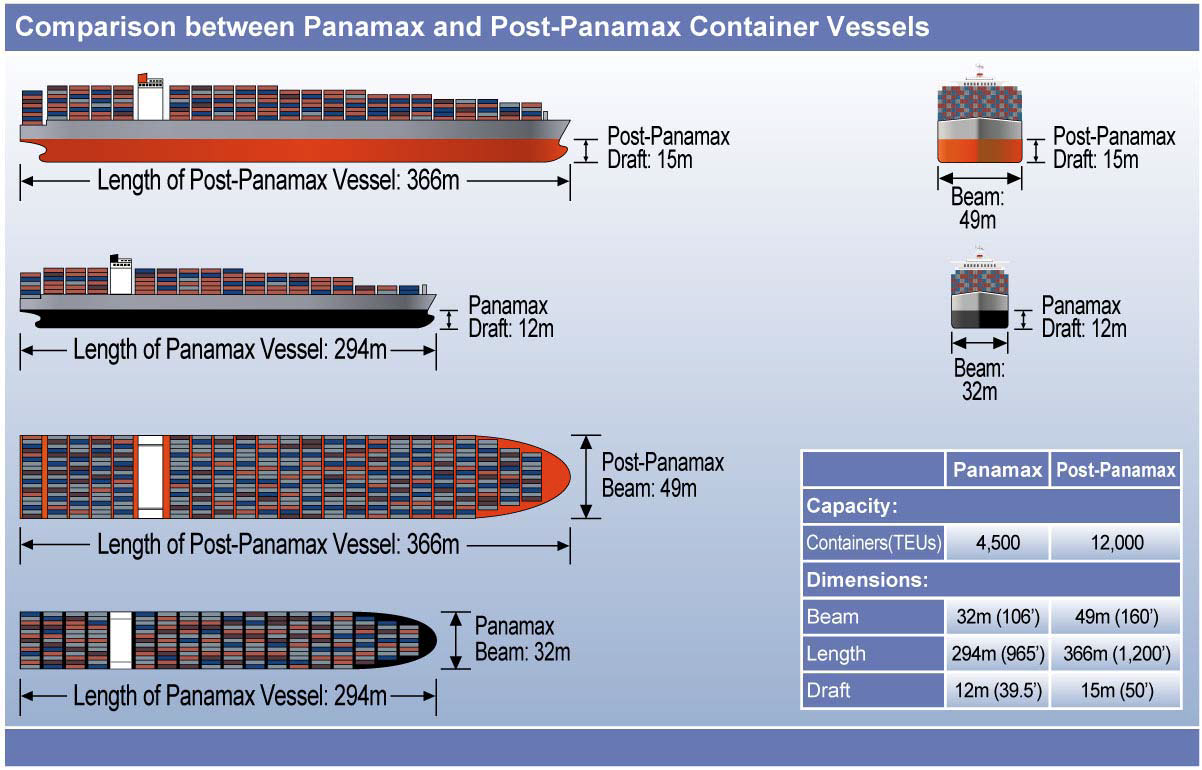

WILMINGTON — With the first of a new, larger class of ships to transit the recently widened and deepened Panama Canal calling at East Coast ports in June, state port officials here have begun investing in projects to accommodate the behemoth vessels. Meanwhile, a team of academics here is proposing what they say could be a more economical and environmentally friendly way to handle the cargo from the so-called post-Panamax ships, which are predicted to carry as much as 62 percent of the world’s container tonnage by 2030.

