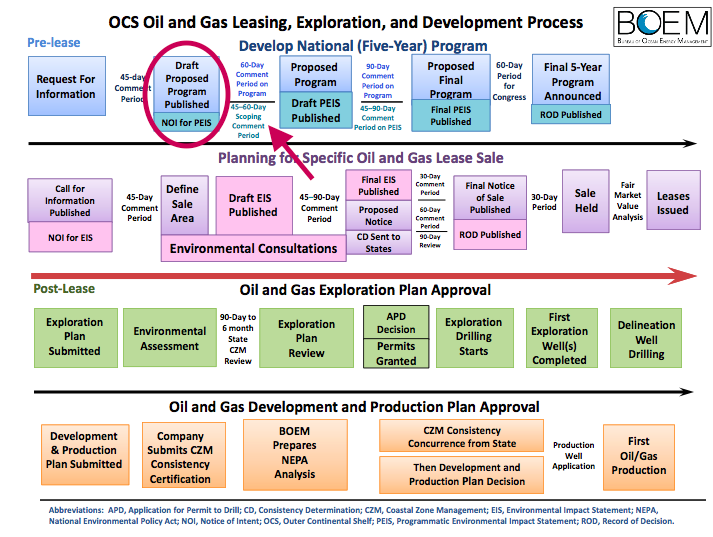

The federal process for permitting offshore drilling is long, tortuous and confusing to those of us in North Carolina who haven’t had to deal with it before. Just look at the flow chart that accompanies this story. Rube Goldberg would be proud.

But take heart. The plans to drill for oil or natural gas off the N.C. coast are at the very beginning of the process. There will be a number of environmental studies and plenty of opportunities for public involvement before production wells – if it ever comes to that – are drilled.

Supporter Spotlight

In areas like the Gulf of Mexico where drilling is common and the infrastructure exists, It takes anywhere from four to 10 years after companies lease the seafloor from the federal government for production to start. In a so-called “frontier area” like the East Coast, where there are no wells currently and no undersea pipelines or other needed infrastructure, it’s anybody’s guess as to how long it would take for oil or natural gas to reach consumers.

Under the draft leasing plan announced by the federal government in January, only one lease is planned in the Atlantic in 2021. Don’t expect, then, to see any oil or natural gas from production wells until the 2030s at the earliest. And that’s barring any lawsuits or permit challenges.

The Process

The process involves a series of well-defined steps that are supposed to protect the interests of the public, the federal government and businesses.

Waters more than three miles from the shoreline and to the end of the continental shelf —about 200 miles — are considered the property of the United States government, legally defined as the country’s exclusive economic zone. Like any property owner who wants to insure their property will be used in a manner consistent with their wishes, the government establishes rules and regulations for its use and offers leases for the development of those resources.

The process for offering leases is spelled out in the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act and follows a proscribed schedule. Congress first passed the law in 1953 and has amended it several times since.

Supporter Spotlight

The law divides the outer continental shelf into four major management areas — Alaska, Pacific, Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic. Lease sales occur in five-year blocks with each area allotted a timeframe in which leases are available for purchase.

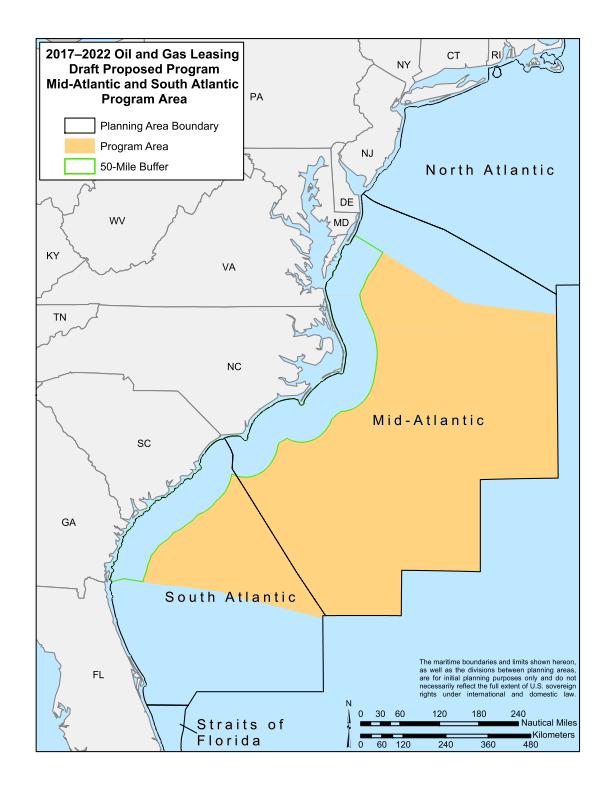

The current program, 2012-2017, includes only the Alaska and Gulf of Mexico management areas. The proposed 2017-2022 lease program that the Obama administration announced earlier this year includes a portion of the Atlantic region from the Chesapeake Bay to the Georgia-Florida line, the western Gulf of Mexico and the north shore of Alaska.

