COLUMBIA – Pocosin land is supposed to be boggy. Nature designed it to be spongy and moist, creating a bulwark against wildfires and a haven for wild animals and plants. It is also a great carbon sink, one of its newly appreciated attributes.

When Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge was established in the 1991, the peat bogs had been drained and were dried out like crusty soil in a neglected potted plant. Instead of a firewall, it was fire fuel. Instead of holding carbon harmlessly in its swampy depths, it released it into the air.

Supporter Spotlight

But lately, the boggiest thing at the refuge seems to be a squabble over whether the refuge’s pocosin re-wetting project or Mother Nature is responsible for persistent flooding of surrounding farmland, with politicians in the farmers’ corner.

In recent years, the decades-long effort to restore wetlands at Pocosin Lakes has coincided with biblical rainfall. Farmlands adjacent to the refuge have been inundated, leaving crops rotting in drowned fields. Landowners blame the refuge for mismanagement of stormwater. Refuge officials say the runoff would have happened, restoration or no restoration, because of a series of deluges this year from hurricanes Julia, Hermine and Matthew.

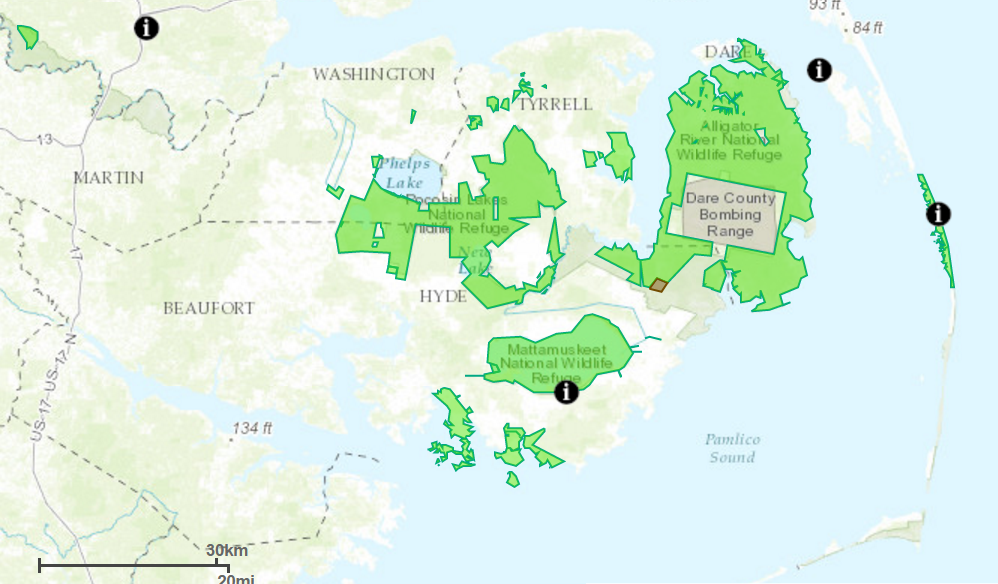

Pocosin Lakes refuge encompasses parts of Hyde, Tyrrell and Washington counties, a total of 110,000 acres of some of the wildest land in North Carolina’s coastal plain. These are also among the state’s poorest and least populated counties, with wildlife far outnumbering humans. Agriculture and timber remain important industries.

During a post-Hermine visit to Washington and Tyrrell counties in September, Gov. Pat McCrory and Agriculture Commissioner Steven Troxler publicly blamed federal regulations for the flooding.

“It appears that artificial manipulation of the water table at Pocosin Lakes NWR has again resulted in flooding of neighboring agricultural lands (which) are of great agricultural significance to North Carolina and the nation,” Troxler said later in a letter dated Oct. 4 to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Dan Ashe.

Supporter Spotlight

But refuge manager Howard Phillips said most of the runoff is related to excess rainfall that naturally drains downhill.

“Whenever anybody comes to us and they think this is causing anything, we go out and evaluate it,” he said. “Most of the time, it’s the amount of rainfall, or some other natural factor out there that we can’t control.”

For example, beavers have blocked a culvert in a canal that is shared with a private farm, Phillips said. The refuge has been working to re-direct the water.

As is often the case in clashes involving public natural resources, private property and people’s livelihoods, the situation is complicated, long-standing and potentially far-reaching. Floods and fires are health and safety hazards, and climate change is threatening to make both conditions more of a threat in an area vulnerable to both.

“We’re trying to mimic the natural hydrology as much as we can,” Phillips said. “Our mission is to restore pocosin wetlands. But one of the main reasons we’re doing this is because of the catastrophic wildfires.”

Another major benefit is the land’s value in carbon sequestration.

Pocosin, which means “swamp on a hill” – is shrubby peat wetland. Composed of organic material that decayed very slowly under the wet conditions, the peat has built up over centuries to a barely discernable dome.

As climate change has become a critical environmental issue, peat soil, composed of 50 percent carbon, has become much more interesting to scientists. Although peatland is only 3 percent of the Earth’s surface, it stores more than twice the carbon of all forests combined. Logic would have it that restored pocosin lands would hold more carbon. Conversely, if the peat burns, massive amounts of carbon are released into the environment. Dried-out peat, even when not burning, is believed to release some carbon.

“Some people have described this peat as pre-charcoal,” Phillips said.

