On April 20, 2010, a cascading series of errors resulted in the largest oil disaster in history.

The Deepwater Horizon, a British Petroleum well 50 miles offshore in the Gulf of Mexico in 5,000 feet of water, exploded and began discharging oil. The federal government estimated that by the time the well was finally capped almost five months later, 4.9 million barrels of oil, or 210 million gallons, had leaked into the Gulf. A 2015 court proceeding put those numbers at 3.19 million barrels, or 134 million gallons.

Supporter Spotlight

The report by a national commission appointed by President Barack Obama to determine the cause of the worst oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry put the blame on a host of human and mechanical mistakes and failures. BP tried various measures to stop it, used 1.86 million gallons of a toxic chemical dispersant and eventually spent billions of dollars on cleanup, mitigation and compensation efforts that continue to this day.

Hundreds of miles of Gulf shoreline were oiled. Beaches were closed because of health threats, thousands of birds and marine mammals were sickened or killed and tourism and commercial fishing were disrupted in countless communities heavily dependent on them.

Time passed. The Gulf and its shoreline at least partly healed. And, eventually, in a world and nation still heavily dependent upon petroleum, thoughts of tapping the oil and gas believed to be in the Atlantic became less unpalatable. Finally, in July 2014, the Obama Administration, committed to an “all of the above” energy strategy, announced that it had given the go-ahead for a program that might lease tracts of the Atlantic beyond 50 miles from shore, including off North Carolina, for oil and natural gas drilling.

Could It Happen Here?

The announcement triggered praise from many, but the words on the lips of countless others were largely only two: “Deepwater Horizon.” And as companies gear up to test the waters off the Tar Heel state for oil and gas, the lingering question is: Could it happen here?

Harvey Seim, chairman of the Department of Marine Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a man who was on the Deepwater Horizon response team, said that the 50-mile buffer offers some protection from potential problems if a disaster were to happen north of Cape Hatteras, in the area believed most likely to hold commercially significant undersea oil and gas deposits.

Supporter Spotlight

But, he said recently, there’s no guarantee, and there are many factors that would come into play, the largest of which are the position and flow of the Gulf Stream at the time accident and afterward.

The river of water flowing north off the East Coast could in theory take spilled oil thousands of miles to the English coast … or just a few miles away to Cape Hatteras.

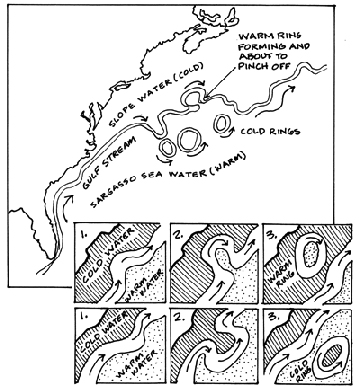

“There are eddies, or rings, off the Gulf Stream every week,” Seim said. “They push water onto the continental shelf. If it (a spill) happens north of Hatteras, the chances are lower than south of Hatteras, but there is definitely chance oil will get in to our shores.”

Eddies off the Gulf Stream – although farther south, near Carteret County – brought North Carolina’s first known toxic red tide ashore in 1987, he noted.

The dinoflagellate algae bloom came in on Halloween day, brought from the Gulf off Florida, where red tides are common. While it’s a wholly different kind of event than an oil spill or oil well blow-out, it illustrates that potential transport mechanism.

Generally speaking, the Gulf Stream passes closest to shore off North Carolina’s Outer Banks. The exact distance varies, but can be as little as 12 miles.

Oil on the Beaches

Larry Cahoon, a marine biologist at UNC-Wilmington, said it was once thought highly unlikely that oil from a spill outside the Gulf Stream, north of Hatteras, would make it to the N.C. shore and its estuaries. But more recent studies indicate there is at least a 30 percent chance.

“I wouldn’t put a number on it,” Seim said, “and it depends on the character of the oil, and the wind direction and speed at the time, what kind of weather you’re having. It also depends on how you try to clean it up.”

After the Deepwater explosion, cleanup crews sprayed almost 2 million gallons of a chemical dispersant called Corexit on the surface to break up oil slicks. The oil, though, likely ended on the bottom of the Gulf, and the chemical was still being found in oil on Louisiana beaches months later.

