People in North Carolina have always had the right to enjoy the state’s oceanfront beaches, though some of that beach might be owned by private land owners. They are granted that right by the so-called “public trust doctrine,” an ancient legal principle with roots in antiquity.

The doctrine has been legally challenged unsuccessfully in North Carolina before. But a case, Nies vs. Emerald Isle, now before the state Supreme Court raises new fears that the public’s right to use our beaches might be restricted.

Supporter Spotlight

Here, we explore the public trust doctrine and its history in North Carolina. We also take a look at the lawsuit and its possible ramifications.

What is the public trust doctrine? It’s a legal principle that holds that certain natural and cultural resources are preserved for public use, and that the government owns and must protect and maintain these resources for the public’s use.

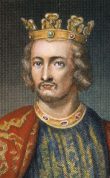

Where did it originate? The public trust doctrine has a history that can be traced to Roman law, although the modern version is more recent. The Magna Carta signed in 1215 by King John of England and rebel barons restricted the right of the king and the nobility to use estuaries and navigable waterways for private use. Over time, British law came to interpret that as meaning the public has the right to the use of certain lands and waters for the benefit of all. That legal view was transported to the British colonies and has subsequently become the basis for public trust laws and doctrine in the United States.

How is the public trust doctrine defined in North Carolina law? In some areas, public trust lands or waters are very clearly defined by the legislature and the courts. By the late 19th century the state Supreme Court held that navigable waterways and fishing rights were protected under public trust doctrine. That view has subsequently been codified in state statute, which gives the public the “right to navigate, swim, hunt, fish, and enjoy all recreational activities in the watercourses of the State …”

That same law goes on to say that the public has “… the right to freely use and enjoy the State’s ocean and estuarine beaches and public access to the beaches.”

Supporter Spotlight

Courts have defined the public beach to extend from the water’s edge to the mean high water mark, a line that fluctuates with tide amplitude and erosion. The state does not, however, own the “dry sand beach,” generally defined as the area between the mean high water mark and the base of the first line of sand dunes.

How is property defined in areas of public trust? Beachfront property owners typically own the dry sand area of the beach. It is important to note, however, that state courts have consistently held that title to the dry sand areas does not give the property owner an absolute right to privacy or to restrict access to that portion of their property.

The dry sand concept of property ownership is ingrained in North Carolina law, as well as the public’s right to access.

What about this lawsuit in Emerald Isle? Emerald Isle passed an ordinance in 2010 prohibiting “beach equipment” from being placed within 20 feet of the base of the frontal dune. The purpose was to allow emergency vehicles and other essential services an unimpeded route along the beach.

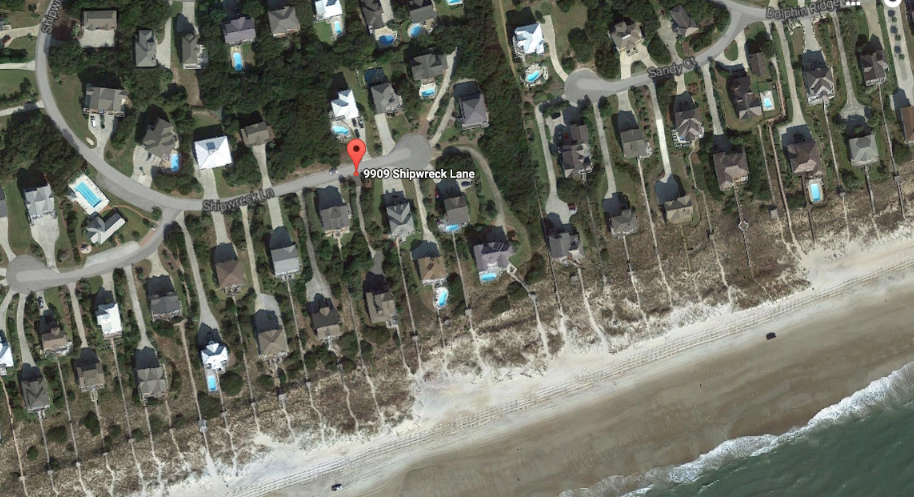

Gregory and Diane Nies, a New Jersey couple who bought their beachfront home at 9909 Shipwreck Lane in 2001, filed suit in Superior Court in 2011 claiming that the ordinance was an illegal taking of their property without just compensation. They are represented free of charge by the Pacific Legal Foundation, a California group that has been a staunch supporter of private property rights.

State Superior Court denied the claim in 2014 and granted a summary judgment for Emerald Isle. The Nieses also lost their appeal in November 2015. The state Court of Appeals, in unanimously affirming the judgment of the lower court, delivered a robust defense of the public trust doctrine.

“[W]e take notice that public right of access to dry sand beaches in North Carolina is so firmly rooted in the custom and history of North Carolina that it has become a part of the public consciousness,” the ruling states. “Native-born North Carolinians do not generally question whether the public has the right to move freely between the wet sand and dry sand portions of our ocean beaches. Though some states, such as plaintiffs’ home state of New Jersey, recognize different rights of access to their ocean beaches, no such restrictions have traditionally been practiced in North Carolina.”

The Nieses appealed to the North Carolina Supreme Court, which earlier this year agreed to a discretionary review of the case.

What is a discretionary review? It means that the court uses its own discretion to decide which cases to take. Although there are times the state Supreme Court will take a case because of an appellate court error, typically discretionary review cases are taken to clarify some point of law or a procedural matter.

What are the arguments? According to David Breemer, council for the Pacific Legal Foundation, Emerald Isle’s actions constitute government overreach.

In responding to email questions, he outlined the arguments being presented in court.

“First and foremost, the Nies’s position is that the public trust doctrine has not taken their right to control access to their land,” he wrote. “There are ways in which the right to exclude can be denied. But the town did not utilize any such avenues … Until the town uses some proper process to acquire access rights, the right to control the land remains in the Nies.”

Breemer also argues that public trust doctrine does not give government unfettered right to the use of the land. “It (the government) can buy land or easements, it can prove a right of way in court based on facts, it can ask for an easement in return for some benefit to the owners, it can seek consent. But it cannot simply say this is public trust land so we have the right to control it and you don’t,” he wrote.

Outlining Emerald Isle’s position, Frank Rush, Emerald Isle town manager, points out that the appeals court confirmed years of court rulings. “The Court of Appeals confirmed a longstanding common law right and held that the ‘ocean beaches of North Carolina … are subject to public trust rights,’” he wrote.

Rush also notes there are three public trust issues involved — public trust lands, which are the wet sand area of the beach and public trust waters are not being contested. What is at the center of the litigation are public trust use rights.

“As recognized by the General Assembly and the Court of Appeals, custom plays a role in this determination,” Rush wrote. “The Court of Appeals took ‘notice that public right of access to dry sand beaches in North Carolina is so firmly rooted in the custom and history of North Carolina that it has become a part of the public consciousness.’”

What Are the Implications? It’s important to remember that state courts have consistently held that the dry sand beach in North Carolina is privately owned but there is a compelling public trust need for access to the beach. Although the courts have held that is the case, that has never been written into law.

If the Supreme Court rules Emerald Isle unlawfully took the Nieses’ property under public trust doctrine, the consequences would be profound. It could mean that every jurisdiction on the North Carolina coast would have to go to every beachfront property owner and come to some form of understanding — an easement, consent agreement or eminent domain payment.

There is, of course, no assurance that everyone would agree to allow the public access to their property. Local officials fear a nightmare scenario of enforcement.

The Supreme Court could affirm the lower court rulings, which would give clarity to the public trust doctrine in North Carolina. The Pacific Legal Foundation could appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.