First of three parts

NAVASSA – Recently collected soil samples from the site of a former wood-treatment operation here show more of the worst contaminants from creosote are in the tidal marsh at the site than environmental officials had anticipated.

Supporter Spotlight

Federal environmental officials say they are almost ready to present to town representatives draft reports from an ongoing investigation into how to clean up and redevelop the 251-acre, former Kerr-McGee Chemical Corp. site. One conclusion from tests done so far is that there is more of “the primary contaminant of concern,” polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs, in the marsh sediment at the site than first expected, Jamie Kritzer, a spokesman for the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, said Friday.

“We’re confident we will be able to clean up the site sufficiently to protect public health and the environment in the future,” Kritzer said.

Investigative work got started a year and a half ago at the site, beginning the latest decontamination project in a predominantly black community that has for a century endured a series of environmental calamities resulting from local industries.

In this three-part special report that continues through Thursday, CRO will explore Navassa’s industrial history, how it has affected town residents and what the future may hold as the contamination is addressed and prospects for redeveloping the site become clearer.

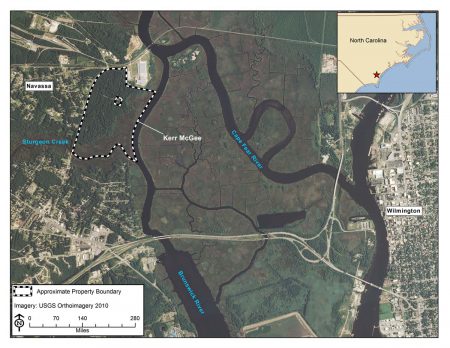

The contaminated property is a short distance across the Cape Fear and Brunswick rivers from downtown Wilmington. It was home to an operation that, under three different owners between 1936 and 1974, dried and pressure treated lumber for railroad ties, utility poles and pilings using a creosote solution as a preservative. The land, which is now fenced off and marked with “Danger – Keep Out” signs, hasn’t been occupied since 1980. That’s when the factory was dismantled. The creosote residues in unlined wastewater ponds and creosote sludge from the bottom of storage tanks were mixed with clean soil and buried on site. The coal-tar-based substance fouled groundwater, soils, the creek bottom and riverbeds. The EPA placed the site on its Superfund National Priorities List in 2010.

Supporter Spotlight

Money to clean up the site comes from the largest settlement the U.S. Justice Department has won to clean up pollution, here and at other locations. The more than $5 billion settlement against the Kerr-McGee Corp. and other related subsidiaries of Anadarko Petroleum Corp. took effect in January 2015. More than $4.4 billion goes to federal and state governments and several environmental response trusts to clean up contaminated properties. The awards are in addition to more than $270 million in recoveries from a 2011 bankruptcy settlement with Tronox Inc., the result of a fraud case in which Kerr-McGee was found to have spun off assets to a shell corporation to avoid paying billions of dollars in liabilities.

About $89.5 million of the Anadarko proceeds were designated for the investigation and cleanup of the Kerr-McGee site here, according to a May 2014 EPA document. The multistate environmental response trust received more than $4.2 million in 2011 for additional site investigations and studies in Navassa. An additional nearly $23 million, including about $900,000 received in 2011, was committed to restoring natural resources here.

The EPA is leading the investigation, which also involves the DEQ and other state and federal agencies and a court-appointed trust. Town government representatives and a local community group meet periodically to discuss the project and have been kept apprised of the work, although not everyone in Navassa is happy with the flow of information.

A public meeting, open to the entire community, to discuss the findings could happen by late summer or early fall. “I hope we can do something in August,” said Erik Spalvins, the EPA’s remedial project manager for the Superfund site.

The most recent meeting was last fall. Spalvins said more meetings are planned. The idea, he said, is stay in touch with the community.

“We have a lot of draft information and we’re trying to figure out at what point are we ready to start presenting some of the draft information. We don’t want to wait until it’s a thousand-page report. We’re trying to make sure we have a complete picture when we go to the community,” he said.

Kritzer said the fieldwork part of the investigation is “close to concluding,” but no date is certain.

