Matthew, compared to the official count of 21,474 attributed to Floyd.

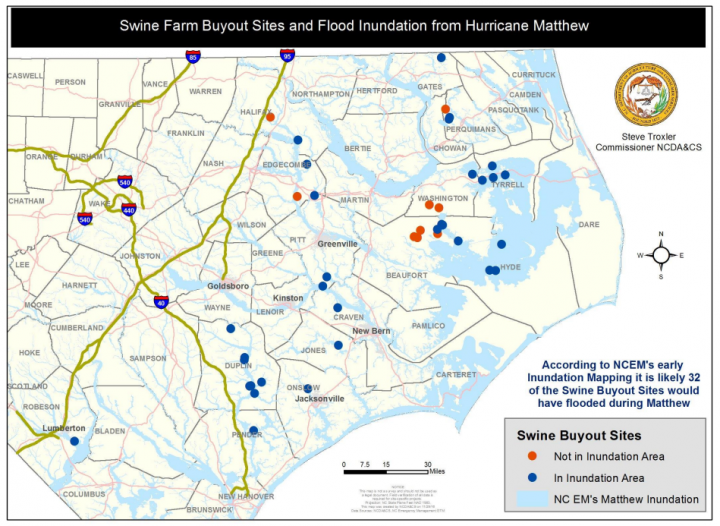

State agriculture officials estimate that 32 of the 43 swine farm buyout sites would have flooded during Hurricane Matthew.

Upper Neuse Riverkeeper Matthew Starr said the lesson from last year is that they buyout strategy worked.

Starr said the new listing of the two rivers in the report should drive home the need for action on non-point pollution sources. Restoring funds for the buyout is one of the best ways to accomplish that, he said.

“The agreement to refund this voluntary program is a win-win, which is something hard to come by in today’s political climate,” Starr said. “Removing the remaining industrial swine facilities from the 100-year floodplain makes sense for the environment, public health and for the economy of eastern North Carolina.”

Curliss responded that the Pork Council would consider the buyout proposal.

“The North Carolina Pork Council will continue to engage in productive conversations about a possible voluntary buyout program,” he said in a written response to Coastal Review. “We have supported such programs in the past.”

In a presentation to legislators late last year, Division of Soil and Water Conservation officials voiced support for the buyout program, saying it would help farmers and water quality.

Department of Environmental Quality spokesperson Jamie Kritzer said this week that DEQ is aware of continuing discussions about another round of funding for the buyout program.

“It’s our understanding there are ongoing discussions concerning a voluntary buyout and we encourage those discussions to continue,” Kritzer said in an email to Coastal Review.

The 100-Year Floodplain Swine Buyout program established under the Clean Water Management Trust Fund and administered by the state Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services’ Division Soil and Water Conservation is currently out of money, having exhausted $18.7 million in Clean Water Management Trust Fund grants since 1999.

Brian Long, spokesman with the state agriculture department, confirmed the program, while not currently funded, is still intact.

“The structures and procedures are in place for the program to continue,” Long said. “However, the Division of Soil and Water Conservation’s technical staff is currently handling many requests for assistance related to recovery from Hurricane Matthew, and that creates competition for staff resources.”

This year, the program will finalize the closure of the last three ponds on its list. While covering the costs for 43 operations in 15 counties, the list of applicants was far greater with 138 farms applying and more than $100 million requested.

In addition to decommissioning the waste lagoons and hog houses in the floodplain, the fund also purchases development rights, provides technical assistance and pays for conservation improvements, such surveying costs and other acquisition expenses. In addition to taking the area out of operation as a feedlot, it also prohibits use of the floodplain acreage as spray fields and requires a 50-foot forested buffer on all streams.

The conservation land can, however, be used for row crops.

Holman said that, given the amount sought during the earlier rounds of funding, there’s likely to be strong demand again.

“We ran out of funding before we ran out of farmers,” he said. “My guess is that there would be swine producers who would be interested in another round or maybe two.”

Poultry Farms Too?

Doing something similar with the poultry industry could also help water quality, but such a move would be more difficult.

Starr and others are calling for the swine buyout to be expanded to include poultry operations. Losses in the poultry industry during Matthew, an estimated 1.8 million chickens and turkeys, far outpaced other livestock.

But the fast-growing poultry industry is not under the same kind of restrictions as the hog industry. Unlike hog farms, the poultry industry’s waste output is considered “dry waste” and falls under different regulations in which operations are “deemed permitted” if they are built according to certain standards.

Currently, the state has no requirement on building poultry houses within the 100-year floodplain, as it does on swine operations. Holman said that a floodplain restriction is needed for a poultry buyout to work as effectively as the swine buyout.

“You had the confidence that an operation wasn’t just going to move to another place in the floodplain,” Holman said of requirement.