NAGS HEAD – Coastal North Carolina could be looking into a budgetary abyss if local and state entities don’t adapt quickly to new funding realities.

“With this new administration, it’s not going to be business as usual,” Kathleen Riely, executive director of North Carolina Beach, Inlet and Waterways Association, said at the nonprofit’s annual meeting held last week. “I cannot emphasize enough, if the state doesn’t have skin in the game, we will be passed over for coastal funds, I can tell you that.”

Supporter Spotlight

The two-day summit at Jennette’s Pier featured numerous presentations about coastal projects and concerns, including water resources and management, dredging and beach nourishment, floodplain mapping, homeowners insurance and the economic and environmental value of oyster reef restoration.

But to those who filled the large-windowed meeting room overlooking the beach – representatives from local governments, nonprofits and state and federal agencies – headaches over funding was the overarching theme.

“The whole scene is changing beneath our feet, not just at the federal level, but at the state level,” said James Leutze, the association’s chairman. “Believe me, it’s going to change and we need to be prepared for that change.”

Even though the 2017 federal budget continuing resolution is the most immediate unknown – the deadline is the end of April – there are also worries for future coastal budgets, said Derek Brockbank, executive director of the nonprofit American Shore and Beach Preservation Association.

According to Brockbank’s presentation, the president’s proposed budget would eliminate the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coastal Zone Management Program, Sea Grant, the Environmental Protection Agency’s Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health, or BEACH, Act programs, water quality monitoring and coastal resilience grants. The spending plan would also cut funds for the Army Corps of Engineers, other NOAA programs and the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

But funding potentially could be found under a cloak of another color: the much anticipated and yet-to-be-seen $1 trillion infrastructure bill. If the question is “What is in the infrastructure package?” Brockbank said, then the answer can be, “Whatever you want it to be.”

Supporter Spotlight

Of course, infrastructure would include roads and bridges, he said. But it could just as well include beaches, dunes and wetlands.

The American Shore association is calling for $5 billion over the next 10 years for “shore infrastructure” projects. Some proposals to fund the overall infrastructure package have included tolling, private-public partnerships and tax credits. But no one expects to see a lot of federal dollars.

“The bottom line is beach programs are not going to pay for themselves,” Brockbank said “Again, this is so wrapped up in the broader political dynamic happening right now.”

On the other hand, he added, the good thing an infrastructure bill has going for it is that it has bipartisan appeal.

Both sides of the aisle are also represented in the House’s Congressional Coastal Communities Caucus, which has about 35 members representing both parties, liberals and conservatives, he said.

Former Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-La., is also putting together a coastal consortium that will work on creating a coastal infrastructure spending bill to present at the appropriate time.

But Brockbank warned that coastal interests are up against the Washington, D.C., trend to starve the federal bureaucracy.

“Be that squeaky wheel – call your senators,” he said. “Invite them to your beach in August.”

Congress members are not the only people who appreciate the beach. Information culled from the 2016 update of the state’s Beach and Inlet Management Plan – better known as the BIMP – show that about 46 percent of the 56,000 property owners on barrier islands in North Carolina have their primary residence outside the eight coastal counties.

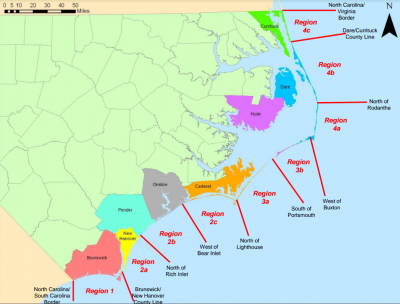

Launched in 2009, the BIMP uses physical and economic data to devise management plans for the state’s beaches and inlets. The baseline is updated every two years, or as data becomes available.

The latest BIMP update, which was approved in December 2016, calculated coastal property value in North Carolina at about $110 billion. Of that, about 17 percent is owned by non-coastal North Carolina residents and about 24 percent by residents of other states.

Direct expenditures for beach- and marine-related activities statewide in the 2016 report totaled about $2.5 billion; output, sales and business activity totaled about $6.1 billion. The update also shows that millions of dollars in revenue and job value have been lost with inadequate maintenance of beaches and inlets.

“It’s a very strong argument that investing in coastal infrastructure is a big return on investment for the state,” Riely said in a phone interview after the meeting.

The association’s position is that healthy wetlands, wide beaches, deep inlets and tall dunes reduce storm risk to roads and buildings and people on the coast. At the same time, natural beaches and waterways offer recreational, economic and environmental assets for residents and visitors.

Cost shares for state and local matching funds for shoreline projects and storm losses, according to the 2016 BIMP, are estimated at $40 million to $50 million annually. The state needs about $23.5 million a year in its fund for shallow-draft dredging projects; $17.5 million for deep-draft projects; and $20 million to $35 million for beach re-nourishment projects.

The ongoing costs justify creation of a dedicated beach preservation fund, the report said. It also recommended creating a regional cooperative among coastal counties.

The future of coastal protection projects will entail a lot more than just putting sand on the beaches, Riely said. The focus now is more on projects that impede storm damage and create resilience, such as construction of engineered dunes.

The association has taken no position on sea-level rise or climate change, she said. But overall, it supports the recommendations made in the BIMP.

With the days of generous federal cost-share dollars part of the misty past, Riely said it is imperative that North Carolina establish a dedicated beach preservation fund. That way, when federal money becomes available, the cost share is already in hand.

Both New Jersey and Florida have fat, dedicated accounts that are funded by real estate transfer fees. Delaware and Louisiana also have dedicated beach funds.

In today’s competitive climate for fewer funding crumbs, that puts North Carolina at a disadvantage.

“We need to be positioned so it’s good for our coast,” Riely said. “We need to get the state on board.”