The contamination is largely in the wetlands areas of the site, 30 to 40 acres. Contractors used mats to move heavy equipment out onto the marsh where they drilled into soils and sediments to take samples. Samples were also taken in upland areas at the site. Materials collected were subjected to an optical screening tool, a laser, in the field to detect PAHs.

Samples were also collected for lab assessment as a backup. Reports are being written based on the data collected but more environmental collection and sampling may be necessary. Eventually, a feasibility study will be done on the best ways to remove the creosote contamination.

‘Cre-sote’

“In the neighborhood, everybody calls it ‘cre-sote,’ without the ‘o’ in it,” Mayor Eulis Willis said recently.

In Navassa, creosote provided jobs, but Willis said the tradeoff was premature death for many here, including nearly entire families. Officials know the contamination has leached into groundwater but proving a health link, however, may not be possible.

Creosote has been widely used as a wood preservative for more than a century. It’s nasty stuff that’s also been used as a pesticide. It can make people sick, depending on the level, duration and frequency of exposure, and the EPA says it’s a probable human carcinogen. Long-term exposure, especially thorough direct contact with skin during wood treatment, has resulted in skin cancer and cancer of the scrotum.

Creosote from coal tar is the most common form of creosote in the workplace and is the type that was used at the Navassa site. Coal tar creosote is a thick, oily liquid that is typically amber to black in color. It burns easily and does not easily dissolve in water.

The EPA has classified 56 wood-treatment sites as Superfund sites since 1980. Cleanup of contaminated soil, sludge, sediments and water has been completed at about 40 of the sites.

The creosote operation in Navassa took place on about 60 acres in the western portion of the property, which officials now refer to as the production area. Much of this area is wetlands along Sturgeon Creek, a tributary of the Brunswick River. Creosote contamination was first identified in soil and water in the 1980s. State officials turned to the EPA for help when the North Carolina Department of Transportation found creosote in the marsh when it began work more than 10 years ago to replace a bridge over Sturgeon Creek on the main road into town.

“The thing that got this site into the Superfund program is that it was on the water and there was a lot of contamination found in the swamp and in the sediments,” Splavins said. “Also, the state was not getting the type of response it needed from the property owner. The states generally have a lot of control over these regulatory programs but when a state is not getting a response, they ask EPA to come in.”

The program is a safety net, Splavins explained, for contaminated sites that are too big, too complicated and too expensive for states to manage, or when the responsible party is not cooperative.

“Those are the sites Superfund is meant to catch,” Splavins said.

At one time, creosote operations could be found all around the Southeast because of the typically wet conditions here and the need for treated wood. Treating operations proliferated soon after World War II, but they started closing down in the late 1970s as environmental and workplace-safety regulations came into play.

“The way they operated, they could not do it and do it safely,” Splavins said.

Surviving Workers

Few in Navassa can remember when wood was treated with creosote here.

Louis “Bobby” Brown, 85, of Navassa, worked at the Kerr-McGee site for about three years as a young man. That’s when the operation was owned by the Gulf State Creosoting Co.

“That was one of my first jobs,” Brown said, adding that he still resides near the site. “I worked out there before I went into the army in 1951.”

Brown was Navassa’s first mayor, serving 1977-99. He’s now a member of the local committee on the Kerr-McGee site.

Brown also stays busy working for a nonprofit organization in town. Brown’s coworkers at the Countywide Community Development Corp. say he keeps a hectic schedule, but Brown calls it a “part-time” job.

Back when he held the creosote job, Brown said he worked where the bark was stripped from logs prior to being treated. That usually kept him at a distance from the boiler plant, where conditions could be much harsher.

“It was a little skin irritation if you worked around the boiler plant. Get some of that heat coming off there and you’d get some irritation,” Brown said. “About three or four of us are the only ones living that used to work out there. The rest are dead. A lot of people who used to work out there died young.”

Johnnie Willis isn’t one of them. Now 88, he can usually be found working in the garden behind his house in town. That’s where he was Friday. Rake in hand, Willis appeared undeterred by the nearly 90-degree afternoon heat. Sweltering conditions are what he remembers most about the creosote job.

“It was hard, hot work,” Willis said, adding that the Gulf States company physician doled out salt pills to workers to replace sodium in the body lost to sweat.

