First of two parts

NORTHEASTERN NORTH CAROLINA — As the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service’s red wolf recovery program here marked its 25th anniversary in 2012, it was basking in nationwide accolades as a groundbreaking conservation success. Just four years later, it is teetering on the edge of failure, a turn of fate fanned by politics, mistaken identity and public ill will.

Supporter Spotlight

“There’s something going on and I can’t figure out why the agency has been so willing to backtrack,” said Ron Sutherland, a Durham-based scientist with the Wildlands Network. “The red wolf program in the Fish and Wildlife Service has basically been drawn and quartered.”

Sutherland said that there has been no response from the agency to a petition submitted in July that was signed by 500,000 people in support of wild red wolves, which are protected under the Endangered Species Act.

Critics say the program has been a failure from the outset and that the Fish and Wildlife Service had released wolves on private property without the written permission of landowners.

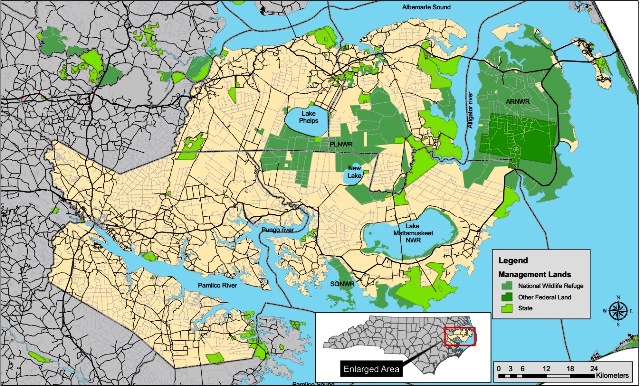

Red wolves had been declared extinct in the wild when four pairs of captive wolves were transferred from Texas to the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in 1987. Through intensive management tactics that included sneaking captive-bred pups into dens with wild-born pups, the population grew steadily. At its height in 2005-07, there were about 130 red wolves in the forested recovery area spanning 1.7 million acres of public and private land in Hyde, Dare, Tyrrell, Washington and Beaufort counties.

Today, there are just 45 wolves remaining in the wilds of northeastern North Carolina, as well as 200 or so in captivity, and Fish and Wildlife has sharply scaled back the recovery program.

Supporter Spotlight

In September, the agency announced, after a two-year review of the program, that by 2017 it planned to reduce wolf territory to an area in Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge and the military bombing range in Dare County. Wolves outside that range would be removed to captive populations that reside in numerous zoos.

“It was disheartening to see how they want to pull the animals back to almost where they started the program,” said Kim Wheeler, executive director of the Tyrrell County-based Red Wolf Coalition, a nonprofit education and advocacy group that started in 1997. “You can only have so many wolves in so much space – everybody needs their own room and their own territory.”

Red wolf recovery would require changes to “secure” the wild and captive populations, the agency said. In addition, it acknowledged that there are questions about whether the wolves’ genetics qualify for it to be classified under the Endangered Species Act.

Shortly after the agency’s announcement, U.S. District Judge Terrence Boyle issued a preliminary injunction that forbade removal of wolves from private property, unless it can be shown there is a threat to humans, pets or livestock. In issuing the order, Boyle accused the wildlife service of failing to adequately protect the wolves.

“What had been happening lately is that individual landowners have required wolves to be removed from their property, because they don’t like them,” said Jason Rylander, senior attorney for Defenders of Wildlife, one of the plaintiffs. “They can’t be removed just because they’re present on the property.”

An earlier lawsuit ruled on by the same judge led to a ban in 2014 of nighttime coyote hunting in the recovery area, a practice that conservation groups blamed for a spike in wolf gunshot deaths.

The end result of the recent injunction is that while it is under effect, the wildlife service’s plan to remove wolves in all but the Dare County and Alligator River area will not be allowed, essentially forestalling its plan.

The program’s path from bold experiment, to successful innovation, to despair for its future is perhaps more dramatic, and compressed, than most accounts of wildlife-conservation efforts.

