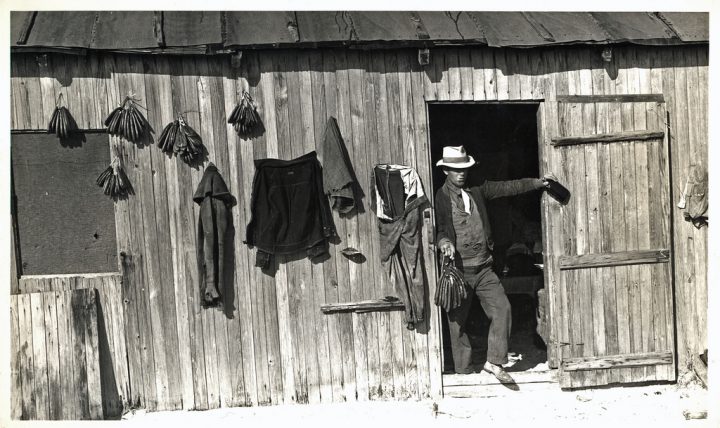

A fisherman totters against a door frame at his seaside shack. The sun is so bright in the circa 1939 black-and-white photo that the shade line of the fellow’s tilted fedora hides his eyes. Goofing for the camera, he balances a square brown liquor bottle in one hand. In the other, he holds 13 nearly foot-long, dried mullet roes strung like a necklace.

More and bigger bunches of roe hang on nails stuck into the shack’s wall. They dry in the sun alongside a jacket and pants.

Supporter Spotlight

The place is Brown’s Island, once mullet fishing central in Onslow County. Fishermen netted thousands of mullets each fall. Salted mullets packed in barrels were such a popular export from the Carolina coast that the Atlantic and North Carolina railroad between Morehead City and Goldsboro was nicknamed the Mullet Line.

Foreign cultures appreciate mullet roe way more than Americans. Italians call dried mullet row “bottarga.” The Japanese call it “karasumi.” The stuff is eaten in France, Greece, Croatia, Turkey, the Middle East, East Asia and North Africa. North Carolina commercial fishing families love mullet roe, but the spongy, bright yellow lobes etched in thread-thin red veins is a tough sale beyond the shore.

That seems to be changing.

Dried mullet roe dates back at least 3,000 years. Egyptian murals illustrate the process. Europeans and the British brought their taste for bottarga to the American Colonies.

Once upon a time, North Carolina coastal fishermen tucked dried mullet roe into their pockets. Roe gave them the protein punch they needed to get through a long day on the water. If road workers knew of someone Down East who prepared especially fine mullet roe, they might swing by to pick up a few pieces for snacks.

Supporter Spotlight

Ocracoke Island native Maude Balance shared her fond mullet roe memories when author and historian David Cecelski of Durham interviewed her for a 2004 story in the News & Observer.

“In the fall of the year, Daddy would salt mullet roe and lay them upstairs. I can see Mama’s upstairs now. We didn’t use the upstairs then, and that’s where he’d put them. They cut the roe out and wash them, salt the roe, and then, after they stay salted so long, they’d wash the salt out and just lay them out on a board and they’d dry. You’d have mullet roe just about all winter long. Now I do it, but I freeze them. I love it. And that’s something else good for breakfast, toast and mullet roe.”

As far as many chefs across America have been concerned, the only mullet roe worth their attention was imported bottarga, also made with bluefin tuna roe. In 2007, Anna Maria Fish Co. in Sarasota, Florida, started preparing bottarga using Florida mullet. By 2013, chefs’ interest grew, and the company’s bottarga was featured in the New York Times.

Back in North Carolina, famous Kinston chef Vivian Howard in 2014 highlighted local mullet on her Public Television show “A Chef’s Life.”

In season two’s episode seven, titled “The Fish Episode, Y’all,” Howard shows off huge, dried roes of North Carolina striped mullet, also known as jumping mullet, in the kitchen of her Chef & the Farmer restaurant. She demonstrates how to grate the roe for blending into butter, sprinkling on oysters and using as a “finishing salt” to give dishes “the essence of the sea.”

At PinPoint fine-dining restaurant in Wilmington, chef Dean Neff grates local mullet bottarga into aioli. He pairs that with applewood-smoked Masonboro Sound oysters served with potato chips and pickled red onions. The idea is to put an oyster, aioli and onion on a potato chip.

Neff also paired the bottarga aioli with salted triggerfish fritters. He served them alongside stewed tomatoes and orange-seasoned, braised escarole at Tales of the Fish, an annual culinary celebration staged at Wild Dunes Resort in Isle of Palms, South Carolina. Neff’s aioli was a hit among some 200 guests and acclaimed chef Mike Lata of highly rated Fig restaurant in Charleston, South Carolina. Lata called Neff the next day to ask where he could get the same bottarga.

“It kind of gives everything you put it on this kind of really fresh, ocean flavor,” Neff said. “This is actually really clean, really bright.”

