First of two parts

WILMINGTON – State lawmakers will get to hear Tuesday about an ambitious plan to make North Carolina more competitive with other coastal states that have far more invested in their oyster and shellfish industries.

Supporter Spotlight

The N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries is set to present its reports, including a 10-year plan mandated by the General Assembly in 2015 to build and manage new oyster habitat, to the Joint Legislative Oversight Committee on Agriculture and Natural and Economic Resources when it meets at 1 p.m. Tuesday in Wilmington. The meeting will be at the Marine Biotechnology in North Carolina Building conference room in the University of North Carolina at Wilmington’s CREST Research Park at 5600 Marvin K. Moss Lane.

The division is expected to detail oyster research, recommended policy changes to boost the shellfish industry and recommendations for creating a network of oyster sanctuaries in Albemarle and Pamlico sounds. The meeting will also include a tour of a UNCW shellfish research hatchery and presentation of a beach erosion study report.

Rep. Pat McElraft, R-Carteret, is co-chair of the committee. She said Friday the plan will better position North Carolina to compete against other states’ oyster and shellfish aquaculture industries and boost commercial fishing.

“I think we’ve got a lot of catching up to do,” McElraft said. “We used to be the oyster state years ago. I’m so excited that we can start on this and hopefully this will help supplement our commercial fishermen’s income, too.”

The legislature mandated the studies last year and set a March 1 due date. The resulting aquaculture plan identifies bottlenecks, deficiencies and inefficiencies, and recommends ways to improve existing programs.

Supporter Spotlight

“The recommendations on new ways to develop the shellfish industry will benefit the state shellfish aquaculture industry and the overall shellfish resource,” according to the aquaculture plan report.

The state’s efforts to restore shellfish-growing areas have gone on for decades, but the scale of those projects is small compared to other states, including Virginia, Maryland, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas, which have invested significantly more in their oyster industries. Virginia pumps about $2 million in state funds and $300,000 from oyster use fees each year into oyster-restoration projects. Virginia’s oyster harvest increased from a low of 23,000 bushels worth $575,000 to 659,000 bushels worth $33.8 million in 2014. Maryland budgets millions of dollars each year for similar work. Gulf Coast states funnel tens if not hundreds of millions into restoration.

The division’s presentation will include recommendations for policy and statutory changes needed “to support and encourage the ecological restoration and economic stability of the shellfish aquaculture industry.”

Recommendations include funding new staff positions for shellfish programs, developing a statewide aquaculture plan and approving statutory changes to encourage federal participation and cost sharing to assist oyster growers in the state. The reports also illuminate how budget cuts in past years have hindered efforts to grow North Carolina’s shellfish and aquaculture industries.

There are no funding requests for 2016-17 in the recommendations, which detail cost estimates “for informational purposes only,” but the division makes it clear the legislature’s stated goals to expand the shellfish industry are beyond its scope.

“Promoting and encouraging this industry to expand and prosper requires focused leadership and expertise that is not part of the organizational mission of the division and which currently does not exist within state government,” according to the shellfish aquaculture plan report.

During the past 10 years, industry stakeholders have collaborated on a plan called the N.C. Oyster Restoration and Protection Plan: Blueprint for Action, but the state hasn’t provided sufficient funding to implement the plan, according to the report.

McElraft said some progress was made last year, thanks to increased funding for cultch planting, which involves spreading thin layers of oyster shells or other materials on the bottom in oyster-growing areas to provide a bed for larvae to settle and form oyster reefs. The legislature in 2015 provided $450,000 to the division to contract with UNCW to develop oyster stock to provide seed for aquaculture. The legislature also doubled the division’s funding to $600,000 for cultch planting.

Oyster Sanctuaries

The Sen. Jean Preston Marine Oyster Sanctuary Program Plan figures prominently in the overall plan to make North Carolina’s shellfish industry more competitive, and construction of new oyster reefs is a key component. The proposed sanctuary network is named for the longtime Carteret County legislator who died in 2013. The sanctuary plan is described as the best way to spend financial resources to counter declining oyster populations and habitats.

