Last of two parts.

NAGS HEAD — Efforts to tame Oregon Inlet began in earnest a half century ago, when watermen started having problems navigating through sand-choked channels. Legislation was introduced, projects were proposed, studies multiplied like barnacles and maintenance budgets were steadily slashed. Today, inlet conditions have been worse than ever – although the inlet is currently open – but state and county officials have ambitious plans for a long-term solution.

Supporter Spotlight

While the state is trying to find ways to acquire the inlet from the federal government, a proactive regular dredging program is being pursued.

“Nobody can definitively say that this will work until we try,” Harry Schiffman, vice-chairman of the county Oregon Inlet Task Force, said of the proactive approach. “But it’s the only option that everybody can get behind.

“If the state gets control of that land,” he added, “then that would change.”

The appropriations bill passed by the N.C. General Assembly last year authorized state Department of Administration Secretary Bill Daughtridge to negotiate terms of an acquisition agreement with the landowner of Oregon Inlet, which is the U.S. Department of the Interior. If the property is acquired, the state Department of Environment and Natural Resources would have the authority to add Oregon Inlet State Park to the state parks system.

The bill also requires the state Department of Administration, or DOA, on July 1 to start condemning federal property that is “necessary to manage existing and future transportation corridors on the Outer Banks.”

Supporter Spotlight

What that legislation did not do is provide funding, and it appears doubtful that the department will meet the mandates.

“The Department of Administration is in conversation with the federal government with regard to Oregon Inlet and the surrounding federally owned property,” agency spokesman Christopher Mears said in an e-mail. “We are discussing all options listed in the 2014 Oregon Inlet Acquisition Task Force Report.”

Jordan Hennessy, a legislative aide for state Sen. Bill Cook, a Beaufort County Republican, said that a new bill, SB 160, will be introduced soon that would pay for the unfunded costs. It would provide $1 million to the DOA for attorney fees and preparation required to meet the legislative deadlines. The proposed bill also would reimburse DOA $150,000 for costs associated with exploring acquisition, including surveys, appraisals, legal research and sand management studies, and would increase the appropriation to the state Shallow Draft Inlet Fund by $1.7 million.

Hennessy said that a line item in the bill would appropriate about $4 million for intermediate dredging at Oregon Inlet. He added that the bill is likely to pass the Senate within weeks, and he expects that it will be supported in the House.

Rep. Paul Tine, I-Dare, did not respond to a request for comment on the proposed legislation.

In its 27-page report to the General Assembly last May, the Oregon Inlet Acquisition Task Force, an ad-hoc study panel created in 2013, recommended that the state:

- Acquire necessary easements to develop effective and environmentally sound engineered solutions to maintain stability of the inlet.

- Continue legal research into property titles north and south of the inlet.

- Assess whether various engineered alternatives are feasible in addressing navigation issues in the inlet.

- Conduct a larval transport study to determine impact on fisheries.

- Advance the chosen project timeline and facilitate permitting.

“The situation involving the inlet has reached a critical point,” the report concluded. “Human safety, economy viability and environmental safeguards can all be enhanced. But taking no action is no longer an acceptable option.”

It wasn’t long after the Bonner Bridge was built in 1963 that watermen and local government officials began lobbying for construction of twin jetties that would theoretically stabilize the inlet by blocking sand traveling along the shoreline from entering the inlet. In 1970, Congress finally approved the $108 million jetty project, but failed to provide construction funds.

For the next 33 years, lobbying by the watermen – some of them the same people – continued unabated. The U.S. Department of the Interior and environmental groups, however, opposed the rock walls, saying that they would harm fisheries and property within Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, as well as erode beaches south of the inlet.

Jetty proponents said that in addition to creating jobs and tourism income, a stable, open inlet also promotes flushing that maintains water quality in the surrounding estuarine waters and allows a safe outlet for storm-driven surges.

Finally, in 2002, the White House Council on Environmental Quality announced that the jetty project was not warranted. Instead, the federal government promised to do more extensive dredging – a promise that Dare County and the state claim has not been kept.

But the rebuff by the council inspired renewed talk of getting state control of the inlet so the state could move ahead with an engineered project. It wasn’t until the task force was established in 2013 to study acquisition of the inlet that any action was taken. With advancements in science and technology, according to the report, a combined sand bypass-jetty system could address the shoaling problem in the inlet without negative effects on the beaches and fisheries.

