Reprinted from N.C. Health News

RALEIGH — In a hushed conference room in the heart of Research Triangle Park, a veterinary scientist urged college students to picture what might go wrong when the wild and the tame collide.

Supporter Spotlight

To focus their thinking, Suzanne Kennedy-Stoskopf , a N.C. State University professor, shared a sobering scenario that could occur in North Carolina. It went like this:

Hungry wild pigs burst through a fence confining livestock on a small farm, as they do frequently on the coast, in the mountains and in between. Once through, the intruders push domestic pigs aside to gorge on pasture grass or feed – anything edible they find, including young animals.

Seeing the damage the next day, a farmer recognizes that feral swine breached his land. That isn’t a giant surprise because populations of the animals have exploded in the Southeast.

But he never considers what the intruders might have carried in.

That remains true weeks later when a sow on his farm delivers a litter of stillbirth piglets, disappointing a 10-year-old boy assisting his uncle during a Thanksgiving visit. The farmer assumes bad luck was in play.

Supporter Spotlight

As Christmas approaches, the nephew gets sick at his home on the outskirts of a city. At first, his family suspects flu. But after a punishing headache and pain in his neck flare, doctors fear lethal meningitis is in play and scramble to find a cause.

No one, at least not right away, suspects the bacteria Brucella suis, which jumps from wild pigs and can kill piglets and cause a potentially serious illness called brucellosis in people.

“Nobody is thinking about that, so it takes a long time for the people involved to recognize what the problem was,” Kennedy-Stoskopf said.

To try to shift such thinking, the College of Veterinary Medicine professor collaborates with others in her field, along with physicians, veterinarians and researchers specialized in environmental, plant and wildlife topics. Members of the N.C. One Health Collaborative, they work to increase awareness of ways that the health of people, animals and the environment overlap.

They recently held the latest of a series of discussion sessions, open to the public that they host between January and April at the N.C. Biotechnology Center in RTP.

Nonfiction

People must take steps to preserve health across species, One Health enthusiasts argue, because we will always have close contact with animals. That’s likely more than ever as our global population continues to swell.

In addition, our species has always depended on animals for food. For millennia, we have sought their companionship as well.

Some critters, from tiny ticks carrying Lyme disease to the still-unknown animal host of Ebola, are existing threats. Most emerging infectious diseases worldwide today pass between humans and animals, and most of those originate in wildlife. As climate changes push animals out of longtime habitats, they may bring old diseases to new territories.

And as the menacing Zika virus is teaching the world right now, once it gets a foothold, a pathogen can expand its territory fast.

Wildlife isn’t the only sector of concern. Routine use of antibiotics at U.S. livestock facilities, for instance, that produces antibiotic-resistant germs is another example of an emerging illness link. The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention has tied one in five cases of illnesses caused by treatment-resistant germs to direct exposure on such farms or to food made there.

Feral swine are prolific breeders. Sows have approximately 1.5 litters a year with each litter averaging five to six piglets. Females can become sexually mature at 6 to 8 months of age.

The pig-to-human-sickness scenario shared with students in RTP was modeled on a real-life case in South Carolina — the mystery was solved and the boy got well. But it could occur here.

Kennedy-Stoskopf was co-author of a 2012 scientific report showing that feral pigs tested at an environmental education center in Johnston County had been exposed to Brucella suis. The news caught the attention of multiple interest groups in a state where 2,300 farms raise nearly 9.6 million hogs valued at $1.8 billion.

No one wants a Brucella species disrupting North Carolina’s hog industry.

At the discussion session, a mix of undergraduate and graduate students learned fast that preventing health problems linked to wildlife is not always simple. For example, it’s tough to control feral pigs, descendants of a mix of wild boar imported to this region for hunting, onetime farm animals and wild pigs brought here to stock hunting grounds.

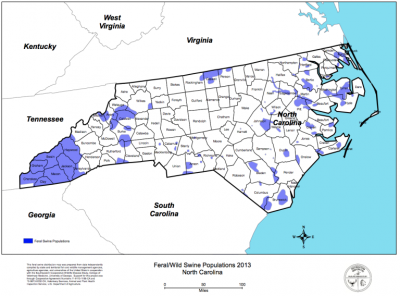

Ironically, traits people bred into their domestic ancestors long ago help wild pigs thrive in the wild today. Adaptable and robust, they reach sexual maturity young, can reproduce multiple times a year and have large litters. All of that helped them expand their territory from 17 to 39 U.S. states in recent decades.

The animals also carry many more pathogens than Brucella suis. Their groupings of multiple females and juveniles, called sounders, also damage crops, kill young livestock, damage native plants and muck up streams. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates damages at $1.5 billion a year.

Too Many to Count

“Is there a way to stop them from reproducing?” César Baëta, a master’s degree student in physiology at N.C. State asked optimistically at the One Health meeting. The answer, most emphatically on large populations scale, is no.

Feral pigs are considered invasive species in every state where they’ve been detected. An estimated population of six million produces damages totaling $1.5 billion in damage each year, says the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission doesn’t know how many feral pigs live within this state’s borders, said David Sawyer, section manager of its research and surveys division. But the commission knows their numbers have grown and considers them nuisances.

In recent years, state officials have given hunters wide rein to take the animals.

A licensed hunter can stalk them day or night, anytime of the year, with no bag limit. Electronic calls that lure the animals are allowed.

In 2015, the USDA committed $20 million a year to reduce or eliminate populations of feral swine in multiple states. That agency is spending about $380,000 a year in North Carolina.

Field staff here use thermal scopes or whatever else helps to find, trap where possible and shoot dead as many feral pigs as they can find. Carcasses get checked for disease-causing microorganisms, especially those that cause diseases that worry pork producers: swine brucellosis, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, swine influenza and pseudorabies.

A lot of the effort so far has focused in Currituck County in the northeast and Avery and Mitchell counties out west. But Keith Wehner, director of the USDA wildlife service in North Carolina, knows they and the wildlife commission, who they collaborate with, will find wild pigs in many places in between.

Wehner said he hopes his staff one day will receive an exemption from state policy forbidding the shooting of animals from the air. That would allow trained staff to board agile helicopters to spy and destroy animals from above.

“We’re using every tool we can find,” Wehner said. “Our job is control, not sport. When a landowner agrees to let us on property, we kill every single pig.”

But can such a quick-to-reproduce animal be eliminated from the wild?

“Getting to that is the long-term goal,” Wehner said.

Learn More

- North Carolina One Health Collaborative

- N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission

- U.S. Department of Agriculture

This story is provided courtesy of N.C. Health News, a website covering health and environmental news in North Carolina. Coastal Review Online is partnering with N.C. Health News to provide readers with more environmental and lifestyle stories of interest about our coast. You can read other stories about health care here.