“We actually started that in our budget cycle two sessions ago, after she (Preston) had passed away,” McElraft said. “Then we realized that some of the sanctuaries were too large and it was really hard to do sanctuaries in that kind of environment. We needed smaller areas and with smaller sanctuaries we would probably produce a lot more oysters that way, too.”

The General Assembly’s mandate for the sanctuaries includes the provision that their locations be selected in areas that allow for connectivity between sanctuary areas, including 14 existing sanctuaries, and that don’t interfere with commercial trawling.

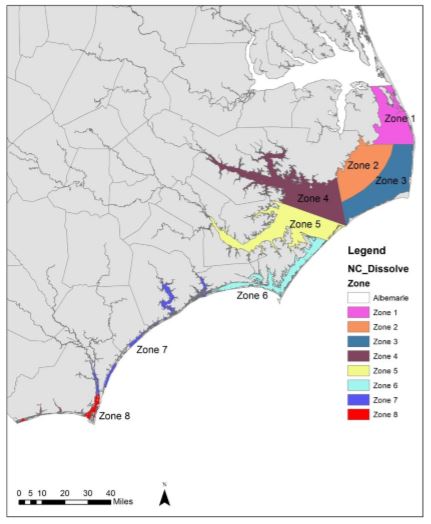

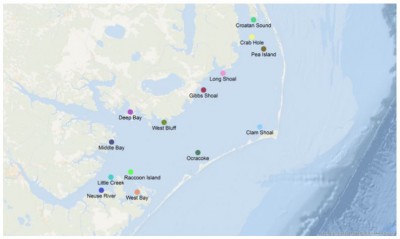

The division identified five zones in Pamlico Sound for the construction of oyster sanctuaries. The zones were delineated by combining oyster-growing areas into regions. The division is to work within each zone with commercial and recreational fishermen, scientists, universities and non-governmental organizations to determine the location and borders of existing and new oyster sanctuary sites.

The division now has 171.5 acres of oyster sanctuaries built and designated throughout Pamlico Sound. Another roughly 10 acres are funded and under construction, along with other projects in the works. Once complete, the division expects the total area to reach about 200 acres.

In contrast, recommendations from the N.C. Coastal Federation, a partner with the division on past oyster-restoration projects, call for 500 acres of oyster sanctuaries to be built by 2020. “It is unlikely the 500-acre goal will be met in the foreseeable future without additional state appropriated funding,” according to the division’s report.

The division worked with the federation in 2009-10 to use private contractors and $4 million in federal money to build about 47 acres of sanctuaries at two locations in Pamlico Sound. Based on those expenses, the division estimates that it will cost about $1 million to build 10 acres of reef, or about $30 million over 10 years to build the additional 300 acres of sanctuaries in Pamlico Sound. To help cover the costs, the division says fees from the state’s recreational saltwater fishing license and grants from the N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund could be tapped.

To reach the 500-acre goal for sanctuaries over this 10-year plan, the division estimates the program will need $1.5 million in recurring state appropriations each year to pay for construction and at least $1.5 million in additional funds each year provided through public-private partnerships with non-governmental organizations.

‘A Holistic Approach’

Division staff met with shellfish and aquaculture experts from North Carolina and Virginia, shellfish growers, non-governmental organizations, and internal division shellfish experts to develop the overall shellfish plan. Staff also met with an existing steering committee of stakeholders that oversees the implementation of the blueprint plan that covers 2015-20.

The resulting recommendations in the report are “a holistic approach” to shellfish aquaculture and restoration that links research, permitting, outreach and extension and support services of several state agencies with private shellfish aquaculture organizations and interests and non-governmental organizations.

“The success of aquaculture operations goes beyond permitting and site selection functions that have traditionally been the role of the division. Achieving and sustaining a successful shellfish aquaculture industry will depend on use of sound scientific principles, solid business planning, marketing, training and assistance from other groups,” according to the division’s recommendations.

The division recommends against using non-native oysters in the restoration effort, saying the main advantages of faster growth and disease resistance observed in past studies aren’t worth the risks to native oysters, which appear to be developing improved resistance to dermo, a parasite that appeared here when non-native oysters were introduced in the 1990s. An Army Corps of Engineers study in 2009 and a University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences study in in 2005 also reached conclusions that native oyster species were preferred.