In this video shot in Wanchese, locals describe the effects that an unruly Oregon Inlet is having the economy and the livelihoods of fishermen.

David Hallac, superintendent of the National Park Service Outer Banks Group, which owns the submerged land and portions of the shoreline of Oregon Inlet, said that there has been no contact from the state about potential acquisition.

“I’ve never had a single request from anyone in the state of North Carolina to even discuss the issue,” he said last week.

But Mike Bryant, manager of Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, which owns the land on the northern tip of Hatteras Island on the inlet’s south side, said that about one month ago, he attended a meeting in Atlanta with DOA leaders to discuss Oregon Inlet.

“It was just a conversation,” he said. “There were no commitments. They were information-seeking.”

As far as he knows, Bryant said, no specific proposal of a land deal has been submitted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service regional office. The service owns the wildlife refuge.

“It’s a state initiative,” he said, “and we’re waiting for it to be fleshed out in order to give a proper response.”

In the task force report, it was stated that in preliminary discussions, Fish and Wildlife officials expressed interest in potential land trades that could link pieces of federal property.

If a proposal is made, Bryant would issue a compatibility determination, which would then be sent to the regional office to concur, or not.

The report cited a market value appraisal of about $30 million for the 710 acres that the state would be interested in acquiring on either side of the inlet.

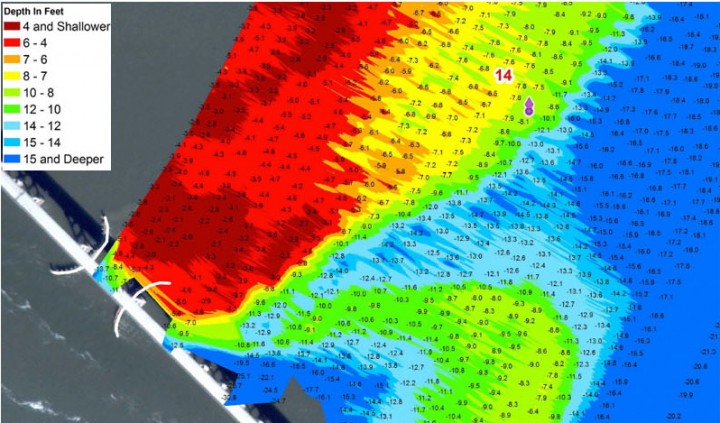

Meanwhile, Dare County is working feverishly to find the $3.5 million it needs to match state funds for the annual dredging budget. In the proposed agreement between the state, the Army Corps of Engineers and the county, the inlet could be dredged by the Corps for 12 hours a day for 340 days a year for about $7.3 million.

Federal allocations for dredging have shriveled in recent years. Of an estimated 1,000 federally authorized dredging projects across the nation, 700 received zero funds. Oregon Inlet did receive $900,000 in federal dollars last year, but it was only enough to cover surveying. A previous agreement between the state and the Corps provided for some dredging in the inlet this year to protect the Bonner Bridge, and Congress was able to move funds around to provide costs for some additional dredging.

Initially, Dare County proposed to borrow from its countywide beach re-nourishment fund that is fed by a 2 percent occupancy tax and shared by the county’s towns and the tourism bureau. But after a furious backlash, the county promised to use only its share of the fund to put toward dredging. Another potential fund source, a ¼-cent sales tax, was killed off almost instantly by the state legislature.

A follow-up proposed by Dare County Commissioner Warren Judge to use funds from a repealed 1-cent sales tax collected previously for beach re-nourishment — an idea the board agreed to pursue — would be illegal, according to Hennessy, because the purpose of a tax cannot be changed after the fact.

While the county continues looking under the cushions for stray funds, a family feud has broken out between its Oregon Inlet Task Force and the Oregon Inlet and Waterways Commission over a proposal to merge the panels. Hatteras Island residents are insisting that the money and focus include Hatteras Inlet, which has its own navigation problems. Others believe the focus has to stay on Oregon Inlet to prevent confusion.

The elephant in the room, the aged and deteriorating Herbert C. Bonner Bridge that everyone has to navigate under or drive over, still cannot be replaced until a lawsuit is resolved. A new bridge is designed to allow for safer boat passage, at least until the wild inlet rules otherwise.