Rachel Carson was delighted by the variety of shorebirds that she saw in the salt marshes around Beaufort. Here’s just a sampling as seen through the lenses of Jared Lloyd’s camera.

Last of two parts

BEAUFORT — In his autobiography, Benjamin Franklin famously declared that it was “So convenient a thing to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.” Such was the driving ideology behind Manifest Destiny. The rise and fall of empires are hinged upon these words. As is the lengths to which we will go in order to rationalize our pursuit of money and profit.

Supporter Spotlight

America, in the 18th and 19th centuries, was seen as a ripened fruit ready to be plucked. With maps that still contained the phrase Terra incognito scribbled out across blanks spots, this was a land of seemingly inexhaustible resources. Great forests stretched further than a man could walk in a month’s time. Schools of fish leaped into boats on their own accord. Waterfowl along the coastal marshes blackened skies during the migration. And it was such images of America’s low hanging fruit that ultimately drove the colonization of and immigration to this New World.

Take a moment to consider this. If it was inexhaustible natural capital that was a driving force for the creation of America’s colonies, and the ambition to exploit and profit from such resources fueling the motivations of those who risked everything to travel oceans to reach these shores, then what does this say about the ideological seeds from which our culture and civilization grew?

Such notions are not lost to the primary sources of history. Upon returning home to his native France, Alexis Tocqueville compiled a book that today continues to stand as one of the most important historical accounts of pre-Civil War American society – Democracy in America. In discussing the general mindset of the people that he met on his travels in 1831, Tocqueville observed, “the American calls noble and praiseworthy that ambition which our medieval ancestors used to describe as slavish greed …” He explains that “This love of money has, therefore never been stigmatized in America and … it is held in high esteem.”

This was the ideological underpinnings from which natural resources were exploited and profits were made. And it was this backdrop from which the commodification of nature would become rationalized, institutionalized, protected by the fullest extent of the law and practiced with religious fervor. To commodify nature effectively turned everything from fish, fowl, forests and rivers into inanimate lifeless items for sale. To think of such things as resources or capital effectively shrink wraps and sticks a smiling label on such “products” and “goods,” to borrow a modern-day concept, forever severing their connection to a once living, breathing member of this world. Fish becomes seafood. Forests become lumber. And all of it is for sale in the land of milk and honey.

Then Along Came Rachel Carson

When Rachel Carson first came to Beaufort in the 1930s, it was on the heels of a paradigm shift in American culture and politics. The wanton destruction of 19th century had not been without its detractors. Emerson and Thoreau helped bring about an American romantic movement in the early part of that century, followed by artists such as the landscape painter Thomas Cole. In 1864 George Perkins Marsh published his groundbreaking book Man and Nature that for the first time rationally and scientifically detailed the effects of America’s fire sale of nature. And all of this would culminate at the turn of the 20th century in Theodore Roosevelt, a self-taught ornithologist and naturalist and then president of the United States, declaring that “The United States at this moment occupies a lamentable position as being perhaps the chief offender among civilized nations in permitting the destruction and pollution of nature.”

Supporter Spotlight

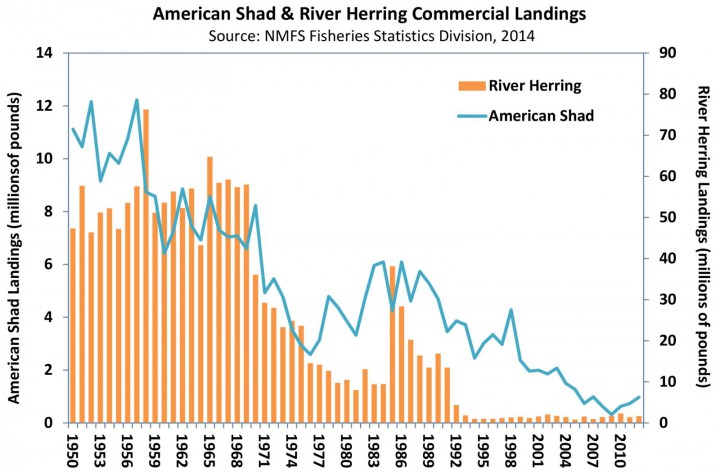

Of all the hidden worlds that Carson reveals to us in her first book, Under the Sea Wind, of all the species that she details the daily dramas of life and death, the American shad stands as an important example of how the whims of the market can have a ripple effect through entire ecosystems and human communities that depend on them. Ironically, nearly every species that she depicts in her books can stand in as an example of this, but it is the decline of shad that had the greatest impact on North Carolina.