“From an ecological perspective, evidence suggests intrinsic growth of the overall N.C. oyster population is limited by a lack of suitable habitat for the larvae to settle on, not a lack of larvae. In areas where larvae is low with suitable water quality, planting native oyster seed (young, small oysters) may be a viable restoration technique,” according to the report.

Work is ongoing at UNCW’s shellfish research hatchery to develop native species brood stock for a variety of aquaculture and growing areas in North Carolina. The legislature in 2015 provided $950,000 over the next two years for the work.

Staffing and Funding

The division recommends $175,000 in recurring, annual funding re-establish a regional lab with a lab technician for the northern part of the state. Budget cuts in 2014 forced the closure of the state’s shellfish sanitation and recreational water quality lab in Nags Head, which meant closing of several non-productive shellfish waters because all water samples must be analyzed in Morehead City. Re-opening the northern lab would provide shellfish aquaculture growers and harvesters with timely sampling of growing areas, according to the report. The division also recommends a $113,000 recurring appropriation for a shellfish pathologist and a $350,000 startup appropriation for a lab and equipment at the Center for Marine Science and Technology, or CMAST, in Morehead City.

Again, no funding requests are made with regard to the 2016-17 budget. That said, promoting and encouraging aquaculture and improving oyster stock and populations will require more money for dedicated staff in the division’s shellfish lease program, according to the report.

“While the division has the expertise to oversee and manage the permitting and administration of leases, it is not adequately funded to do so,” according to the report. The program’s annual budget is $4,526.

The division recommends funding four full-time positions, including a licensed surveyor position, with total yearly salaries of about $120,000 and recurring operating funds of $200,000 to a dedicated shellfish lease program within the division.

The division recommends doubling the current $200 shellfish bottom lease application fee to help offset the cost of administrating the lease, which costs the state about $3,000 or more per application, depending on the size of the lease. “An increase in application fees would still be less than the Virginia initial lease application of $625 which includes a survey and initial marking,” according to the report.

Changes to bring all shellfish leases into the same renewal period, simplify the application process for growers and increase penalties for theft on shellfish leases are also recommended.

Steps toward water-quality improvements are also included in the division’s report, including long-term, dedicated funding sources, such as user fees and shell taxes, “to allow resource stakeholders to contribute to the costs of oyster restoration and associated improvements in water quality.”

The division recommends using Virginia’s Marine Resource Commission as a model. That state set up a panel to implement shellfish resource user fees to provide stable funding for oyster reef restoration at about $300,000 annually, in addition to the roughly $1.2 million in yearly state appropriations, to support oyster cultch planting and restoration. Licensed shellfish harvesters, shellfish growers, dealers, shucking houses and shippers contribute to the fund.

“Using a program similar to Virginia, North Carolina could expect to generate between $130,000 and $150,000 or more annually for oyster enhancement projects, depending on the number of participants and current license structure,” according to the report.

Other recommendations include expanding use of private hatcheries supply seed to shellfish growers and setting up a $250,000 recurring fund to provide up to 75 percent of the costs for nongovernmental organizations, colleges and universities developing small, less than two-acre, oyster restoration sites.

Beach Erosion

The joint committee will also get its first look at the N.C. Division of Coastal Management’s report on beach erosion, which was also mandated by the legislature last year. It outlines strategies based on a review of historical N.C. studies, lessons learned from other coastal states, the agency’s experience and public comments.

Legislation passed in 2015 requires a 2016 update to the N.C. Beach and Inlet Management Plan, which was originally published in 2011.

The report calls for continued streamlining of permitting for beach projects at the federal and state levels as a way to decrease permit-processing times, permitting costs and emergency situations.

The report recommends formal beach management at the local level, including hiring staff, collaborating with neighboring beach communities and creating dedicated sources for beach-management funding.

It also calls for a dedicated state agency staff for support and technical assistance for local efforts.

The report also recommends “sensible construction setbacks to account for beach erosion and shoreline migration, taking into account the life expectancy of the structure” and other considerations.

Beneficial use of suitable dredged material was a stated priority, with continued cooperation with the Army Corps of Engineers.

Learn More

Tuesday: Looking to Virginia