“I worked there all my life, off and on, and a lot of my friends did.”

Willis said he also recalled teams of a half-dozen horses pulling logs at the site, that’s how heavy the work was. A few times, Willis looked for other opportunities, including taking work at one of the local fertilizer factories. Navassa was unusual in the area in terms of employment options. Willis kept going back to the creosote plant. His father also worked a creosote job, as did his father.

“My daddy was a World War I veteran and it was enough to make a small living and get a pension,” Willis said.

Willis said the creosote never appeared to affect his health. “I had a doctor tell me I was in good shape,” he said of a recent check-up.

It was working at a fertilizer factory in town, however, that caused him health problems. “The creosote job, the heat was the worst part,” Willis said.

An Industrial Town

Fertilizer was the other major industry in Navassa’s history. The town is the namesake of the first fertilizer company to open here. Production involved reacting phosphate with sulfuric acid, which also left a toxic mess.

Mayor Willis, a Navassa native with deep family roots here, has served as an elected town official for more than 36 years. Beginning as a town councilman, his tenure includes the past 14 years as mayor. He also wrote a book on the history of the community.

“No other community in Brunswick County comes close, in terms of environmental issues,” Willis said.

Navassa and the surrounding area were home to numerous rice plantations during the Antebellum period, including one owned by Thomas Meares that produced in 1859 a record rice crop among plantations along the Cape Fear River. Slaves from West Africa, where rice was also a staple crop, were brought in to work the farms, bringing with them their native Gullah Geechee culture. Rice plantations along the river began to disappear during and after the Civil War. Former slaves and their descendants built the community here and African-Americans today comprise nearly 64 percent of the population.

One of those rice plantations was on the property now known as the Kerr-McGee site.

“The plantation house burned in 1911,” Willis said. “When the house burned, the plantation owner gave two acres in and around the plantation site to his trustees and those two families stayed there. That two acres is right in the middle of that (Kerr-McGee) tract. Everything else he sold to a lumber concern called Waccamaw Lumber.”

Waccamaw sold the property to Carolina Creosote in 1935. “That’s when they started the creosote operation,” Willis said.

EPA maps of the Kerr-McGee site show the two-acre parcel as separate, but surrounded on all sides, except for a dirt road, by Kerr-McGee property.

“The descendants of those families are still there,” Willis said, adding that one of the families had borne 19 children, 18 of which were boys, between 1935 and 1954. Only one of the 19 is still living, Willis said.

When the town incorporated in 1977, it soon qualified for a state grant to install a public water system. Navassa became the first town in the area to get public water, eliminating the need for private wells in use at the time. Willis said state environmental officials had apparently discovered by then there was a problem with the groundwater.

“The first (water) pipe that was laid was on this little dirt road that goes back to these two acres because it was realized that the water coming up under here was contaminated,” Willis said. “The woman who was living here with the 19 children, all of them were dead now, all of them died of blood-borne diseases.”

Connecting the deaths to the contamination, however, could be difficult, said Veronica Carter, a retired Army officer who serves on the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s board of directors and as the federation’s representative on the Southeastern North Carolina Environmental Justice Coalition.

“It’s going to be hard to prove,” Carter said. “There’s no medical facility in Navassa, there’s no doctor in Navassa. So there’s no health records to go back and draw that line. Yes, it makes sense to us that all these people having life expectancies in their 50s and 60s and all these various cancers and all that, that (contamination) is what caused it, but we can’t draw that causation line.”

The state Department of Health and Human Services reached a similar conclusion in 2012 when it prepared a public health assessment of the Kerr-McGee site. According to the report, it’s inconclusive whether people living near the site during the years when wood was treated could have been harmed. Although some information was gathered in 1988, 14 years after wood treatment ceased, significant environmental data was not collected until 1995. More data was collected in 2004-05.

“This data may not represent contaminant concentrations and exposure conditions during wood treating operations and the years immediately afterward,” according to the document.

As for current conditions, EPA’s report, when presented, will include the latest assessment of risks posed at the site to human health and the environment, Kritzer said.

Earlier this year, officials at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington announced its nursing students would offer health screenings for Navassa residents as part of a community partnership.

To Learn More

Wednesday: “Poster child for environmental justice”