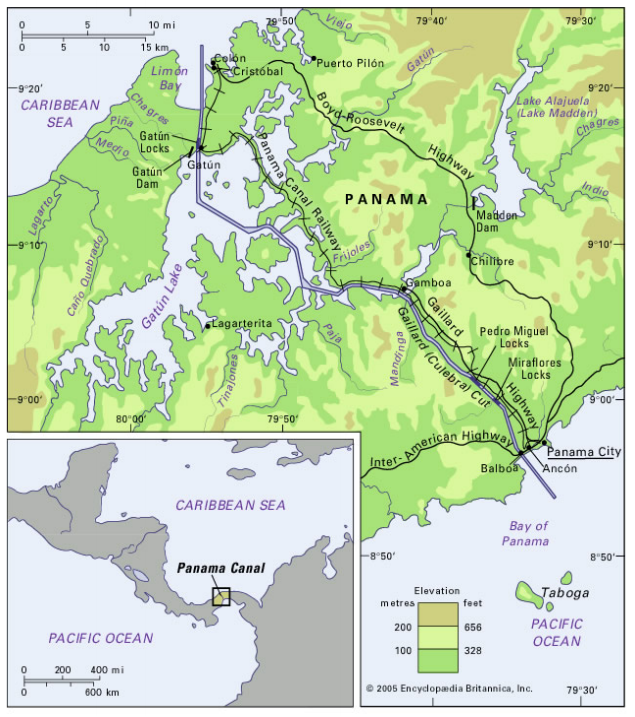

The opening of the Panama Canal to the much larger vessels was the culmination of a nine-year, $5.25 billion project expected to usher in a new era of commercial shipping. Some ports, such as Norfolk and New York, have already begun to deepen channels to the 50-foot depths and 160-foot widths these larger ships require.

Supporter Spotlight

The N.C. Ports Authority is investing more than $100 million in a port-modernization plan, said Cliff Pyron, the authority’s communications manager. The plan includes berth enhancement, purchasing new post-Panamax container cranes and installing a submerged toe wall along the berths in preparation. A $16 million dredging project to enlarge the ship’s turning basin in the Cape Fear River was approved in December 2015.

The authority had purchased for $30 million land in 2006 near Southport as a possible international port site to accommodate deeper draft ships, but the plan was put on hold in 2010 in the face of public and political opposition.

Now, a group from the University of North Carolina Wilmington is proposing that port officials consider another idea, the use of lightering barges, or lighters, flat-bottomed vessels equipped with container-handling cranes. The barges have a shallower draft and are used to load containers off-shore and bring cargo to and from ships and ports, according to a paper from Dr. Larry Cahoon and two of his graduate students in the Master of Coastal and Ocean Policy program. The barges, also known as lighters, could solve the navigational and other challenges for post-Panamax ships here, they said.

“The use of lighter barges has a lot of merit,” said Cahoon, who is an oceanographer with a background in coastal policy.

Pyron said ports authority staff were not familiar with the research.

Supporter Spotlight

Cahoon said he first learned of lighters by reading a marine technology publication. The barges were used in Hong Kong while that port expanded. They have also been used at the mouth of the Mississippi River. Cahoon’s graduate students, Jonathan Bingham and Kathryn Cyr, were eager to look into the feasibility of lighters in a local setting as part of a research project.

“Smaller ports are ambitious to catch up with some of the bigger ports in ways that aren’t ideal,” Cyr said.

As the research continued, acquiring a fleet of barges, or working with a private company to do so, began to make more sense.

“I don’t know why it’s not used more,” Bingham said.

Cahoon and his students looked at the challenges of navigating larger ships through the 26-mile long river channel and making the 90-degree turn at Battery Island to reach the port. With use of lighters, the larger ships would remain offshore and the more maneuverable barges would make the trip to and from the port. This would alleviate the considerable costs associated with making and keeping the channel navigable by post-Panamax ships.

“It isn’t a one-time cost,” he said. “It would have to be done again and again. Dredging, and re-dredging is an expensive proposition.”

By comparison, the barges are cheap, he said.

Also, with lighter barges, the river could be spared from additional environmental damage. Deepening the channel can have effects on the river system.

“One of these is saltwater intrusion,” Cahoon said. “Anyone can see the results of what has happened with this.”

Cahoon said evidence of the change is apparent in the stands of dead cypress trees upriver from the port, where salinity has increased in what was once more freshwater or brackish wetlands. “They don’t tolerate this saltier water,” he said.

Another potential benefit of lighter barges is a reduced chance of ballast water from large ships introducing invasive species into local waters. According to the paper, ballast water is responsible for the invasion of Gracilaria vermiculophylla, a seaweed, in the Cape Fear River.

“It has really caused problems for those who fish the waters,” Cahoon said. “It has made it impossible for them to work in certain areas.”

Although the use of lighter barges appears to make logistic, economic and environmental sense, according to the authors, there is a potential problem.

“The Jones Act is the biggest hurdle,” Cyr said.

The law, which is more formally known as the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, states that only ships built, registered and owned by U.S. citizens and manned domestic crews may deliver cargo by water between ports here. Cahoon said he was unaware of any U.S.-made lighters. Congress would have to issue a waiver to allow the port to use foreign-built vessels.

“It’s something they’ve done in the past, and it’s entirely possible that they’d do so in this case, too,” Cahoon said.

The team completed its research earlier this year and are eager to get the idea out to the public.

“Basically, we think it’s an idea that makes a lot of sense,” Cahoon said.