Twenty years after the first red wolves were released onto Alligator River lands, more than 100 wolves were inhabitants, and the program was credited as a model for other successful efforts.

“That was the prototype wolf-recovery program that gave legs to the wolf-recovery programs in Yellowstone and the northern Rockies, as well as for the Mexican wolf, Walter Medvid, executive director of the Minneapolis-based International Wolf Center, said in a 2007 article in The Virginian-Pilot.

Medvid said that top predators such as wolves are good for ecological stability and help keep prey populations healthy and vigorous.

Smaller than gray wolves but bigger than coyotes, red wolves weigh about 55 to 85 pounds and are brown with patches of red behind their ears. Long ago, they ranged from southern New England to Florida and as far west as central Missouri and Texas before being gradually hunted to near-extinction. By the 1970s, fewer than 100 red wolves were believed to exist on the Gulf Coast.

An analysis of species characteristics was done by the wildlife service before 14 wolves were selected to begin a captive-breeding program. Four pairs of those wolves were chosen for release in 1987 in Alligator River, an area with natural boundaries and plenty of prey.

Sparsely developed, heavily wooded northeastern North Carolina seemed as if it would be perfect habitat for red wolves, a shy creature not known for aggression toward humans. But the red wolf preys on deer and roams private as well as public land. Conservationists may regard the wolf as an important part of the ecosystem, but to a significant number of landowners and hunters, the wolf is little more than an interloper and a competitor. And to the wolf’s misfortune, it looks very similar to a coyote, which arrived in the region not long after the wolf’s re-introduction. Shooting wolves is illegal; hunting coyotes is permitted.

Wolves will mate with coyotes if their mate is killed, exacerbating a threat to the species: hybridization. But the wildlife service’s recovery team developed an effective tactic that used a sterilized coyote to serve as a “placeholder” in keeping other coyotes out of its territory. Before it was discontinued, the measure was proving to curtail the problem with diluting the red wolf genes with those of coyotes. The controversial issue of whether the red wolf is a separate species is still being debated by the wildlife service.

Another successful method the recovery team devised is putting similarly aged captive-bred pups in with other pups in a wild den, after sprinkling them with a little urine from the wild pups. To the team’s joy, the mothers accepted the pups as their own, helping to ensure the genetic viability of the species.

But from the beginning, gunshot mortalities had been a growing issue with red wolf management. By 2003, 28 wolves had been shot. Between 2004 and 2011, another 52 wolves had been shot, despite possible penalties of up to a year in prison and a fine of $100,000. When coyote hunting was expanded in 2012 to nighttime hours, shooting deaths of wolves increased again.

But when the judge later restricted coyote hunting, the political winds seem to turn in a fury toward the wolves. Pages filled with nasty comments about the wolves started cropping up on internet hunting forums. Legislators started hearing demands from constituents to do something about the wolves.

In January 2015, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission adopted a resolution asking the wildlife service to end the red wolf project, and another resolution asking the wildlife service to remove all “unauthorized releases” of wolves and their offspring from private land.

U.S. Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., is among those who have called for eliminating the red wolf recovery program.

Tillis, speaking in September at a House Committee on Natural Resources hearing on the program, said the program had failed to meet population recovery goals for the red wolf while negatively affecting North Carolina landowners and the populations of several other native species. He said 514 private landowners and farmers had sent individual requests to the Fish and Wildlife Service to not allow red wolves on their land.

“Before we do anything more in North Carolina, I think it makes the most sense to shut the program down to figure out how to do it right and build some credibility with the landowners,” Tillis said during the hearing. “There is a less than respectful history of dialogue between folks in North Carolina and the Fish and Wildlife Service. This is going to be an issue my office will be focused on for as long as I’m a U.S. senator.”

Wheeler, of the Red Wolf Coalition, said the issue was more political than she ever thought it would be. “Certainly, our red wolves are getting caught in that political mess,” she said.

To Learn More

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Red Wolf Recovery Program

- North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission’s red wolf resolution

Thursday: Understanding the opposition