HOLDEN BEACH — Two environmental groups weighed in this week on this beach town’s plan for a terminal groin to combat erosion. One group focused on the project’s possible effects on birds while the other criticized the proponents’ science and the environmental review process.

The terminal groin proposed for the east end of the island will have “significant and lasting” ill effects on birds and other wildlife and fail to stop erosion at the east end of the beach, the National Audubon Society’s state office noted in its comments on the project. The N.C. Coastal Federation also submitted comments this week, mainly taking issue with procedural and scientific shortcomings of the study. The 45-day comment period on the study made public in August ended Tuesday.

Supporter Spotlight

Walker Golder, Audubon N.C. deputy director, submitted the comments Monday to the Army Corps of Engineers’ Wilmington office regarding the draft environmental impact statement, or DEIS, for the plan known officially as the “Holden Beach East End Shore Protection Project.”

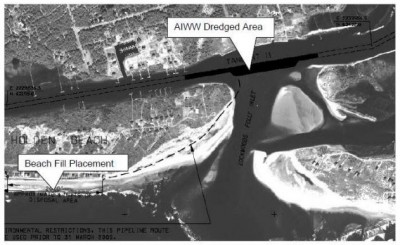

The Brunswick County beach town’s preferred plan, known as Alternative 6, is to build a roughly 1,000-foot-long terminal groin at the east end of Holden beach and begin a beach renourishment regime that would place between about 120,000 and 180,000 cubic yards of sand on the beach. The sand would come from a site at the crossing of the Intracoastal Waterway and Lockwood Folly Inlet. Renourishment would be needed about every four years, according to the DEIS.

“This alternative, as well as other alternatives that include the construction of a terminal groin or any other hard structure … will have significant and lasting negative direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts on birds and other wildlife that depend on the dynamism of mid-Atlantic coastal inlets at critical points in their life cycles,” Golder writes in the letter.

The Coastal Federation said in its letter the Corps cannot issue a final environmental study until it complies with the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, requirements and other federal laws.

“The Corps has failed to comply with the requirements established by NEPA and with other federal laws. The DEIS is replete with deficiencies that must be addressed,” according to the Coastal Federation’s letter.

Supporter Spotlight

The organization’s letter says the Corps’ study does not provide an objective analysis, rather it provide justification for decisions already made.

“The … (Corps) does not provide the public and decision-makers with a thorough and comparable analysis of reasonable alternatives, thus confining the public information to narrow, selective and targeted information that supports only the preferred alternative,” according to the Coastal Federation’s comments.

Supporters of the project say it’s needed as a long-term solution to the erosion problem that has claimed more than two dozen homes on the east end of the beach during the past 25 years. Some environmental advocates say they also see potential benefits.

Holden Beach Mayor Alan Holden said he and other town officials are sensitive to the concerns about birds and wildlife, but also bear the responsibility for protecting taxpayers’ investments and the infrastructure on the island. There’s a balance, Holden said.

“We try to do everything we can to comply with all regulations and take care of our natural assets. We’re not going to do anything to jeopardize that, knowingly,” Holden said. “As far as I know, we are in good standing with all of the environmental departments that monitor those kinds of things and we want to continue to stay in good standing.”

Holden said the east end of the beach has long a trouble spot for erosion but efforts to stabilize the beach have been somewhat successful. The groin would further stabilize the beach, he said. The strand meets the criteria as an engineered beach, as defined by federal agencies that regulate renourishment projects.

Working to protect the homes all along the nine miles of beachfront is important to the local and statewide economy, Holden said. “We have to do all we can. We’re trying to work with nature; we’ve studied drifts, east and west, and we think we’re ion the right path,” he said.

Those who oppose terminal groins say they may help stop erosion in the areas where they are built but usually cause increased erosion farther down the beach because of the interruption of the natural movement of sand.

Terminal groins were prohibited in North Carolina for 30 years until 2011, when the N.C. General Assembly passed a bill that allowed up to four “test” terminal groins to be built on state beaches. Holden Beach was one of four coastal communities to apply to the Army Corps of Engineers to build a terminal groin under the new law. The other applicants were Figure Eight Island, Ocean Isle Beach and Bald Head Island.

This year, the legislature, without waiting to see how the “test” projects worked – construction has begun on only the Bald Head Island structure, so far – allowed two more terminal groins to be built, raising the total number to six. The latest provision specifies the locations for the two additional projects as North Topsail Beach and Bogue Inlet.

Environmental groups generally oppose terminal groins, saying erosion is a natural process and stopping that movement of sand has ill effects elsewhere along the beach. That’s a focal point in Golder’s comments on behalf of the Audubon Society.