There were two major fires in Pocosin Lakes in recent memory: the 1985 Allen Road fire , which burned 100,000 acres of land in Washington, Hyde and Tyrrell counties, and the 2008 Evans Road fire, on the tail end of a severe drought, burned for longer than six months on 50,000 acres in Alligator River and Pocosin Lakes refuges. The Evans Road fire alone cost $19 million to fight, with federal funds covering 60 percent of the expense.

Another major fire, the Pains Bay fire near Alligator River refuge in Dare County, burned 45,000 acres in May 2011. Smoke from the smoldering peat restricted training missions for weeks at the bombing range in Dare County used by Navy and Air Force jet pilots.

“We’re trying to reduce the severity and intensity of the fires that occur in these peatland areas,” Phillips said.

Three areas with the most ditching, totaling 35,000 acres, are being restored, the refuge manager said. About 20,000 acres – restoration area No. 1– is restored as much as it can be, Phillips said. In area No. 2, he said, quite a bit needs to be done. But it turns out that area No. 3 will not need to be restored because the Alligator River has gotten higher, making the area wetter.

But local farmers, whose lands have been flooded, are not buying the explanations. They say the problem is mismanagement of the drainage system at the refuge.

“They’re holding that water artificially high in the refuge,” said Guy Davenport, with 5,000-acre Newland Family Farm in Creswell, which borders the refuge.

Davenport said a group of about 150 farmers from Washington, Tyrrell, Hyde and Beaufort counties met during the summer with state and federal officials, including McCrory and Troxler, to discuss the issue. They met again last month in Nash County.

Some farmers have lost all or part of their crops in the floods, he said.

“I have lived here long before it was a refuge,” Davenport said in a recent telephone interview. “I have never seen anything the likes of the water there in my lifetime. They’re right about excessive rain. But a lot of this problem could have been avoided.”

Water was coming across the road, flowing “full bore” out of Lake Phelps, and indirectly coming off the refuge into the lake, Davenport said.

“They need to lower the water table,” he said. “They need to have that water table down in hurricane season. It’s a tremendous amount of acreage. You can’t just drain it overnight.”

Davenport said that it is “fallacy” that re-wetting pocosin provides fire protection.

“That thing has always burned,” he said. “When you get dry enough, you’re going to have fires … that’s a fact.”

Before the land was acquired for the refuge, there had been a partnership called Peat Methanol Associates that had proposed to mine peat from 15,000 acres to synthetically produce 60 million gallons of methanol fuel per year over 30 years. The developer eventually withdrew its permit application.

Much of the land in Pocosin Lakes was ditched in the 1950s and ’60s. Massive canals had been cut through the peat domes, as well as thousands of acres in surrounding swamplands in northeastern North Carolina. The channels were cut north-south and east-west, creating 320-acre blocks of land, crisscrossed by smaller channels.

Water drained into the lateral ditches, then to collector canals then to main canals then to outlet canals, then to the Pungo River.

In a partnership with the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the refuge implemented a hydrology restoration plan in the early 1990s. Water levels, which are allowed to fluctuate naturally, are determined by water control structures, rainfall and evapotranspiration. Currently, there is rewetting technology on about 18 percent of the refuge, and work on the plan will continue as funds allow.

Ditching and draining of swampland has been done since the founding of the nation. In fact, the oldest such canal – still in use in the Dismal Swamp – was ordered by none other than George Washington.

Typical swamplands are usually lower than surrounding lands, Phillips said, so water naturally drains to them. In contrast, the peatlands at Pocosin Lakes are domed, with an elevation of about 17 feet in restoration areas. The only water supply is rainfall, so once the restoration infrastructure was in place, it was a matter of waiting for rainfall to bring levels back up.

But in the last three years, rainfall has been extraordinarily high, by double digits, Phillips said. Normally, there had been about 51 inches a year, with all but 20 inches of that taken up by evaporation and plants. Last year there was about 71 inches. In 2016, the three storms dumped epic amounts of rain, leaving no recovery time in between.

In normal rain conditions, a healthy Pocosin welcomes water. “The peat would soak up the water like a sponge and release it very slowly,” Phillips said. “If it’s completely dried out, it becomes hydrophobic.”

Parched peat can burn for months and the fire can penetrate deep into the earth. What is burning up is decayed plants and animals.

“It gets really hot,” Phillips said. “It puts out tons of carbon.”

The payoff for re-wetting pocosin became evident when a wildfire in the refuge quit burning at the restored area, he said. But its value as a carbon sink, absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, has become increasingly important as a way to offset the production of greenhouse gases blamed for climate change.

Back in the late ’80s, the refuge land was donated to the Nature Conservancy, a nonprofit environmental group, which then transferred it to Fish and Wildlife. But the group has remained involved in conservation efforts in northeastern North Carolina, including the restoration of Pocosin and building of oyster reefs, said Debbie Crane, North Carolina chapter communications director.

The conservancy is currently conducting tests in two small blocks of land in the refuge to measure carbon output, Crane said. One area is restored and the other is not restored; the experiment is expected to continue for the next two to three years. If it is proven that dry peat releases significantly more carbon than wet peat, it could open the door for landowners to innovative new carbon markets in California, which compensate participants for keeping carbon emissions out of the environment.

“Once we show this,” Crane said, “private landowners could potentially sell carbon credits and make some money if they restore their property.”