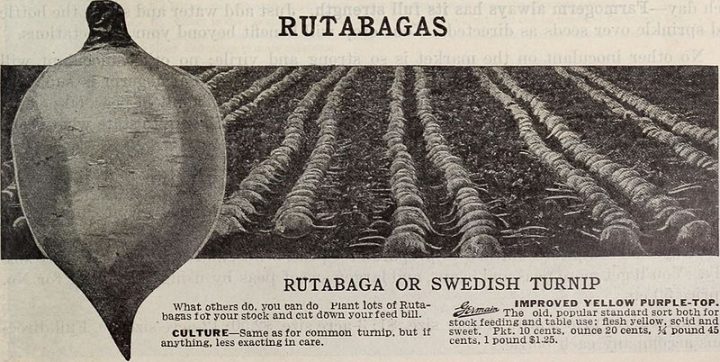

If ever there was a hard-headed Southerner, it’s the rutabaga. Forget a friendly “hey y’all.” The rock-solid root woos you with its mellow sun-gold hue and then stings you with a sharp bite. Why would anyone ever want to eat these things?

That’s what I wondered the first time I tasted rutabagas. I was a child enticed by a grandmotherly eastern North Carolina cook whose collards, I thought, were better than anything from the neighborhood 7-Eleven candy aisle. When she presented a bowl of boiled rutabaga chunks, I thrust in my fork as eagerly as a child going after birthday cake. I thought I could trust her, but the rutabaga’s dirty bitterness convinced me to never go near the vegetable again.

Supporter Spotlight

To this day, even as a food writer who must put a lot of questionable stuff in her mouth, I list rutabaga as one of the few things I don’t eat.

“Bless your heart,” my eastern North Carolina neighbors might say to me about that. Rutabagas are a beloved food tradition up and down the state’s coastal plain. Not long after the cabbage-turnip cross made the trip from its native Sweden to Canada, New England and Thomas Jefferson’s garden in the 1800s, cooks from the Outer Banks to the South Carolina line hankered for rutabagas.

The roots grew well in the region’s soils and suffered no damage buried over bitter winters or blistering summers. They provided sustenance for both humans and livestock. Rutabagas could be squirreled away in sand, a handy storage option in the days before refrigeration. Dense and filling, the knobs stretched meals. During and after World War II, Europeans depended on rutabagas to fill their bellies and still remember, and often loathe, the vegetable as famine food. Harkers Island cooks are known for extending beef stew with rutabagas and cornmeal dumplings.

Rutabagas were important to livestock farmers, too. In the mid-1800s, grower J.W. Brewster yielded 1,000 bushels of rutabagas, or 5,500 livestock feeds, on an acre of land that produced just 50 bushels of corn, about 400 feeds, the University of South Carolina reports at its American Heritage Vegetables website.

Nowadays, rutabagas are mostly a matter of nostalgia on the Carolina coast. Over the years, they have become harder to find. Supermarket shoppers are more interested in carrots and potatoes than ugly wax-coated rutabagas. At farmers’ markets, folks pick over rutabagas for flashy, fuchsia beets and velvety sweet potatoes.

Supporter Spotlight

In her cookbook “Deep Run Roots” (Little, Brown and Co., 2016), a tribute to North Carolina coastal plain cooking, eastern North Carolina’s most famous chef, Vivian Howard, dedicates an entire chapter to rutabagas. She prepares them with an assertive Kinston-area cook who sharply advises Howard on how to cut and cook the roots. In this part of North Carolina, cubed or sliced rutabagas are usually stewed with fatback and seasoned plainly with salt and pepper. Their pungent greens may be boiled with the roots, an extra special treat as far as rutabaga lovers are concerned.

My mother was one of them. An Italian, she adored the bitter flavor of chicory, arugula and broccoli rabe. While living on the North Carolina coast, rutabagas were her favorites. She may have experienced them differently than me. Some people describe rutabagas as only slightly bitter with an earthy sweetness. Our perception of bitter roots and greens depends on genes that make us either insensitive tasters or super tasters. The latter group may find rutabagas too bitter to eat.

Cooks, both amateur and professional, tend to tame the rutabaga’s bitterness. Chefs might sweeten a mash with bourbon and maple syrup. A Swansboro home cook I knew layered sliced rutabagas and potatoes in a creamy au gratin. Down in Carolina beach, I met a chef who makes rutabaga soup with apples. Howard offers a recipe for bacon-roasted rutabagas she serves with pork tenderloin.

As I review recipes, I start thinking about raw, shaved rutabagas with honey mustard dressing. I think about sautéing sausage and firm, sweet pears to scatter over rutabaga French fries and then drizzling the whole thing with some sort of sweet and spicy sauce.

But to eat rutabagas simply stewed, and oftentimes mashed, as they have been for so many years in eastern North Carolina is to honor the hardworking families who shaped our coast’s humble and now popular food culture. They had to eat what they could grow and store. My modern refrigerator is full of other choices, but I’m giving rutabagas another chance, maybe with a little honey and a lot of butter.

Stewed Rutabagas

2 3/4-inch slices of salt pork

2 medium rutabagas, peeled and either sliced or cubed

About 1 quart of water

1 teaspoon of sugar

Salt and black pepper

2-3 tablespoons of melted butter

1 tablespoon of honey

Place a heavy, medium saucepan set over medium heat. Lay the salt pork in the plan and cook until fat is rendered. Add the rutabagas and cover with water. Add sugar. Increase heat to high. Bring rutabagas to a boil, reduce heat and simmer until rutabagas are as tender as potatoes. Drain, season with salt and pepper. Drizzle with butter and honey. Makes 4 to 6 servings.