In Under the Sea Wind, Carson paints a picture of an emblematic moonlit night in the month of May, where fisherman of various sorts fought both nature and each other for access to the annual spring run of roe-filled shad moving into the estuaries and up the rivers. Mobile gill netters argued bitterly with the workers of stationary pound nets for a piece of the action each night. The west bank of the North River in eastern Carteret County was chocked so tightly with impoundment nets that navigation itself was nearly impossible, and to set a gill net meant to sabotage other fisherman in the process.

Yet, what is not revealed in her story, is that these watermen were fighting for mere scraps left over from the great feast that was once the spring shad run in North Carolina.

The great spawning runs of fish across North America are by and large a thing of the past now remembered only in accounts from a time before markets got a hold of them. The one notable exception, of course, is salmon, and only in British Columbia and Alaska due to some of the most austere commercial fishing regulations on the continent. Whether we are speaking of American shad runs on the Roanoke River or Yellowstone cutthroat trout on the Snake River, the scenario was quite similar to the picture we have today of salmon in coastal Alaska with both man and beasts lining the riverbanks to reap the harvest of one of nature’s most extraordinary bounties.

The Founding Fish

In North Carolina, the American shad was the lifeblood of the land, driving both ecosystems and settlement patterns of natives and colonists alike. A hundred miles from the coast, the density of these shad runs meant that little more than a basket was needed for scooping fish from the rivers and packing barrels with a year’s supply of protein. This was a subsistence way of life that stretched all the way to the foot of that Appalachian Mountains where shad were once harvested as far west as Wilkesboro – a run of 450 miles upriver from the coast.

All of this changed when shad become a commodity, a marketable resource. More shad meant more money and in short order commercial fisherman began stretching seine nets across entire river mouths effectively cutting off entire shad runs to all points west. Whole ecosystems struggled to function. Upriver, poor farmers and wealthy plantation owners alike banded together to declare that shad was the “common rights of mankind” for which they were being deprived of by the greed of the few.

What had once been a free and natural bounty that most of the North Carolina colony had come to depend upon, was now a commodity for which most of the colony was forced to purchase. Some historians have argued that it was the destruction of the shad runs by the likes of commercial fishing operations along the coast that helped force a market economy on North Carolina, pushing the colony toward large-scale agriculture and dependency on the slave trade.

By the mid-1700s, the writing was already on the wall as to how all of this would ultimately play out. In 1764, North Carolina’s colonial assembly began the first attempts at putting reigns on the coastal fishery when they tried to ban the use of double seine nets by “avaricious persons.” Gov. William Tryon, the same governor that crushed the North Carolina Regulators, claimed this to be “destructive of the spirit of industry and commerce” and set about vetoing any bill that attempted to ban, limit or regulate the commercial seine netters. Coincidentally, the famed Tryon’s Palace sits along the Neuse River in New Bern, where many commercial seine netters hailed from.

Political positions wax and wane, and the natural lifespan of politicians necessitates change to some degree. In 1787, with the free-market evangelist Tryon out of the picture, North Carolina enacted a general statute authorizing counties to appoint commissioners for the purposes of inspecting rivers and streams to make sure that at least a quarter of the channels was left open for runs of fish during the spawning season.

Try as the state may however, such measures had already come half a century too late. Between over-harvesting at the coast and the mills damming up creeks and rivers inland, populations of American shad began to plummet. Half of the state had long turned away from its dependency on spring shad runs and even coastal markets were beginning to look to other species of fish such as mullet, given the sad state of shad populations.

