Ron Sutherland knew before entering middle school that he wanted a career protecting wildlife, but he couldn’t have guessed that it would one day require sneaking around to place 600 pine seedlings in red cups in the driveway of a university chancellor.

Guided by a conservation ethic learned in the Boy Scouts and nurtured by writings of Aldo Leopold, Fred Cubbage took a different path to that driveway.

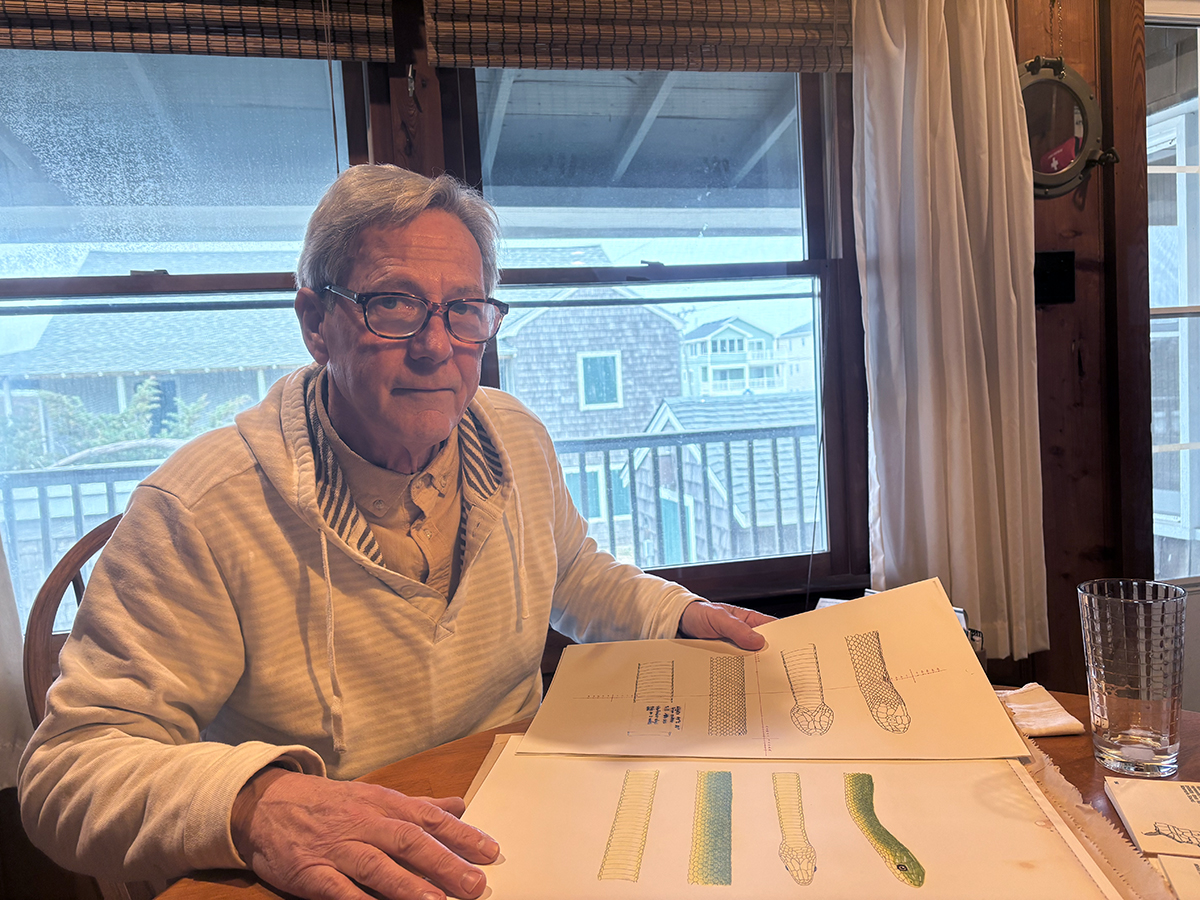

Supporter Spotlight

Together, they saved a forest.

Sutherland and Cubbage led the statewide campaign that probably kept N.C. State University from selling its 79,000-acre Hofmann Forest in Jones and Onslow counties to developers. They both recently won Pelican Awards from the N.C. Coastal Federation for their effort.

Walking the Woods

Sutherland had led a relatively normal life as a conservationist and wildlife biologist before the Hofmann battle began in 2013. He grew up in Cary and spent a lot of time camping with his parents.

“But I think what really started me was, when I was, I don’t know, somewhere between 6 and 8, there was a big area of woods behind our neighborhood, and one day somebody cut the whole thing down,” Sutherland recalled. “I really, really didn’t like that.”

The woods he loved, where he played constantly and fed reptiles and nurtured a budding science addiction, became a church parking lot and his conservation inclination grew with time, as he watched the incredibly rapid development of Cary.

Supporter Spotlight

When he entered N.C. State, Sutherland narrowed his choice of majors to biology and forestry. He chose the former and got his degree.

He received his master’s at University of Wisconsin at Madison, but the Old North State – and its warmer weather – pulled him back south, to Duke, where he earned his doctorate and met his mentor, professor Jon Terborg, a tropical ecologist.

“He was a conservationist and a big advocate for conserving forests,” Sutherland said. “He was a very big inspiration.”

Inspired by Terborg, Sutherland decided to actually conserve something, not just teach others to do it. Terborg was on the board of directors of the Wildlands Network, a Seattle-based international organization that was looking to expand to the Southeast. Sutherland took a job with the group in 2008.

But in early 2013, everything changed when he heard that Hofmann Forest might be for sale. Sutherland read a news article a short time later that quoted Cubbage as saying the proposed sale was a bad idea.

