SUNSET BEACH – The Sunset Beach Town Council voted Tuesday to file a lawsuit against the company planning to build an upscale development on a portion of land that the town says it owns.

The board made the unanimous decision one day after the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management granted a permit for a major development to Sunset Beach West LLC. The company wants to build 21 homes in a federally designated high risk area.

Supporter Spotlight

The developers received a permit from the Army Corps of Engineers on June 15 and now have all the state and federal permits needed to move ahead with the controversial project. They will still need local permits.

Town officials say the town owns a portion of nearly 25 acres of pristine oceanfront land that stretches between the last developed lots on the west end of Sunset Beach and the Bird Island Reserve. Developer Sammy Varnam contends his company owns all of the land.

Town Attorney Grady Richardson Jr. said Tuesday that he will file a lawsuit by week’s end in Brunswick County Superior Court.

“We’re going to move forward with a lawsuit seeking a judgment that upholds the town’s ownership of the land in question,” he said.

The Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit was issued Monday, five days after the Army Corps of Engineers granted Varnam federal permits to build a bridge and docking facility on the property. The Coast Guard in late May determined Varnam does not have to obtain a formal Coast Guard permit to build the bridge.

Supporter Spotlight

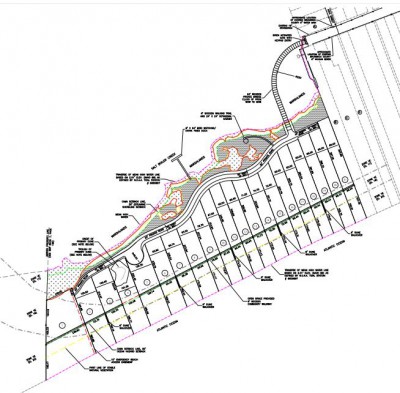

The CAMA permit and federal permits outline conditions by which the developer must abide when building a series of structures on the property, including a bulkhead, kayak and docking facility, boardwalk and gazebo, dune walkovers and a vehicular bridge that would link the subdivision to the island’s main thoroughfare.

Condition 39 of the CAMA major permit states that if a court determines any portion of the property is owned by anyone other than the applicant, the permit will be null and void “to the area the court determines is not owned by the permittee.”

“The town continues to believe we still own it,” Mayor Ron Watts said.

Varnam disagrees. “I guess the ball’s in their court now,” he said. “If they want to waste taxpayers’ money and pursue a lawsuit that they can’t win then that’s their choice. If they decide to go down that road then we are prepared. Our hope all along has been to work together with the town. We hope in the future the council feels the same towards our company. We own the property and we have legal rights that we will defend.”

Officials with the state Division of Coastal Management, which issued the CAMA permit, have maintained that the agency is not responsible for determining land ownership.

Doug Huggett, the agency’s major permit manager, did not respond to a call seeking comment, but Michele Walker, a spokeswoman for the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, stated in an email that, “it’s not the Division of Coastal Management’s job to determine property ownership.”

Proof of ownership was provided by way of a deed to the property, she wrote. “Any dispute about the validity of that deed is not up to us to decide, but must be decided by a court of law,” Walker said. “Beyond that, since we are anticipating appeals to this permit, I don’t think I want to comment further.”

According to state statute, a CAMA major permit application must include a copy of the deed “or other instrument” claiming title to the property.

In April 2014 Varnam submitted a general warranty deed, a document that was prepared without an opinion of title, according to Geoff Gisler, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center.

“I think it’s somewhat shocking that the state would issue a permit when the only documents before them do not meet the statutory requirements,” Gisler said. “You would think that the permitting agencies would satisfy that basic requirement that that entity actually own the property. The state can’t shirk their responsibilities. It is a remarkable decision and we’ll be seeking records and trying to understand what led the state to reach that decision.”

Mike Giles, a coastal advocate with the North Carolina Coastal Federation, said the state permit abdicates DCM’s responsibility.

“It states in the CAMA regulations that the applicant has to have legal right to the property,” Giles said. “How can you issue a permit to develop a piece of property when the ownership is in question? If there’s a question they shouldn’t be issuing the permit. They’re passing it off to someone else. That someone else is most likely citizens that are going to have to challenge this permit.”

An appeal must be filed within 20 days from the time a permit is issued. “I feel pretty safe to say that an appeal will be filed,” Giles said.

Town officials and the law center initially raised the question last fall of whether the limited liability company owns all of the property.

The debate goes back to 1987, when Edward Mannon “Ed” Gore Sr., a well-known Sunset Beach developer and businessman, deeded a portion of the land to the town on condition the town use it to build a public parking lot within three years. The parking lot was never built.

In 2004, four years after Gore’s death, the town council passed a resolution declaring that a parking lot would be too expensive because the town would have to either buy the last developed, oceanfront lot at the west end of West Main Street or build a bridge to access the land on which a parking lot could be paved. The town board decided then to turn the deed back over to the Gore family.

The town, however, never prepared the deed and the family did not request it. Meanwhile, the Gores continued to pay taxes on the land.

The town council earlier this year rescinded the 2004 vote.

The portion of land in question is where Varnam needs to build a bridge across Bull Creek to connect the development to the main road on the island.

Asked whether he will begin construction on the bridge and other amenities on the property, he said, “We are taking it day by day. Our plans are to move forward one step at a time.”

Richardson said he will file an injunction, if necessary, to stop building.

“If it’s necessary to seek an injunction to protect the town’s interest in this land from being disturbed I’m prepared to do so,” he said. “My mission is to maintain the status quo of the parties, which means no disturbing of the land until there is determination of the titleship of this property. There’s been no permits issued by the town of Sunset Beach approving this development. That’s key.”

In addition to the CAMA major and federal permits, Varnam will have to obtain permits from the town and county. Varnam said he has not yet applied for those permits.

If a judge rules in the town’s favor, the state and federal permits would be invalid, Richardson said.

Generally speaking, he said, a lawsuit in superior court can take up to a year before a judgment is rendered. If the losing party files an appeal in the North Carolina Court of Appeals, that could take another 12 to 15 months.

Varnam has enlisted the support of Sen. Bill Rabon, R-Brunswick, who, on May 11, filed Senate Bill 875. The bill calls for the removal of three separate parcels from Sunset Beach’s town limits, including Sunset Beach West.

The de-annexation bill is on hold in the House’s Rules, Calendar and Operations committee.

Watts said he hopes that’s where it stays. Earlier this month the town hired a lobbyist to fight the proposed bill.

The proposed Sunset Beach West development has been contentious from the start. It would be built on land that was once Mad Inlet, a shallow channel that opened and closed over the centuries, separating the west end of Sunset Beach from what is now the Bird Island Reserve. It dried up in the mid-1990s.

In February 2014 the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission removed it from the inlet hazard area designation.

Varnam has said he will provide private utilities to the development, a decision that came after Brunswick County commissioners reversed an offer to allow him to tap into the county’s public utilities for water and sewer service. County commissioners backed away from their offer after the county received a letter from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service warning that if utilities were provided to the land, which is in a federally designated Coastal Barrier Resources Act or CBRA (pronounced “cobra”) zone, the county could be cut off from future federal funding.

Building is allowed in CBRA zones, but, in an effort to discourage development in these areas, the government restricts federal subsidies, including flood insurance and Federal Emergency Management Agency aid.

To Learn More