He writes that the DEIS takes a “make them go somewhere else” approach when addressing the effects on birds of the preferred alternative and most other alternatives. “It perpetuates the common misconception that breeding and non-breeding shorebirds and waterbirds have alternative places to go when habitat is lost and that, because birds have wings, they will simply move somewhere else,” Golder notes. “The truth is, the birds are already occupying alternative locations. They have been relentlessly forced to abandon high-quality habitats throughout their range because of habitat loss and degradation.”

According to Golder, the loss of habitat is reflected in the elevated conservation status of many of the bird species that depend on inlets and barrier islands, including those that depend on Lockwood Folly Inlet. Nearly all can be found on state or federal lists of threatened and endangered species.

Terminal groins are designed to stop the movement of sand along the shore. Golder cites studies that show terminal groins actually accelerate erosion of the shoreline downdrift of the structure and notes that more frequent renourishment would be needed.

“The near certainty that Holden Beach will need to mine sand from Lockwood Folly Inlet and replenish the downdrift beach on Holden Beach more frequently than every four years has not been accurately assessed in the DEIS,” according to Golder.

Golder also cites threats to sea turtles from renourishment. Tony Marwitz, president of the Holden Beach Turtle Watch, or Turtle Patrol as the volunteer organization that works to protect sea turtles is better known, disagrees with Golder’s assessment. Marwitz, who has been active in the group for nearly 20 years, said renourishment isn’t a threat.

“Renourishment can’t be done during nesting season, they’re prohibited from doing that,” Marwitz said. “I’m not concerned about beach renourishment affecting turtle nests.”

Nesting season runs from May through October. That’s when female turtles dig nests to lay their eggs along the N.C. coast. According to the N.C. Fish and Wildlife Service, sea turtles dig about 775 nests on N.C. beaches each year, and all sea turtles that nest on U.S. beaches are listed as threatened or endangered. This season saw 53 nests on Holden Beach.

The Turtle Patrol and its roughly 65 members operate under the authority of the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, searching during nesting season for turtle crawl tracks in the sand and following the path to find the eggs. If the nests are in an unsafe location, the group moves the eggs to a safer part of the beach. There, the new nest site is covered with a protective grating and marked off with stakes, ribbons and warning signs. The group then continues to monitor the nest for the next 50-70 days of incubation until the eggs hatch, at which time patrol members begin nightly watches until the hatchlings make it safely to the ocean.

Marwitz said the terminal groin project would benefit turtles and other wildlife by stabilizing the habitat.

“Our beach has changed drastically. It’s mobile with a fair amount of erosion. We’ve had nests erode, literally get washed away, during storms. Anything for a stable, more consistent beach would be much more beneficial to the turtles,” Marwitz said.

Erosion is a problem on both ends of the beach, Marwitz said, but the problem is most severe at the east end.

“If nests are laid there, we have to move them. We can’t really leave them there because there’s no beach. The tide goes up to the dune line,” he said.

A greater area of sand would benefit shorebirds, as well, Marwitz said. “I am assuming the terminal groin will do what the people tell me it will and build a more stable beach,” he said. “I don’t see how the construction of the terminal groin can be detrimental to the turtles or the birds. The purpose of the terminal groin is to make the habitat larger and more stable. How can that be a detriment?”

It could be, depending upon where the new area of erosion is after the terminal groin is built. Golder points out that terminal groins and other coastal engineering projects affect inlets and adjacent beaches. The environmental study falls short in addressing those effects, according to Golder.

“The DEIS fails to cite the applicable, most recent scientific literature and fails to accurately describe the impacts a terminal groin, beach renourishment, and inlet channelization would have on Lockwood Folly Inlet and adjacent areas. Some of the impacts that are insufficiently addressed are the narrowing of downdrift oceanfront beach, loss of sediment from the inlet system, impacts to spits at ends of adjacent islands, loss of critical wildlife habitat, and cumulative impacts of the alternatives,” according to Golder.

Golder notes it is well documented that terminal groins accelerate erosion of the shoreline downdrift of the structure.

The terminal groin’s effect on sand movement would also affect fisheries and other wildlife, recreation and the local economy, according to Golder. “These impacts and the loss of saltmarsh resulting from removal of sand from Lockwood Folly Inlet have not been assessed for the preferred or other alternatives in the DEIS,” Golder writes.

The inlet has been a problem for mariners for years and requires nearly annual dredging. The channel was most recently dredged in February-March this year. By June, mariners were reporting shoaling had returned with only mid- to high-tide passage recommended.

Holden said the inlet crossing is a big concern locally and especially for the Army Corps of Engineers, which is charged with maintaining navigation.

“It’s just about impossible for barges to navigate from the north end of North Carolina to the south end through the waterway these days,” Holden said, adding that a project that mutually benefits the Corps and the beach town is a good deal for taxpayers. He said there is a history of cooperation among various interests involved.

“If we all work together like we’ve been doing its better for everyone,” Holden said.