The ecology of the N.C. coast is teeming with a variety of life, but this area is also part of a larger region now recognized by an international environmental group as one of the most biologically diverse places on Earth.

The Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund in February recognized the North American Coastal Plain, a more than 800,000-square-mile area that stretches from Florida to Maine, as the world’s 36th biodiversity hotspot. The organization, based in Arlington, Va., is a joint initiative with French, European Union, Japanese and other interests around the world focused on biodiversity conservation of the most biologically rich and threatened areas by non-governmental, private-sector and community groups.

Supporter Spotlight

Now, the North American Coastal Plain joins areas such as the Cape Floristic Region in South Africa, the Mediterranean Basin and the Tropical Andes as biodiversity hotspots.

“I think there has been an awareness of this, even for decades,” said Reed Noss, with the University of Central Florida’s biology department. However, it hadn’t – until recently – received official designation as a biodiversity hotspot.

“There are a couple of factors they look at for this,” said Alan Weakley, director of the UNC Herbarium, and one of the coauthors with Noss on a study that helped establish this label. Much has to do with the number of species and endemic species found in a particular area.

“Another factor is the endangerment of the land,” he said. “How much is no longer available for these species?”

The coastal plain is high in plant diversity especially, he said, and meets the necessary threshold of more than 1,500 endemic vascular plants, those with tissues that conduct water, sap and nutrients, such as flowering plants and ferns.

Supporter Spotlight

The hotspot designation is also meant to bring attention to those areas with more than 70 percent habitat loss.

“We’ve lost 86 percent of the habitat, way above that,” Weakley said.

The research continues, but the richness of endemic plants – with 1,800 species found in the coastal plain – as well as the 138 species of native fish and 113 species of endemic reptiles, means that the region easily qualifies. Casual environmentalists might know some of the names on these lists, the Venus Flytrap or one of the area’s other insectivorous plants, for example. But there is much more here.

“This area is a real center for biodiversity and definitely meets the global criteria,” said Noss, who with a group of other scientists started a project in 2001 to map plants and animals only found in 25 or fewer counties. “We were looking at those species with a narrow range. We found that there are hotspots across the South, and most were in the coastal plain.”

A Closer Look

Noss found a number of myths and misconceptions about the coastal plain. Much of this area is flat and low in elevation, leading many to assume it lacked the geographic diversity that would encourage corresponding diversity in plants and animals. Also, there was confusion about the pattern of fire that is necessary to bring about different stages of forest in the southeastern U.S. Scientists now understand how important fire is to local ecosystems, and the area’s historical inclination of lightning-induced fires fostered the high number of endemic plant varieties.

Noss noted that the list of endemic plants keeps growing, thanks to new discoveries and changes in how plants are named and classified. Scientists are continuing to look at native species of ants, grasshoppers and lichens, which could strengthen the hotspot status for the region.

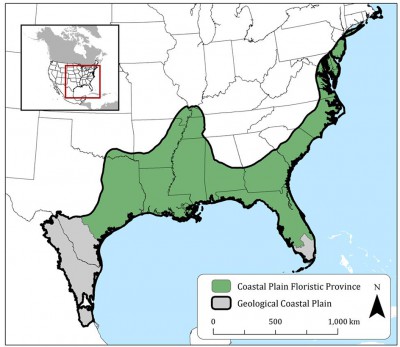

This hotspot has two subsections, the Geological Coastal Plain in Florida and Texas, and the Coastal Plain Floristic Province, which includes the area that sweeps through North Carolina’s eastern region. Noss, Weakley and the other scientists on the team delineated the borders of these areas.

“In North Carolina, the division is actually pretty sharp between the coastal plain and the Piedmont area,” Weakley said. “The areas are biologically distinct.”

The two areas, in total, are larger than most previously identified hotspots, but smaller than the Horn of Africa region. This region is about the same size as Mesoamerica, which includes Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and parts of Mexico and Panama.

The region’s vulnerability is another factor. More people live in the coastal plain and alter the native vegetation, which places local biodiversity at risk. Conservation priorities for this area are aimed at what sets it apart, such as reduction of urban sprawl and identifying potential refuges within the hotspot.

Conservation in Mind

The concept of biodiversity hotspots started to take shape in the 1980s with the work of British environmentalist Norman Meyers, American primatologist and herpetologist Russell Mittermeier and others who began to ask difficult questions about the priorities of preserving the world’s natural heritage. With so many places and species under threat, they wondered at how conservationists could help the largest number of species in the most sustainable, economical way. They determined that focusing on places with a higher percentage of diversity might be the best way.

“At that time, there were 25 regions that were recognized as irreplaceable and highly vulnerable,” Noss said.

The Florida scrub-jay is one of the few endemic bird species of the coastal plain. Photo: Reed Noss

In 2011, the number had grown to 35 areas that covered a little more than two percent of the Earth’s surface, but were thought to contain as much as 43 percent of the world’s endemic plant and animal species.

“There was some backlash,” Noss said. “Some pointed out that places with low diversity, such as the tundra boreal forests, are also valuable and vulnerable. Of course, this idea was to focus on one way to minimize the role of extinction.”

Today, the Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund, which includes Conservation International, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank, is instrumental in providing grants to protect these hotspots.

Noss and Weakley hope the biodiversity designation will mean that the Southeastern U.S. will be in a better position to receive grant funding.

“Our hope is that with the hotspot, there will be more conservation for the coastal plain, that more donors will mean more money for things like land acquisition,” Noss said.

Weakley said the designation bodes well for expanded conservation in North Carolina. “With this official standing, it provides scientists with something to point to when seeking grant money,” he said.

Hot in North Carolina

In this state, the North American Coastal Plain includes areas like the Green Swamp in Brunswick and Columbus counties, which has some of the highest fine-scale plant species richness in the world. Some plots have more than 50 species, he said. And there are the 20 to 25 insectivorous plants there.”

Also in Columbus County, Lake Waccamaw is home to the Waccamaw silverside fish, found nowhere else.

“Longleaf pine forest is also of particular concern here,” Weakley said.

Because of factors as varied as fire suppression and residential development, these forests now cover less than five percent of their former range, which leaves less habitat for species like the red-cockaded woodpecker.

“I think it is underappreciated how many people come to the area for ecotourism,” Weakley said. “More people than you might expect come to the state see the flytraps, and the orchids in the Green Swamp.”

Weakley said that preserving the coastal plain is a way to preserve this aspect of the economy and a way to protect North Carolina’s culture and history.

“You know, we are the Tar Heel State. A lot of the colonial and post-colonial past of this area is based on the products of the longleaf pine,” he said. “Those forests weren’t managed sustainably, but preserving them now also means maintaining that cultural heritage, too.”