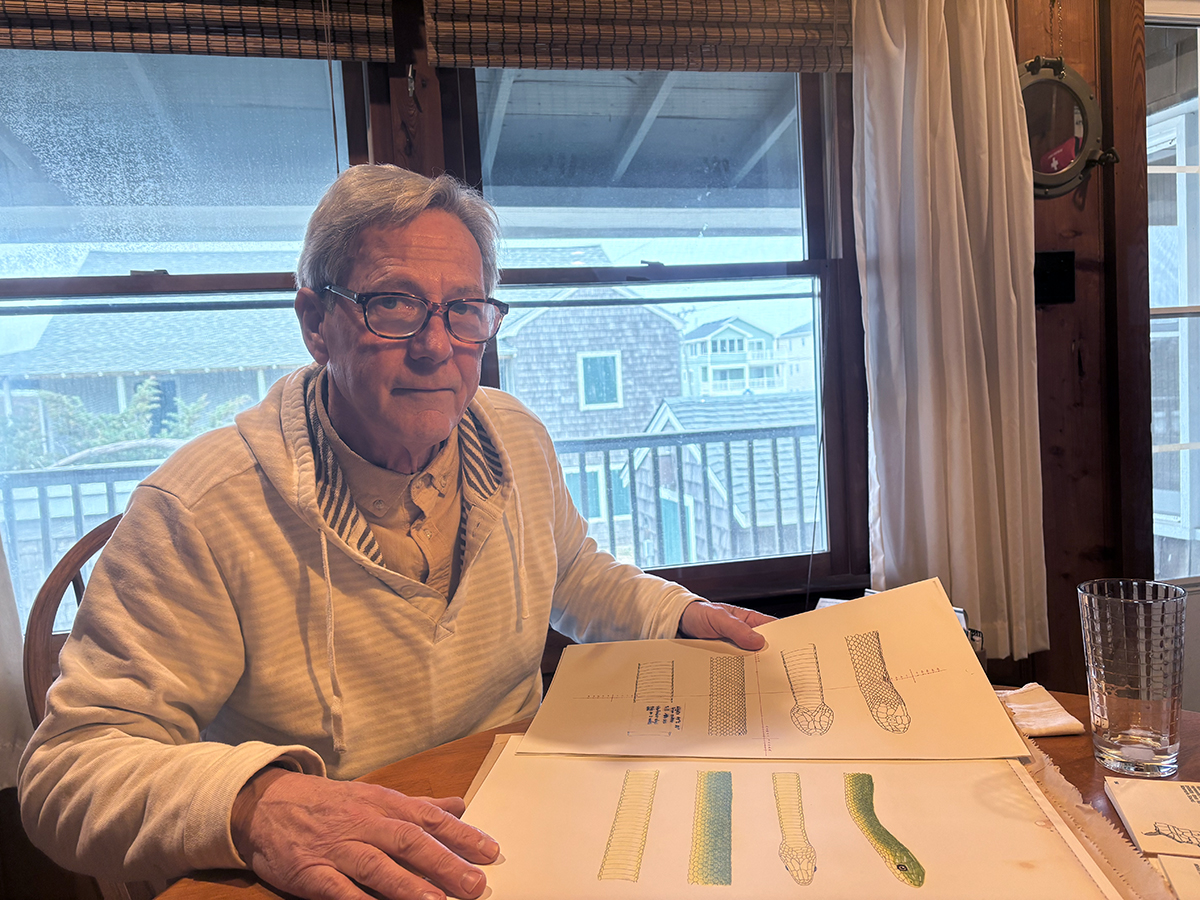

The bottarga Neff uses is prepared by two brothers with strong ties to the North Carolina coast’s celebrated fall mullet runs.

Noah and Gabriel Harrell grew up in Burgaw. As kids, they spent a lot of time at the Topsail Beach home where their mother was raised. Noah Harrell remembers being awed by shadows of giant mullet schools in the ocean. He ate mullet as a kid, but bypassed the roe.

A performer who teaches theater at Pender High School in Burgaw, Noah Harrell was working in Vermont when an Italian friend introduced him to bottarga from Italy. She tossed shaved bottarga with garlic, butter, lemon juice and pasta. “I thought it was awesome,” Harrell said.

Later, in Pender County, the Harrell brothers bought local mullet at the fish market. They discovered one fish fat with roe. They took the gift as a sign to start making their own bottarga. After all, imported bottarga costs up to $100.

The brothers carefully extract the delicate roe, coat it in olive oil and sea salt and let it air dry for about three weeks. Next, they pack the dried roe in salt and cure it for two to three months. The first year, the pair caught all the mullet they used. In 2015, they purchased a few fish to add to their haul, 30 mullets in all to produce 60 pieces of roe. They plan to keep the business small, local and seasonal.

“October and November, particularly, is mullet season here in Pender County. I like that ritual,” Noah Harrell said. “It’s always nice to see those traditions that make sense seasonally. Is it coincidence? I don’t know. But mullet run in the fall, and the fall is the perfect time to dry the roe. I feel a connection.”

“It tastes like the beach. It tastes like marsh and salt air and all the good flavors of coastal eating and living that I love.”