That’s important, Seim said, because there are times when wind direction would push surface oil in to shore, and times when the same wind might push subsurface oil ashore.

Where that oil might come ashore is even more problematic. Seim thinks it would likely end up south of Oregon Inlet if the rigs were north of Cape Hatteras because since water over the continental shelf “generally” moves north to south.

The risk of oil making it to the North Carolina shore after a major spill “is significant,” he said.

Seim also think that drilling 50 miles off the N.C. coast will be technically challenging, especially north of Cape Hatteras. “That’s going to put you in waters 2,000 meters deep, maybe as deep as 3,000,” he said. “Deepwater Horizon was about 1,500 meters. And the Gulf of Mexico is like a bathtub compared to the Atlantic off North Carolina.”

Seim said that until recently, there was little urgency to determine where spilled oil might go in the Atlantic.

“I still don’t think we have a very good sense of that circulation at times,” he said. “And I think there were a lot of people who were surprised at the results of what has been done recently.”

Charles “Pete” Peterson of the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City cited a simple rule to determine the potential for spilled oil reaching N.C. beaches: If you see sargassum on your beach, you could see oil.

Sargassum is a brown algae found in large masses in the Sargasso Sea, a region in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, and in tropical waters around the world. It is distinguished by its brown color and small leaves resembling appendages that allow it to float. A cursory Google search shows that it’s found on virtually all of the state’s beaches at times, especially in the summer, when prevailing winds are south and southwest.

BP Spill as a Yardstick

So what could one reasonably expect if oil entered the Gulf Stream, crossed onto the continental shelf and made it to North Carolina’s estuaries and beaches?

Bob Deans, associate communications director of the Natural Resources Defense Council and author of the book, Deepwater Horizon: The Oil Disaster, Its Aftermath, and Our Future, said one can’t assume any disaster would be as bad as that one. But he said it’s fair to look to Deepwater as a harbinger of the kinds, if not the extent, of damage likely to occur.

“With Deepwater, you had 1,100 miles of shoreline impacted,” he said. “On the East Coast, that’s from Savannah to Boston. If you ask me if it’s worth the risk, I’d ask you to ask someone walking on the beach at Holden Beach or Nags Head if they’d like to see a 25,000-pound tar mat roll upon the beach, like happened 50 miles or so from New Orleans in March, five years after the blow-out.

“I’d suggest that you ask them how they’d like to see dead dolphins, and oil-covered sea birds, and bluefin tuna with birth defects and abnormalities in their hearts. I’d suggest that you ask them how things like these are going to help the tourism industry or the commercial and recreational fishing industries in North Carolina.”

Since the BP blowout, nearly 1,200 dolphins have been found dead in the affected area. Experts estimate that as many as 800,000 seabirds died, including 12 percent of the brown pelican population and 15 percent of the royal terns. Some say 25,000 marine mammals might have died. Hard figures are difficult to obtain.

The National Wildlife Federation, Deans said, reported that strandings of endangered and threatened sea turtles jumped from an average of about 100 per year before the spill to more than 500 a year for several years after the disaster.

“I’d just ask people in North Carolina if they think it’s worth risking these kinds of things for what most say could – could – be a six-month supply of oil, about 3.3 billion barrels,” Deans said.

Peterson is also worried about activities that might disrupt avian and marine life off Cape Hatteras, which is the area in which the Gulf Stream separates from the continental slope to the deep ocean, and where southward-flowing continental shelf water from the Middle Atlantic Bight converges with northward-flowing continental shelf water from the South Atlantic Bight, resulting in an up-welling of nutrient-rich water.

Marine mammals, such as bottle-nosed dolphin, tend to congregate in the area. Sea birds flock there in large numbers at certain times of the year, Peterson said. It’s also where northern marine fish species and southern species overlap, a big reason North Carolina has such rich commercial and recreational fisheries.

Seafood and Oil

It’s difficult to ascertain impacts an oil spill would have on fishing and fish.

