Second of three parts.

Saltwater is creeping farther inland into the soil and surface waters of North Carolina’s coastal plain. This “saltwater intrusion,” as scientists call it, has an ability to transform freshwater landscapes long before they’re permanently drowned by the rising sea.

Supporter Spotlight

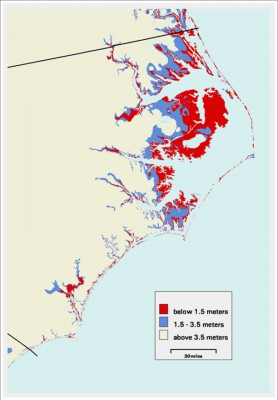

Pine trees are dying along the edges of the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds. Forest lines are retreating; marshes are replacing forested wetlands; agricultural crops are having trouble growing; and the foundation of the land — its peat soil — is disintegrating, lowering an elevation that is only two feet or less above sea level on average.

Five researchers from four state universities are investigating the future risks of saltwater intrusion in the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula, a region reliant on its farming. Nature, they say, won’t be the only agent of change. They’re also investigating how the area’s residents will play a role in conserving their natural resources, or not.

There are a few reasons why saltwater is moving into areas that have never dealt with it before, say the researchers. First, there is the general rise of the sea level. On land as flat as this peninsula’s, any increase in sea level will bring the salty tides farther inland. Then, there are the surges from coastal storms that flood the land with seawater. Then, drought factors in, too. When rainfall is sparse, the concentration of salt in brackish waters increases. And according to Mac Gibbs, the former director for the Hyde County Center of the N.C. Cooperative Extension Service for 25 years, the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula has experienced less than average rainfall over the last five years.

Climate change models, referenced in numerous published research papers, suggest that the severity and length of droughts and the frequency and intensity of hurricane storms in the region will increase. Both of which will likely increase the frequency and severity of saltwater intrusion.

But, saltwater intrusion isn’t only related to flooding and drought, says Ryan Emanuel, an N.C. State University professor in the Forestry and Environmental Resources Department who specializes in watershed hydrology. It’s also affected by the natural and artificial drainage across an area. What makes the Albemarle-Pamlico region particularly prone to the effects of saltwater intrusion is its extensive, manmade network of ditches and canals. What the farmers use to drain freshwater from their crop fields is also the pathway for saltwater from the sounds and creeks to work its way back into the interior of the peninsula, Emanuel notes.

Supporter Spotlight

“It’s important to start a discussion on the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula today,” he says, “if residents, landowners and others want to get out in front of these issues and determine what long-term strategies might be best for dealing with and adapting to climate change.

“The big question,” Emanuel says, “is how do we respond to [the] change? Is it business as usual as long as possible? Or, are there proactive decisions that can be made in the coming years and decades that can maintain quality of life in the region’s communities and conserve its natural resources for future generations?”

A native of eastern North Carolina, Emanuel is joined by four other researchers and several students in leading a $1.5 million dollar research project in the Albemarle-Pamlico region funded by the National Science Foundation. The team combines various fields of study: biochemistry, regional planning, hydrology and ecology.

Over the next five years the researchers will be collecting data and collaborating with locals and others that have a stake in the outcome of the area, such as land managers and commercial farmers. In the end, they’ll create maps that can project how saltwater intrusion will affect the region – over 4,300 square miles, more than three-and-a-half times the size of Yosemite National Park — at different points and time. Unlike other vulnerability maps though, these will take into consideration both different scenarios of climate change and people’s land use.

Will someone build a seawall or a levee to keep saltwater off his land? How then will that diverted water affect his neighbor’s property? These maps will be able to project those answers for land managers and others. The researchers call the maps “SIVI,” for “saltwater vulnerability index.”

“Can we build an index that is powerful enough to assess salinization accurately for the study region, yet flexible enough to be adapted to other regions? That is going to be a challenge,” said Emanuel.

Todd Bendor, one of the principal investigators, is an assistant professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. He says, “[The project] is about trying to help people understand where the risks are going to be in the future and then, once we understand those risks, we can do something about it.”

“The assumption,” Bendor says, “is that we’re all at the behest of rising sea level, but there’s a lot of things from an engineering perspective and a land management perspective that we can do that curtails it.”

His role in the research project is to talk with people about how they might react to saltier landscapes, or at least what they say they’d do in different scenarios. “It matters how people are willing to adapt or willing to fight against what may be kind of a permanent change in the landscape,” he says.

The Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula can expect more saltwater intrusion, he says. “This is going to happen. So it’s not an ‘if,’ necessarily; it’s just a ‘when.’”

Budgeting for future action is something, he says, that is uncharted territory for land managers, homeowners and farmers. “People are changing the landscape, and I think that it’s not just sea level is going to rise and we’re all going to move inland; it’s in the meantime, there’s going to be a lot of people fighting it, and there’s going to be a lot of people that are going to change their management activities,” Bendor says.

How Bendor will find folks to talk to, how he actually talks to them and how he frames the problem will all be important for the research, he says.

As far as predicting the timing and the consequences of these changes to the land, well, that’s another big chuck of the research project. Three scientists, from East Carolina University and Duke University, are spearheading this part of the project.

Thursday: How increasing saltwater intrusion in North Carolina will affect trees, soil nutrients, water quality and climate-altering greenhouse gasses.