“So I called Fred and asked him what was going on and suggested some kind of a protest,” he recalled. “We got this idea …”

Iowa and Ding Darling

Cubbage’s path to Hofmann began in Iowa, where he was born and raised. He traces his conservation ethic back to scouting and to books of old editorial cartoons he saw and read as a teenager in the 1960s by the legendary Jay “Ding” Darling, who won two Pulitzer Prizes for work at the Des Moines Register in 1924 and 1943.

“He made a big impression on me,” said Cubbage.

But he also recalled the influences of fellow Iowans Aldo Leopold – who wrote the classic, “A Sand County Almanac,” in 1949 – and John Lacey, a Republican U.S. congressman who sponsored a bill in 1900 that prohibits trade in wildlife, fish and plants that have been illegally taken, possessed, transported or sold, and imposes civil and criminal penalties for those who violate the rules and regulations.

Cubbage earned his bachelor’s degree in forestry from Iowa State University, then moved north to the University of Minnesota, where he got his master’s in forest policy and a Ph.D. in forest economics.

Like Sutherland, Cubbage then fled south to escape the cold weather, first to U.S. Forest Service in New Orleans, then to the University of Georgia, then in 1994 to a post as head of the Department of Forestry at N.C. State. He wrote a widely used forestry policy textbook and stayed on as a professor at N.C. State after dropping the departmental administrative duties in 2004 because he wanted to spend more time teaching and doing research.

Along the way, Cubbage had participated in a couple of successful protest efforts, first to stop the Army Corps of Engineers from flooding a state park and later to halt N.C. Department of Transportation plans to build a road that would bisect a university research forest in western Wake County.

The Fight for the Hofmann

The idea that Cubbage and Sutherland hatched in 2013 involved pine saplings and paper cups. Sutherland drove to a local nursery and got 600 saplings that the owner was going to throw out, and his two older kids helped put them in the cups.

“Apparently, word of it got around,” Sutherland said, “but they didn’t know exactly where we were going to do it. So a few of us met at the Raleigh Farmer’s Market near campus, and we had a borrowed trailer, and we drove to the chancellor’s and just made sort of a miniature forest in the driveway.”

The stunt got attention, but not just from campus police and officials. Word spread of a brewing battle, and Sutherland and Cubbage sued the university to require an environmental study of the sale.

A break came when Sutherland received a “prospectus” that the forest’s future owner, an Illinois agricultural corporation, was using to raise money for the purchase. Although the school had insisted that the buyer was going to conserve much of the of the forest, the document dealt enthusiastically and convincingly with a plan of widespread conversion of forestland to corn crops and the construction of shopping centers, residential developments and golf courses.

Sutherland and Cubbage began sending out emails, talking to the media and placing signs all over town and beyond.

“We got some donations and we ordered 400 ‘Save Hofmann Forest’ signs, and somehow there was a mistake and we got 800,” Sutherland said. “So we took signs everywhere, from Winston-Salem and Greensboro all the way to the coast. They (N.C. State officials) couldn’t miss them.”

Pressure mounted and the $150 million sale to the Illinois firm fell through. Then, the university turned to a plan to sell 56,000 acres of the forest to Resource Management Service of Alabama, a timber-management company, and the remaining 23,000 acres to the Illinois company. But that deal also fell through.

Finally, in March, the school announced it would focus on conserving much of the 79,000-acre forest, maintaining a working forest and providing access to university researchers and students.

Practice What You Teach

Cubbage knew that joining Sutherland and others in a lawsuit to stop the Hofmann sale was a big step that he considered carefully because he was suing his employer.

“I was 61 or so and I had tenure, and I kept remembering a mantra I had read and kind of adopted,” Cubbage said. That saying, from the Catholic ceremony to ordain deacons, is, “Believe what you read, teach what you believe and practice what you teach.”

Nothing, Cubbage decided, could be more appropriate in a university department that preached sustainability and wise use of natural resources. And the potential destruction of Hofmann, for profit, certainly seemed hypocritical. So he went all-in on the effort to stop the sale with full knowledge of the difficulties it could cause in his professional life.

Cubbage recently looked back at the emails and files he has saved so far in the Hofmann saga. He counted 6,500 emails and 1,024 document files. He still did his job at the university, but the fight consumed most of the rest of his life. And it has come with a cost. The state’s university system has recently changed its tenure policy, giving the school administration the final decision on dismissing faculty. That could quell opposition, said Cubbage, who is now 63 and would like to continue working to age 70 or beyond.

But it’s all been worth it, Cubbage said, if the Hofmann is ultimately preserved, both for its environmental and ecological value and for student use. “We all stopped the sale, although it could still happen sometime down the road,” he said. “You have to feel pretty good about the outcome, so far.”

The university’s Endowment Fund and Natural Resources Foundation, which technically own the forest, are to negotiate sales of easements and leases to the Navy and Marine Corps for training. They will also investigate selling a multi-decade timber deed on close to 56,000 acres of existing pine plantation, with requirements for certified sustainable forestry practices, and negotiate conservation easements for about 18,000 acres known as the Big Open Pocosin. The university may also sell the current 1,600-acre farm for continued agricultural use and two mitigation banks, totaling about 450 acres, for continued mitigation use.

The Conservation Fund, a national organization with a state chapter headed by Bill Holman, has been hired to negotiate those deals.

Sutherland and Cubbage, however, are still engaged, and hope time and effort will convince N.C. State not to sell off Block 10, the piece of the Hofmann closest to N.C. 17, the main highway between Jacksonville and New Bern.

It’s a key part of a crucial wildlife corridor that links Hofmann to forested areas of Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, Sutherland said, and would be a nice state park. It is, he said, something the legislature could buy, probably for about $15 million, with some of the $400 million-plus budget surplus. Or someone else could buy. At any rate, there’s probably still another battle to fight.