By 1852, the Select Committee on Fisheries reported that North Carolina’s rivers which were once overflowing with shad in the springtime were now virtually empty. The fishery had been abandoned on most of the principle rivers. Only the Chowan River and Albemarle Sound could the commercial shad fisherman still be found, according to the Select Committee’s report “where seins are used of more than a mile in length and thousands of drag and set nets dot over the waters in every direction” – all desperately clinging to a fish and a way of life that they had come to destroy.

The story of North Carolina’s shad fishery is not unique. Similar stories played out along the Eastern Seaboard from Florida to the Canadian border. And it was the overfishing and complete collapse of certain fisheries like shad that would lead to the creation of the U.S. Commission on Fish and Fisheries in the Department of Commerce in 1871 for the purpose of investigating why fish stocks were declining. Shad populations, it was discovered, had declined 99 percent by then.

It is said that drastic times call for drastic measures and by the following year, a fortune was being spent on the construction of fish hatcheries in order to artificially stock rivers to keep the fishery alive. In 1873, North Carolina’s first hatch of some 45,000 shad were released in the Neuse River from the site of the new federal fish hatchery in New Bern, ironically near Tryon’s Palace.

Feds to the Rescue

Federal tax dollars went toward building shad hatcheries near the mouths of most of the major shad rivers in North Carolina. For about a decade even the state itself got into the business of trying to help rebuild the shad population, but gave up in 1885, washing its hands of responsibility for artificially stocking rivers.

Over the coming years, some 4 billion baby shad would be hatched and released in waters up and down the East Coast in a desperate attempt to save the species from oblivion. Yet even now, after 142 years of annually raising and releasing shad into the waters of North Carolina to compensate for the fire sale that once took place here, the shad population is “stable but low,” according to the latest assessment. North Carolina is one of the few states that still allows for a commercial fishery for shad and two hatcheries continue to operate for this reason – one in Edenton, the other in Watha in Pender County, which dump millions of dollars and shad into trying to keep this industry artificially alive.

The U.S. Commission on Fish and Fisheries underwent a name change to the Bureau of Fisheries in 1903, which employed Carson when she arrived in Beaufort. And it was in Beaufort, or more specifically, Piver’s Island, that the second-largest bureau laboratory was located – established as the southern counterpart to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts and strategically located for its proximity to what was the most important commercial fisheries in the South.

Shad were not the only species that toed the line of extinction by the end of the 19th century. Nearly every single species described in Under the Sea Wind came a hair’s breadth away from never making it into Carson’s book for the simple fact that they almost didn’t make it to the century.

At the time that Carson arrived to the area, a team from the bureau in Beaufort was studying local population of diamondback terrapin, a species of turtle that Carson so elegantly described in her book. Throughout Colonial times and into 1800s, terrapins were seen as a nuisance species by commercial fisherman in North Carolina’s estuaries as they were so numerous that nets would oftentimes break under the weight of so many turtles. For this reason, an entire wagon load of these beautifully colored turtles of the salt marsh sold for a single dollar. By the 1920s, however, terrapins were so rare that a dozen of these turtles fetched $90 on the market in North Carolina and significantly more elsewhere. For a brief time, the bureau attempted to establish a diamondback terrapin hatchery in Beaufort, but by the end of World War I, the wild population was so low that the hatchery was closed and the idea abandoned.

Such destruction was not limited to life under the sea of course. Even the birds found themselves at the fate of the market. Looking back into the pages of history, we find that the first wave of outside interest along our coast was not for the fish but for the waterfowl. As Union soldiers filtered their way out of North Carolina and back north again after Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, they took with them tales of inexhaustible numbers of ducks, geese and swans that blackened the skies over the sound country during fall migration.

