Many coastal property owners should save money if newly proposed federal flood insurance maps are adopted, but some officials fear that the maps’ changes might lead to complacency.

“They’re just maps, and people need to realize that lines on paper don’t mean there won’t be floods,” said Donna Creef, director of the planning department in Dare County, where the proposed maps would remove thousands of properties from flood zones altogether and move many others from to lower-danger zones. “Mother Nature doesn’t necessarily do what maps and lines say she will do.”

Supporter Spotlight

Dare has the largest number of rental units and second homes on the ocean and sounds in the state. Changes in the proposed maps, Creef said, would positively affect the insurance rates and or required elevations and flood-proofing of close to 16,000 buildings.

“Obviously, that’s a very good thing for a lot of people, homeowners and business owners,” she said.

The proposed maps move the 100-year flood zone along the oceanfront significantly landward, Creef said. That will result in lower flood-insurance premiums or remove any requirement for that type of protection. “But we are a little concerned that some people who get moved out of a flood zone altogether might think they no longer need flood insurance,” Creef said. “That might be the case, but there’s always a margin for error with maps, and again, storms don’t always do what the maps indicate they will do.”

The proposed maps also lower the base flood elevation, in some areas by almost half. That could allow property owners to enclose and convert to living space areas underneath houses that are on stilts.

The concern, Creef said, is that people might do those kinds of things, or simply not renew flood insurance policies when they expire, then be surprised.

Supporter Spotlight

The Federal Emergency Management Agency requires that each state produce the maps about every 10 years. According to Creef and others, one reason for the changes appears to be that the state was more involved in the mapping process this time, and state officials might well have more intimate knowledge of areas that have been flood-prone.

In other areas, such as Emerald Isle in Carteret County, the changes might have something to do with beach nourishment efforts and dune stabilization projects, but also the fact that there simply haven’t been many hurricanes in recent years.

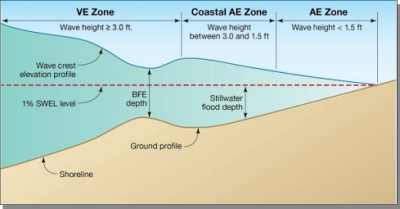

In Emerald Isle, the number of buildings in the VE zone – the highest danger zone for flooding – will decrease from 1,135 to 441 if the new maps are approved as drawn.

“For the vast majority of properties, there would be no change,” town manager Frank Rush said, but in some cases, properties have been completely removed from a VE zone and are no longer in a flood zone, while in other cases the property has been changed from a VE zone to an AE zone, which is generally less restrictive than VE.

An analysis by Josh Edmondson, the town’s planning director, shows that 99 would be added to a flood zone as a result of the new maps. As a result, the town doesn’t plan to appeal, but would help those individual property owners who choose to do so.

In high-risk areas, flood insurance is mandatory, though rating options may be available to create savings. In moderate to low-risk areas, flood insurance is recommended, but optional.

The story is different, however, in scattered pockets in Carteret County, where there are new V zones in the eastern end of the county in Smyrna, Marshallberg, North River and Straits, and more properties in flood zones in parts of Morehead City and Beaufort.

Farther south in the much more urbanized New Hanover County, planning director Ken Vafier did an analysis and concluded that the proposed maps will include more property in less flood-prone zones.

The VE zones along the Intracoastal Waterway are narrower than they are in the current maps, with more las in the less restrictive A zone, Vafier explained. Base flood elevations are also slightly reduced, he said.

“Again, this is a general trend and there are certainly some sites being proposed to change to a more restrictive zone,” Vafier explained. “Whether changes are detrimental or beneficial to a property owner will depend on each specific site, as well as the property owner’s perspective.”

Steve Stone, deputy county manager for Brunswick County, said that in general, the new maps are favorable for those concerned about flood insurance and flood insurance rates. Stone said some property in the county appear to have been removed from flood zones entirely, but the larger shift is from zones that indicate serious risks to those that predict less damage.

There are a few properties, he said, particularly along inland streams, that are placed in higher-level flood zones but “the overall, net result, I’d say, is positive for Brunswick County property owners.”

While some of the municipalities have engaged in some beach nourishment activities since the last maps came out, he doubts that impacted the maps, Most likely, it’s just more accurate mapping.

Up to the north, between roughly midway between Carteret and Dare, Beaufort County doesn’t have an oceanfront, but has a long shoreline along the Pamlico River. County planning director Seth Laughlin sounded a lot like Creef in Dare County.

“What we saw was very much unexpected,” he said of the new maps.

The unincorporated parts of the county, he said, saw improvements for 4,000 to 5,000 properties, and relatively few that would see negative changes.

Like Creef, he said he’s grateful that many property owners will likely see insurance rate cuts and might be able to do different things with their property, but he wonders about the complacency the maps might induce.

People might not renew their flood-insurance policies, he said, and could be surprised when storms don’t conform to the lines drawn on the maps. “We’re happy for people who would benefit, because flood insurance is expensive, and that cost can be a real deterrent to people who want to develop properties than contribute to the tax base, too,” Laughlin said. “But I’d be hesitant to tell people not to buy flood insurance.”

At least one coastal North Carolina county official involved in flooding issues, said some in the field were so surprised they wonder about the motives. “Is it an attempt to get the federal government off the hook for damage?” said the official, who didn’t want to be named. “The thought is, if people don’t have to buy policies, and don’t, then they have damage, the federal program doesn’t have to pay.”

But Rudi Rudolph, who as shore protection manager for Carteret County is responsible for monitoring flood insurance changes, said he believes the changes, particularly along the oceanfront are logical and based on good data, especially because the state got involved and has more and better information about specific areas along North Carolina’s coast.

He said there is some danger, however, because some hurricanes that aren’t expected to be massive 100-year storms when they hit can still surprise people, either because of direction or duration, and cause flooding one might not expect from the maps.

But Rudolph doesn’t expect widespread abandonment of flood insurance policies in areas where the new maps might indicate that possibility. Mortgage companies, he said, are not likely to let too many folks put their loans at risk.

“It’s their money that is at risk, too,” he said. “Even if you’re not in a flood zone according to the map, they can require you to have flood insurance.”

To Learn More

- N.C. Flood Mapping Program

- FEMA flood data for North Carolina

- National Flood Insurance Reform Act of 1994

- Flood insurance basics

- Flood insurance fact for coastal landowners

- Note: For the proposed flood maps check the website of the county you’re interested in.