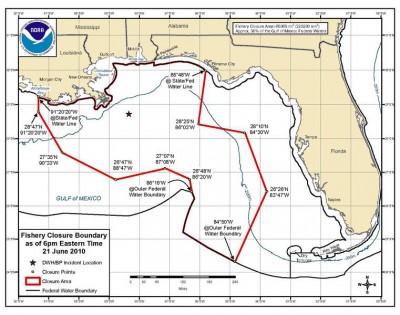

Seafood safety is one issue. On May 3, 2010, less than two weeks after the BP spill, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, closed more than 6,800 square miles of the Gulf of Mexico to commercial and recreational fishing. The closure centered largely between the mouth of the Mississippi River and Pensacola Bay in Florida. By June 2, the area closed to commercial and recreational fishing grew to more than 88,000 square miles, or more than a third of Gulf of Mexico’s federal waters. NOAA started reopening waters a month later.

Generally, according to a NOAA fact sheet, fish are less likely to become contaminated or tainted because they typically are either not exposed or are exposed only briefly to the spilled oil.

The legacy of oil production, though, has plagued some areas of the Gulf Coast well before the BP disaster. For example, Texas health officials, advise against eating speckled trout and red drum caught in Galveston Bay because of PCB contamination. And Louisiana occasionally issues consumer advisories based on the presence of PCBs.

Shellfish are more likely than fish to become contaminated from spilled oil because they are more vulnerable to exposure and less efficient at metabolizing petroleum compounds once exposed. Shellfish are generally less mobile and have more contact with sediments, which can become contaminated and serve as a long-term source of exposure.

Among crustaceans, species that burrow are at the highest risk of exposure at spill sites where bottom sediments are contaminated, followed by species that use nearshore and estuarine benthic habitats, according to NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service.

Bivalves – oysters, clams, scallops – are at the highest risk of contamination because they are filter feeders and live primarily in shallow tidal and intertidal areas that are more likely to become contaminated.

However, just because fish and shellfish are eventually deemed safe to eat, that doesn’t mean their stocks won’t suffer long-term consequences from Deepwater Horizon or another major oil spill.

Disturbing Research

Field and lab studies published in 2013 by Fernando Galvez and others at Louisiana State University found that oil buried in sediments in the shallow waters of the Gulf triggered genetic reactions in the gills and livers of local populations of killifish, a prey for marine species vital to the region’s economy.

Embryos that were exposed to oiled sediments hatched at a rate 40 percent lower than those cultivated in samples from oil-free sites, and those that did hatch were smaller than they should be and had little “vigor.”

Galvez said this month that his team has continued its research primarily in the lab, and the evidence of effects has continued to mount. He also noted that some of his research indicates some organisms have started to develop a tolerance of hydrocarbons, “but we’re trying to tease out what the costs of that tolerance might be. Is there going to be reduced fecundity (reproductive rate)? They do seem to be smaller than the same species in the wild.”

Other research, he said, indicates that the toxicity of oil and its likely effects on fish eggs are increased by ultraviolet light, which of course is a normal condition.

He cautioned, however, that it’s too early to say whether the oil from the Deepwater Horizon disaster will have long-term effects on the stocks of fish in the area. He noted that industry officials have and are likely to continue to cast doubt on research that shows lasting effects on fish, just as they have cast doubt on studies that link dolphin deaths, even now, with Deepwater oil.

“They point out that there are a lot of toxins out there, and that there is no absolute proof,” he said. “Certainly, to a degree, they are correct. But the bottom line is that there isn’t any evidence of anything else, any major event or change, that would have had these impacts.”

Peterson, the UNC scientist, said he was aware of Galvez’ research, but said the findings appeared to apply only to the most heavily oiled marsh. Still, he said, it’s consistent with other research that shows that oil lingers in sediments in marshes for long periods of time, even decades.

Peterson worked for years on the team that studied the Exxon Valdez tanker oil spill in 1989 in Alaska. Despite the BP’s claims that much of the Gulf has returned to normal, he said, there’s plenty of evidence that if oil gets into wetlands – the breeding grounds for shellfish and countless finfish – impacts can linger for up to 20 years, if not more, in sediments, affecting fiddler crabs and the benthic organisms at the bottom of the food chain.

The red tide in North Carolina wiped out most of the state’s prized bay scallops – found in sea grass beds – in 1987, and Peterson and others have said that’s a good part of the reason the fishery has never recovered.

Even after two decades, he said, the crabs studied in Alaska don’t burrow as deeply and don’t display their normal response mechanism when threatened.

Thursday: Pipelines and refineries