Punt Guns and Ladies’ Hats

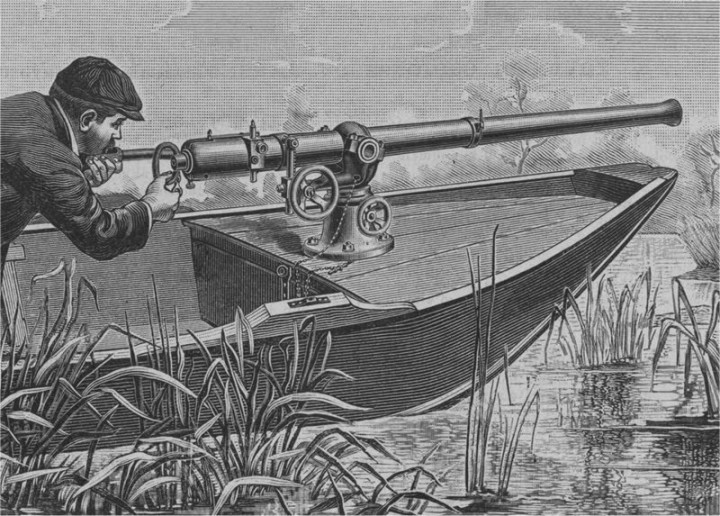

The first gunners who came south to confirm such stories were the wealthy captains of industry. Names like Carnegie, Mellon, Morgan and the Roosevelt family took great interest in the sport hunting opportunities along the barrier islands and sounds. But soon followed the market hunters, who employed the use of disastrous weapons called punt guns. These guns were little more than homemade cannons. Technically a shotgun, punt guns were often 10 feet long and so heavy that they had to be mounted to the front of the boats that gave them their names. These guns were loaded with enough shot that it was not uncommon to take out 50 – 100 birds in a single blast. Nets were strung between boats to scoop up the thousands of dead birds floating on the water’s surface at the end of a morning’s hunt.

The nuptial breeding plumes of egrets were once worth more than their weight in gold, leading to only a small handful of breeding colonies that survived the insatiable women’s fashion industry. Brown pelicans were shot and sold with such fervor that their entire eastern population had been reduced to one single breeding colony off the coast of Florida for which President Theodore Roosevelt protected as the first National Wildlife Refuge. Black skimmers, who figure prominently in Under the Sea Wind, to this day are still a threatened species in North Carolina thanks to egg harvesters that would annually raid every nest they could get their hands on – colony sizes were once officially measured in the number of bushels of eggs that it contained.

From red wolves to red-cockaded woodpeckers, if it were not for a paradigm shift in America around the early 20th century, so much of the incredible diversity of this state and nation would be little more than sketches and watercolor paintings in obscure notebooks of 19th century naturalists.

This was the world in which Rachel Carson began her nature writing career within – one where stories like those detailed in the report from the first expedition to Roanoke describing natives stopping to fill multiple canoes with fish in a matter of half an hour to offer as gifts to the English ships were now a thing of the past. By the 1930s these stories were just that – stories. Such depictions were pure fiction, abstract words and concepts scribbled upon paper documenting a fantastical world of plenty that could only be dreamed of. But this was also a world in which the words of John Muir had been taken to heart, where giants like Teddy Roosevelt could come to power and bring about sweeping political change toward the natural world.

Rachel Carson waded the shallows around Bird Shoal when America’s culture had just pass through a great crossroads. Our society had been left with a decision to make at the outset of the 20th century: Would we allow for species such as the American shad, great egrets, diamondback terrapin, and black skimmers to slip over the edge of oblivion? Was this the legacy that we wanted to leave for future generations – a world devoid of that which both our nation and cultural identity had been built upon? Thankfully, the collective voice of America had cried, “No.”

Rachel Carson began her career as an author allowing her creative genius to drift across the salty waters of Back Sound. The words she set down in books like Under the Sea Wind revealed to the nation a world unseen, largely unstudied, as unknown as outer space, yet as familiar as the old oak tree in the front yard. She would end her career by giving teeth to a movement that stood to shake the very foundation of America’s industry to its core. A smallish, soft-spoken woman, who never married, cared for her aging mother and orphaned niece, who wrote in first person about sanderlings and mackerel, who was entranced by the sea and the natural world, who would be labeled a communist operative in the age of McCarthyism for writing her book Silent Spring, who would be investigated by the FBI, stalked by men in dark suits hired by chemical corporations, and die of cancer – that plague of the 20th century she so passionately warned about. This was Rachel Carson. And her life and legacy lives on in the descendants of black skimmers, ospreys, and diamondback terrapins of North Carolina that she would bring to literary life in Under the Sea Wind.