The new lease plan is still in draft form while the federal agency in charge of managing offshore leases, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, prepares an environmental study on the plan.

The next step in the process will be the release sometime next year of a so-called “Proposed Program.” It’s not the final document, although it will contain many of the final elements. There will be public meetings during a 90-day comment period. Then, BOEM will issue a “Proposed Final Program.” Congress will then have 60 days to act on the plan. The “Final Program and the Record of Decision” will follow, probably by the end of next year. Leasing in the Gulf of Mexico would begin in 2017.

The Devil and the Details

Because it is a multi-step process, the BOEM permitting procedure can seem confusing. To know when one phase ends and another begins can be difficult for the public to follow. Adding to the confusion, an environmental-impact statement, or EIS, required by the federal National Environmental Policy Act, runs parallel to and in conjunction with the development of the leasing plan. That process focuses on environmental effects and mitigation strategies and is integrated into the final leasing plan.

It’s important to remember that while they run concurrently, the environmental study and the leasing plan don’t follow the same schedules. As an example, the proposed leasing plan released by BOEM had a 90-day comment period, while the public had 45 days to comment on the EIS. The final EIS will have a 30-day waiting period, allowing for last-minute editing and informational changes that do not alter the content of the study. The leasing plan will reflect the EIS’ conclusions, but Congress will have 60 days to act on it before it becomes final.

Although the processes are integrated and the BOEM can’t develop a leasing plan without an environmental assessment, the two documents address different issues, said Caryl Fagot with BOEM’s public affairs office in the Gulf of Mexico region. She noted in an email that the U.S. secretary of the Interior considers eight factors in determining the size, timing and location of leasing. They include things like the geology and geography of the seafloor, the location of regional and national energy markets and needs, competing uses of the ocean surface and bottom and the interests oil and gas producers.

By comparison, based on information on the BOEM website, the EIS process focuses mainly on environmental and social issues, such as water and air quality, biology, physical oceanography and archaeology.

There is some overlap in the two processes, but there are also areas that are distinct from one another. NEPA permitting does not typically examine “interest of potential oil and gas producer” and BOEM has no provision for looking at undersea archaeological sites.

No Expansions

After the draft leasing plan is issued, the area under consideration can’t be expanded, although areas may be removed from plan. “Proposed areas and sales in the Draft Proposed Program can be deleted but not added,” Fagot wrote.

Enlarging the lease plan’s footprint would require restarting the entire process, BOEM officials say.

Expanding to proposed leasing plan for the Atlantic is particularly relevant because Gov. Pat McCrory is urging BOEM to move the current 50-mile buffer in the plan closer to shore.

If the leasing plan moves forward as presented, the sale of one lease in the Atlantic won’t take place until 2021. It is important to remember, the sale of a lease does not give the leaseholder permission to drill — only the right to submit a plan to drill, with another set of permits to be filed.

The permitting process for drilling for oil can be very lengthy, according to Fagot. “Even after the sale of a lease, there is a permitting process for exploration or drilling for resources,” she writes. “Many steps must be taken . . . and the time frame varies greatly depending on the lease location, water-depth, lease stipulations, availability of equipment, company priorities and the level of analysis and approvals needed at each step. It could take a year to 10 years.”

A drilling permit is a two-step process that introduces a new player in the permit mix: the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, or BSEE. Created in response to what was seen as lax oversight following the BP Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010, the BSEE has more autonomy to enforce regulations than regulators had under the Minerals Management Service, the predecessor to BOEM.

The first permit is for an exploratory well with BOEM and BSEE issuing permits. Another EIS will be done and the state must certify that the drilling is consistent with its coastal-management program. If the company thinks the site has potential, a Development and Production Plan is created that will allow for a production well to be drilled. Again, another EIS and another consistency review. If BOEM signs off on the NEPA review and the state finds the use of the site consistent with its guidelines, the plan is submitted to BSEE who must approve the production well application.