RALEIGH — The state House, in a hurry to send as many bills through the crossover threshold before yesterday’s deadline, approved a bill Wednesday that critics and some legislators say will ultimately gut a 40-year-old law that requires environmental review of state projects.

The bill now goes to the state Senate.

Supporter Spotlight

During a marathon session that started midafternoon Wednesday and ended at around 2:30 a.m. yesterday, House leaders also used a procedural move to ensure that another bill, with several key environmental provisions, also made it through the crossover deadline. That bill, the Regulatory Reform Act of 2015, includes controversial provisions related to streamside buffers and hog farm waste. A final House vote on the bill is scheduled for May 5.

Sponsored by Rep. John Torbett, R-Gaston, the bill changing the State Environmental Policy Act, or SEPA, emerged in committee last week and moved quickly to the already packed House calendar ahead of the critical April 30 crossover deadline. To remain viable for the rest of the session, bills that are not budget or elections related must be approved by at least one legislative chamber by the deadline.

At the SEPA bill’s only hearing before the House Regulatory Reform Committee and again on the House floor late Wednesday, Torbett said SEPA had outlived its usefulness since its passage 44 years ago.

“A lot of things have changed since 1971 obviously,” he said Wednesday night.

North Carolina’s environmental review is the strictest among Southeast states, he said. “Any amount of expenditure of public funds can trigger a SEPA,” Torbett noted.

Supporter Spotlight

He said it has been 10 years since the last revision.

“At one time it was the right thing to do for North Carolina,” he said. “But now it’s more of a redundancy.”

Rep. Chris Millis, R-Pender, who co-sponsored the legislation, said the bill would eliminate an unnecessary and costly “boondoggle” required to spend public dollars. He said the state had enough other environmental protections in place and no longer needed the strict SEPA standards.

But bill opponents, including a handful of Republicans, urged a vote against the bill.

In debate on the House floor Wednesday night, Rep. Rick Catlin, R-New Hanover, and Rep. Pricey Harrison, D-Guilford, both succeeded in passing amendments mitigating the sweeping nature of Torbett’s bill, which would have limited projects that trigger the SEPA process to those costing at least $20 million in public money and involving more than 20 acres.

Opponents have noted that few projects would meet those thresholds.

Catlin said he’s heard concerns from constituents about the $20 million threshold and said he believes it would cut the program “too much, too fast.”

His successful amendment lowers the threshold to $10 million.

Harrison’s amendment lowers the proposed acreage threshold to five and ensures that there would be a SEPA review for projects involving state parks.

“It’s not duplicative,” she said of SEPA. “It actually provides a broader review when a project is proposed and it also gives an opportunity for the public to have input.”

Rep. Chuck McGrady, R-Henderson, said he did not think the fight over the bill was necessary. “Why SEPA is such a sacred cow for both sides of this debate I have yet to discern,” he said.

McGrady said SEPA is not the top environmental protection the state has but has important functions. The bill’s proponents, he said, were using the high thresholds to kill any review.

“This bill has been called a reform and I really think it’s more in the nature of a repeal,” McGrady said.

SEPA’s most important function, he said, is to allow public review of projects, especially in the case of projects that come up quickly.

“A few of you were here when the Titan cement issue came up and what was the law that slowed that thing down so someone could figure it out? It was SEPA,” he said.

Questions traveling to the Senate

The SEPA program is coordinated out the N.C. Department of Administration. Each department in state government has adopted a set of criteria for triggering a SEPA review. The criteria determines was is a “significant environmental impact” under the law.

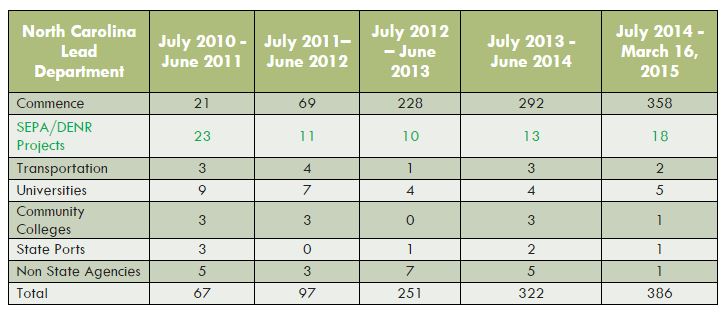

Interestingly, the state’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources, or DENR, is not the most active participant in SEPA. The top department triggering such reviews in recent years is the N.C. Department of Commerce, the result of the state’s booming solar industry. Under criteria set by the State Utilities Commission, solar projects over 2 megawatts in size require a SEPA review. Of the department’s 358 SEPA projects in the past year almost 281 were solar projects, or about 79 percent.

SEPA involves a two-step process that first determines if the effects of projects are significant enough to require comprehensive studies.

Under current law, the state doesn’t use specific size or dollar thresholds to determine if a project should have a thorough review, but instead has relied on interpretations of what constitutes “significant environmental effects.”

One major question about Torbett’s bill is what effect switching to cost and size thresholds will have in triggering SEPA.

Lyn Hardison, SEPA coordinator for DENR, said as the bill has progressed, it has been hard for the department to determine just how many projects will fall under the proposed thresholds. The department, she said, hasn’t collected information on the costs of projects.

“We can’t say how many would be affected because we don’t have those numbers,” Hardison said in an interview last week. She said setting a dollar figure has not been used because it could have unintended consequences.

“You could have a project fall below the dollar amount that might cause significant adverse environmental damage. Also, you could have a project that was over the dollar amount, with little or no impact and be required to prepare a SEPA document,” Hardison said. “And you could have economic projects that have little to no construction involved that could easily be over the dollar amount, preparing SEPA documents.”

Ron Sutherland, a conservation scientist with Wildlands Network, said there are two main problems with the legislature’s approach.

Beyond setting dollar and acreage thresholds and abandoning the use of “significant environmental impacts,” the bill also requires that projects’ direct environment effect be assessed, he noted. Current law requires that cumulative and indirect effects also be studied.

“That’s a wrong-headed approach,” Sutherland said. “You have to be able to look at the big picture.”

He said a review wouldn’t be able to consider how a series of projects might affect a watershed, but would have to just look at each one individually.

Sutherland, who was a plaintiff in a lawsuit against N.C. State University to require a SEPA review for the sale of Hoffmann Forest, said that the new law could clear the way for sales of public lands without adequate public review.

Mary Maclean Asbill, an attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center, said while the debate has focused on thresholds, SEPA’s role in public review should also be taken into consideration as the bill moves through the N.C. Senate.

“Lost in this debate is the importance of public input, in having taxpayers know how their money is being spent,” she said.

She said all sorts of projects like landfills, municipal infrastructure and inter-basin transfer projects could avoid public review and input under the proposed bill.

“We don’t want to see the public eliminated from the process,” she said.

The SEPA review, she said, shouldn’t be confused with the environmental review required by the National Environmental Policy Act, a federal law known as NEPA. Projects that required federal permits are required to undergo such reviews.

An official with the N.C. Chamber of Commerce got the two confused, Asbill said, in a recent op-ed in the News & Observer of Raleigh. He singled out the fight over the Herbert C. Bonner Bridge in Dare County as a reason to get rid of the SEPA program.

All of the law center’s highway related lawsuits, including Bonner Bridge, have been filed under NEPA, she said.